Activities

Bronisław Piłsudski’s Activities in Spisz and Orawa

Activities

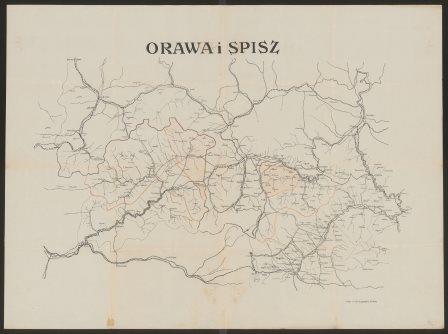

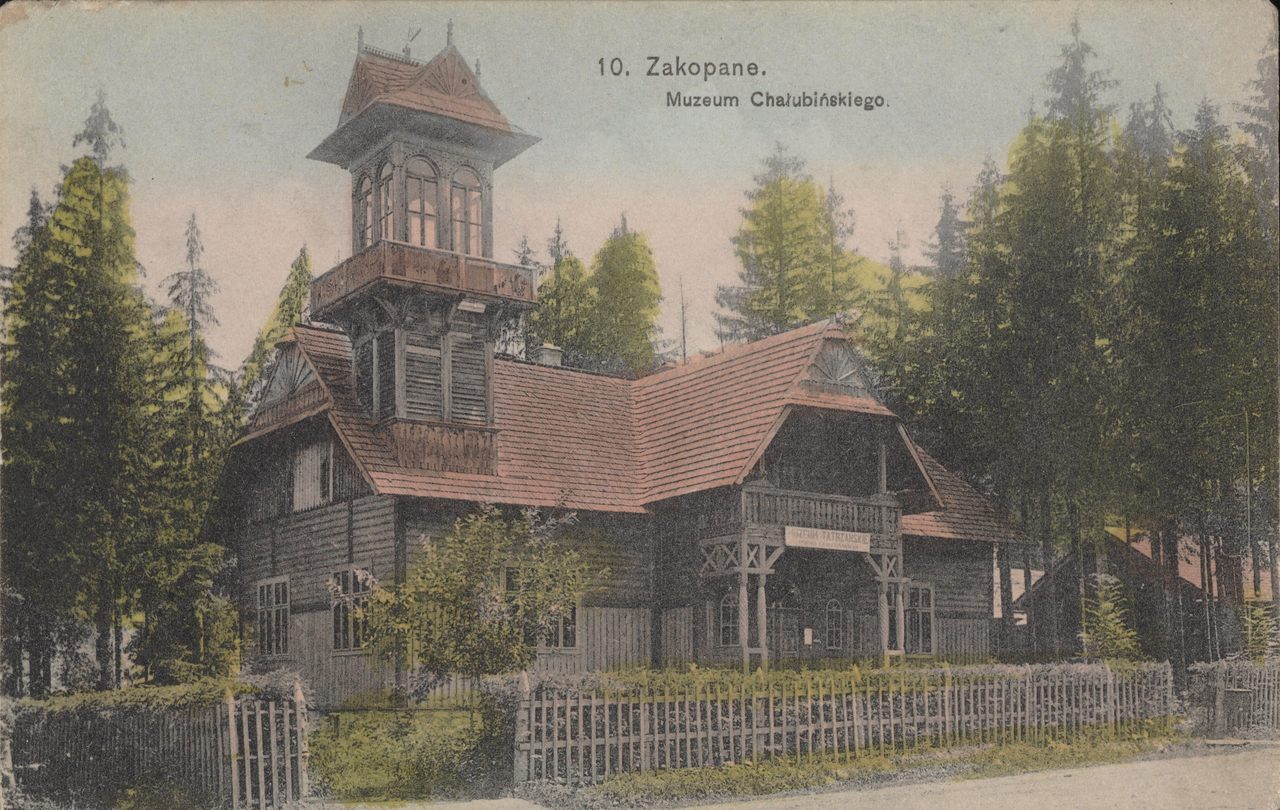

As the head of the Folklore Study Section of the Tatra Museum Society, Bronisław Piłsudski was involved in the organization and promotion of regional research. His area of interest covered not only Podhale, but also Spisz and Orawa. The latter two regions were repeatedly incorporated or detached from Poland throughout history, and at that time, they were a part of Hungary. During his research on the highlanders, the ethnographer became involved in the cause of raising national awareness among the people who lived there.

In large cities, Hungarization proceeded rapidly, while rural areas were virtually cut off from the influence of Hungarian administration and the benefits of assimilation. Language and customs linked the local population to the Beskid or Podhale highlanders, which is why in censuses they were considered ethnic Poles. In 1880, the box showing Polish nationality was removed and replaced with one for Slovak nationality. This was an attempt to prevent the expected influence on the increase of national consciousness from the areas of present-day Małopolska. Paradoxically, this activated Galicia’s public opinion which until then had not raised the issue of the so-called “southern borderlands.”

In response to the denationalization policies of the Austro-Hungarian government, a Polish national-educational campaign was launched in Spisz and Orawa at the turn of the 20th century. Its goal was to cause Budapest to recognize the Polish national minority in Upper Hungary and to grant it the rights enjoyed by other nations within the Empire. It also called for the establishment of Polish schools and a seminary which would have prevented the propaganda carried out by Slovak priests. Efforts to awaken the national awareness were taken up by the Slavophiles brought together by the “Świat Słowiański” magazine and activists from Nowy Targ who collaborated with Bronisław Piłsudski. The tasks they set for themselves included convincing educated individuals about the idea of Polishness through personal influence, bringing together Spisz and Orawa youth in Polish schools, establishing social relations between the inhabitants of Podhale, Spisz, and Orawa, and sending out Polish newspapers and magazines. Earlier contacts with the inhabitants of the borderlands were limited to trade and meetings during pilgrimages to places of worship (the shrines in Kalwaria Zebrzydowska and Ludźmierz were particularly popular).

During his stay in Zakopane, Piłsudski met Dr. Jan Bednarski, a physician who developed political and social activism in Nowy Targ (for which he received the title of the city’s honorary citizen). Born in Bystra near Jordanów, he had the opportunity to come into contact with the borderland population very early in his life. After arriving in the district’s capital, he initiated contacts with the slowly emerging part of Orawa’s intelligentsia that shared a pro-Polish sentiment. Through the illegal delivery of Polish books and newspapers to Spisz and Orawa, he encouraged the local people to learn the literary language. He also played an important role in the dispute over the Morskie Oko Lake, which had continued since the early 19th century. He had an excellent understanding of the problems faced by young people going to school outside their place of residence, as he himself went to the gymnasium at St. Anne’s Church in Kraków which offered extremely modest living conditions. Therefore, as a member of the Diet of Galicia and Lodomeria, he sought to establish a secondary school in Nowy Targ. This objective was finally achieved: in September 1904, the youth of southern Galicia gained the possibility to benefit from secondary education. In his inaugural speech, Bednarski emphasized the institution’s role as a center for shaping national awareness.

After the launch of the gymnasium, the problem of accommodation for students from outside Nowy Targ arose. In early December 1904, the St. Stanislaus Kostka Gymnasium Dormitory Society was organized to raise funds for the construction of a dormitory and supporting poor students. The society bore the total living costs for students from Spisz and Orawa. Bednarski took special care of the region’s youth by paying for their living expenses, tutoring, clothing, and school books.

The activist was one of the initiators of the First Congress of Podhalan Highlanders. At the next Congress held in the summer of 1912, Bednarski saw an opportunity to popularize the Spisz and Orawa issue. Podhale regionalists agreed to be involved in the awareness campaign in Upper Hungary and there was a call for the creation of a periodical to provide information on these topics also to neighbors across the southern border. On 3 August, a specially established Spisz and Orawa Section met to discuss the goals and directions of the activities set by the promoters of Polish identity among the partially Slovakized highlander population. The meeting resulted in the creation of the “Gazeta Podhalańska” daily, which was attractive not only to the intelligentsia involved in the region’s affairs, but also to the locals, since it published readers’ letters written in the local dialect. It was not limited to local issues, as it covered current events taking place in the partitioned Poland and abroad.

Assistance to Spisz and Orawa, mainly in the field of education, was also organized by local units of the Folk School Society. The most active unit was the one founded in Zakopane in 1894. In order to better coordinate the activities of various groups interested in the same topic, Zakopane regionalists proposed the formation of the Spisz and Orawa Committee. This topic was discussed at the General Convention of the Society’s District Association groups in April 1914. Among the guests of the Convention were Jan Bednarski and Bronisław Piłsudski.

Piłsudski’s interests as a researcher were not limited to the Polish region around the Tatras. During his numerous mountain hikes, he came into contact with the people of Spisz and Orawa. While supplementing the Tatra Museum’s collection, he also acquired items from various areas of Upper Hungary. It was his intention that the “Rocznik Podhalański” (conceived as a periodical of the Tatra Museum, but also of other institutions working for the benefit of Zakopane and the surrounding area) was also to be devoted to the Spisz and Orawa issues, which were of interest to Bolesław Wysłouch, the editor-in-chief of the “Kurier Lwowski” daily.

While traveling in Europe, Piłsudski worked for the “Kurier Lwowski” as a foreign correspondent. In one of his letters, he informed Wysłouch that he intended to describe the Polish exhibits in the museums in Paris. While abroad, he visited numerous ethnographic museums not only in Paris, but also in Vienna and Prague. At the time, he wrote scientific chronicles and sent them to the editor for approval. Piłsudski’s interests still included the affairs of the Far East, mainly Japan, where he was warmly welcomed by the local intelligentsia. However, the readers of “Kurier Lwowski” did not seem to like it.

As members of the Folklore Study Section of the Tatra Museum Society, both men also worked together to organize the Ethnographic Exhibition in Lviv. They unsuccessfully tried to gain the support for the idea among members of the Polish Diaspora in Paris. Despite the support declared by quite a large number of people (including Stefan Żeromski and Władysław Mickiewicz), as well as the formation of the Spisz and Orawa Committee, the exhibition ultimately failed to materialize.

In 1911, the Union of Friends of the Polish Tatra People was founded in Lviv; despite its misleading name that suggested an interest in the affairs of the Tatra highlanders, it aimed to carry out comprehensive activities among the people living in the territory of Upper Hungary. The

Union’s program included a number of educational campaigns, together with the creation of Polish reading rooms and folk houses in Spisz and Orawa, and the transfer of “borderland” youth to Galicia for education which was to result in the formation of a new generation of nationally aware Polish intelligentsia. In one of his letters to Wysłouch, Bronisław Piłsudski pointed out the possible negative consequences of going to schools outside the place of one’s residence. He wrote, “There are a few students from Spisz at the gymnasium in Nowy Targ; however, in my opinion, this is a risky thing, because later they try to escape from their sad neighborhood to a more culturally rich center.” To prevent this, a condition for granting educational support was to be that the grantee returned to his or her hometown.

Another demand of the Union’s program was to take steps toward establishing a Polish bishopric in Hungary. The Catholic population of Spisz and Orawa was being Slovakized because of the Slovak-speaking priests serving in the area. The Union also sought to establish cooperation with various organizations that could support it in its activities.

Bronisław Piłsudski wrote to the Union’s board, declaring the Folklore Study Section’s readiness to cooperate. In the letter, he stressed his interest and concern for the “neglected areas” of Spisz and Orawa, and expressed his desire to organize joint scientific excursions of the two associations. In the attachment to the letter, he listed fourteen people applying to become members of the Union, along with a note about the 28 krone of registration fees collected. In another letter – to Bolesław Wysłouch – he noted, “If there are two institutions, it may not be a problem, as long as there is no petty fighting against each other; competition is good, but rivalry combined with resentment is bad.” He also wrote, “I’m not sending money for now, because it might be better to leave it here and organize a branch of the Union, because direct activity here would probably be greater. Zakopane is visited in considerable numbers by both residents of Spisz who want to see a doctor and those selling dairy products.”

All in all, the materials preserved in the National Archives in Kraków do not show that the Union’s activities advocated in the program found any major response from the public. They were limited to distribution of publications in Polish and creation of libraries together with the Folk School Society.

Based on:

K. Zięba, “Bronisław Piłsudski’s Activities for the People of Spisz and Orawa; on the margin of the letter to Bolesław Wysłouch,” “Krakowski Rocznik Archiwalny 2021”, vol. 27, pp. 107-133