Museology

Zakopane

Activities

Bronisław Piłsudski’s ties to Zakopane, where he began his research on the culture of the highlanders, date back to 1908. He gathered a collection characterizing the culture of the Podhale region for the Ethnographic Museum in St. Petersburg.

His second stay in Zakopane began in September 1911. Piłsudski visited the grand Podhale landowner, Count Władysław Zamoyski, who was the vice-president of the Tatra Museum Society. Until April of the following year, he lived in Kuźnice, in the guest room of the Women’s Home Labor School, which was run by Zamoyski’s mother Jadwiga and his sister Maria. In a conversation with Count Zamoyski, Bronisław suggested forming a team to survey the local area.

Years later, Juliusz Zborowski, the first long-time director of the Tatra Museum, recalled:, “Penniless and sometimes suffering acute poverty, Bronisław Piłsudski gathers several settled newcomers around him and collects competently pennies from the wealthy and less wealthy.”

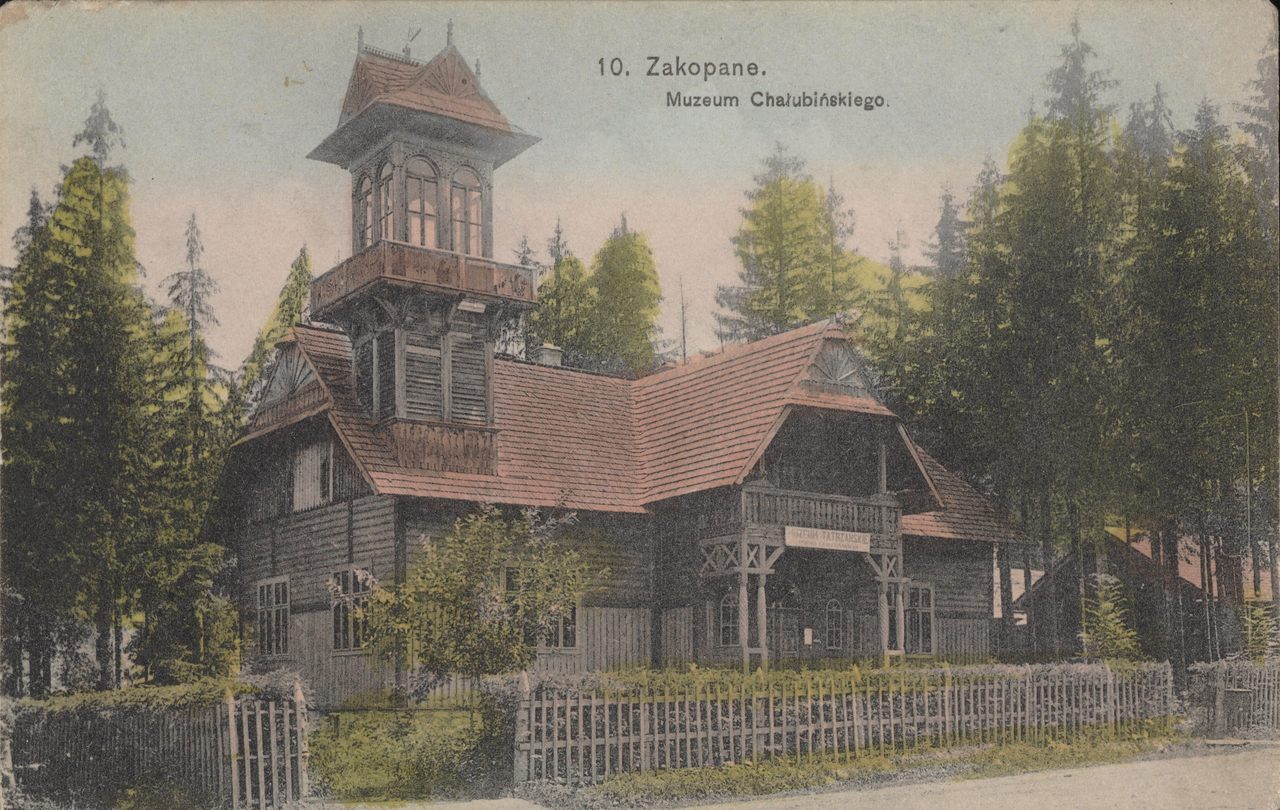

Adam Uziębło, who met Piłsudski at that time, later described the impression Piłsudski made on him as follows, “And finally a new man appeared, a man indeed with ethnographic training, who had already made a name for him, a name very well known by the way. He was Bronisław Piłsudski, the King of the Ainus – the almost authentic ‘King,’ a real scholar. […] There was something immensely attractive about this gentleman with slightly gray hair, neatly dressed, with a small trimmed beard. Wherever he appeared, it was as if he was at his own home. A man he met for the first time was already close to him. There was not a trace of any sentimental exuberance in him. No, Mr. Bronisław did not talk much about himself, did not confide or impose his persona. But somehow it happened that after a few minutes of conversation he would already know who he was dealing with. He would already know what this new acquaintance could do, what he was interested in. And after just a while, he would ask for some clarification or perhaps advice on how to arrange this or that, and how to help someone in his taks; how to get to a place. Soon the topic of the conversation was buckles, wrought-iron belts, shelves for hanging spoons, glass paintings, and roadside sculptures of saints, pots and door frames. And somehow these conversations naturally led to the conclusion that the issue of historical artifacts is very urgent, that they need to be collected most carefully.”

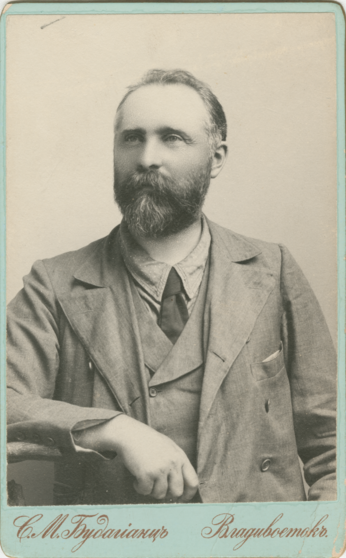

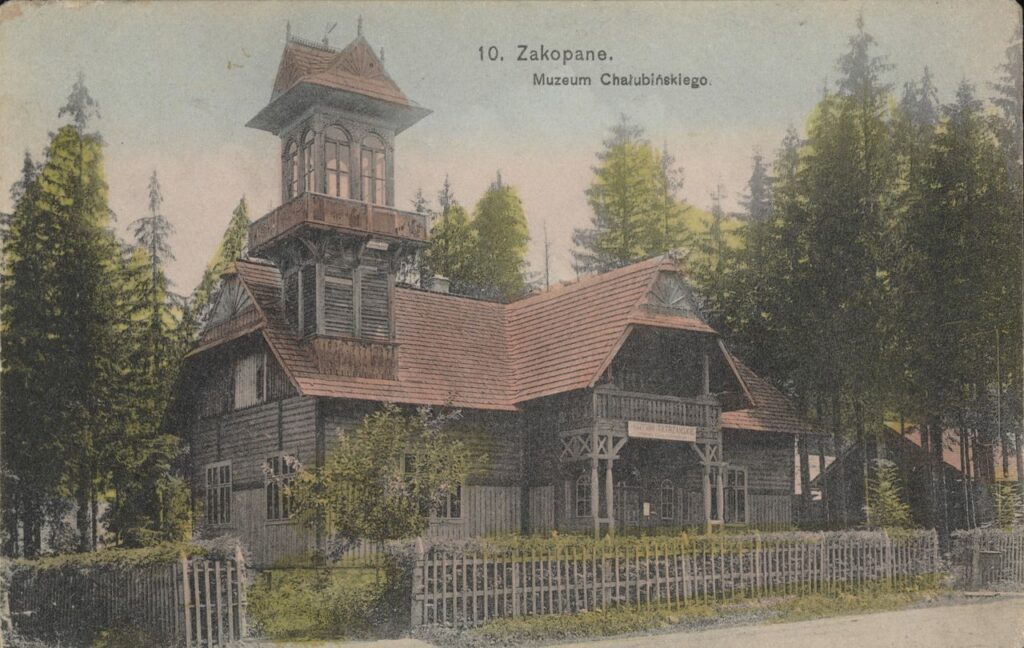

At Piłsudski’s initiative, a team of the Folklore Study Section of the Tatra Society was formed to study the area. The initiator became its head who organized research on the folklore Podhale. Besides the Tatra highlanders, he was also interested in the people of the Orawa and Spisz regions which were a part of the Hungarian territory. In Zakopane, Piłsudski met a distant relative, Stanisław Witkiewicz. It was mainly under his influence that Bronisław started his research on highlanders. Bronisław pushed for the construction of a new building for the Tatra Museum which would be suitable for collecting exhibits and creating exhibitions. The established in 1888 museum was at the time housed in a private building with the library and conference room in another location. It was Stanisław Witkiewicz who worked on the design guidelines for the new building and the ethnographic exhibition. This well-known painter, writer, architect, and creator of the so-called Zakopane style, oversaw the construction, for which the cornerstone was laid on 3 August 1913. Piłsudski was unable to attend the ceremony, as he was in Brussels at that time. A sizable financial contribution to the construction of the new building was made by the aforementioned Zamoyski. The construction works were completed more than 10 years after the decision to build the museum in 1922, which was after Piłsudski’s death. The museum houses 170 artifacts collected by Piłsudski in 1912 and 1913.

When Piłsudski appealed to highlanders to offer items for the museum, many of them were willing to do it. Some did it out of snobbery, others out of respect for him. Zborowski recalled, “Piłsudski had a unique gift of extracting old ‘grandfather’s stuff,’ i.e. things no longer in use, free of charge.” The contributors received free admission to the museum for life. While conducting research on the Polish highlanders, Piłsudski tried to awaken in them a readiness to join the Polish community as soon as the homeland regained its independence. He believed that the Folklore Study Section of the Tatra Museum had a huge role to play in this area.

In the second decade of April 1912, Piłsudski moved to a villa owned by a physician, Tadeusz Korniłowicz, in Bystre, which was then a small village halfway between Zakopane and Kuźnice. Korniłowicz was Bronisław’s friend and a member of the Folklore Study Section of the Tatra Society. After 18 years, Piłsudski’s wax cylinders were discovered in the attic of this villa known as Korniłowiczówka. On the wall of the room where he lived, there was a portrait painted by Adomas Varnas, one of the Lithuania’s most prominent landscape painters. Varnas studied painting in St. Petersburg, Kraków and Geneva. In his memoirs, he wrote that he met Piłsudski in Zakopane and this was there, in Stefan Żeromski’s house, where he painted Piłsudski’s portrait in an Ainu costume. Piłsudski was 46 years old at that time. It is worth mentioning that in Żeromski’s novel titled Beauty of Life, written in Paris in the years 1911-1912, the character of Gustaw Bezmian was certainly created under the influence of stories heard from Piłsudski. The novel deals with two topics: the recovery of national consciousness by a person thrown into an alien environment in which he has already assimilated, and the search for his place in the homeland, to which he returns after many years of absence.

From January 1913, Bronisław Piłsudski attended lectures at the University of Neuchâtel as an auditing student. Since he was there for a short time, it can be concluded that his goal was not to get a degree; he was rather eager to learn museology with the Tatra Museum in mind. It is worth remembering that he visited numerous museums, including those in Sapporo, Tokyo, New York, Prague, Vienna, Berlin, Paris, London, and Brussels. In Poland, he used the knowledge and skills in museology gained in Russia and the West. In 1911, he presented a report titled “On the Tasks and Methods of Ethnography,” followed by three reports in the following year: “On Various Ways of Collecting Ethnographic Materials for the Zakopane Museum,” “Impressions from a Trip to Slovakia,” and “Memories from Japan.” In addition, he was the initiator and chief editor of the planned journal “Rocznik Podhalański”. Unfortunately, the first volume he prepared was published only after his death.

In 1916, the journal of the Swiss Ethnographic Society published the results of Piłsudski’s research on highlanders in a paper titled “Almen-Viehzucht im Tatra-Gebirge” (“Alpine Tundra Shepherding in the Tatra Mountains”). He had come to Switzerland a year earlier. He lived, among other places, in Zurich at the house of Gabriel Narutowicz, to whom he was related, but his place of residence was primarily the nearby Rapperswil, where there was a Polish museum with a well-equipped library. This is where he was sitting most often, reading and writing, and feeling the need for fulfillment.

Based on:

Antoni Kuczyński, “Bronisław Piłsudski (1866-1918), an Exile and Researcher of the Culture of the Peoples of the Far East”, “Niepodległość i Pamięć”, 22/2 (50), 7-93, 2015

Kazuhiko Sawada, A Story of Bronisław Piłsudski. A Pole Named King of the Ainu People, Sulejówek 2021