Timeline

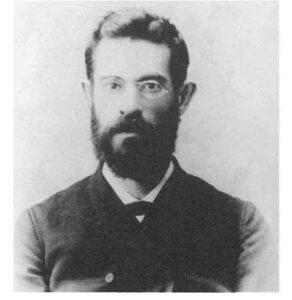

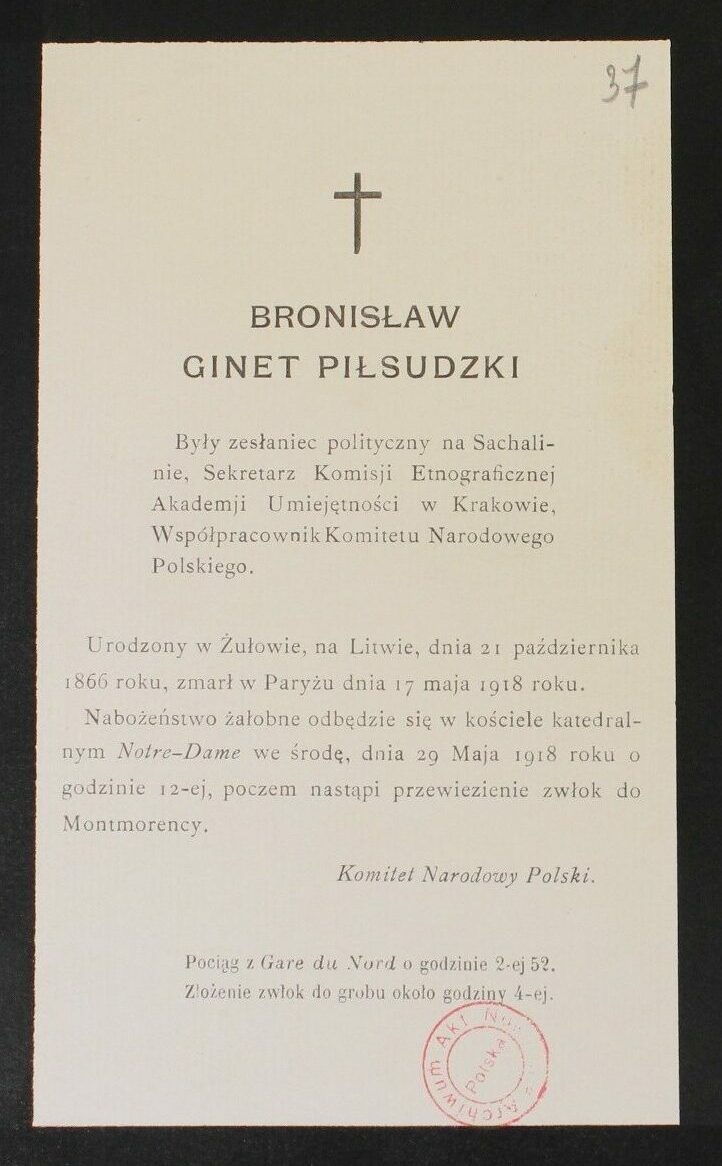

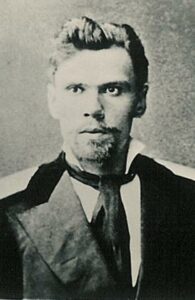

Bronisław Piłsudski – Timeline

1866

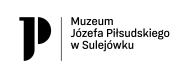

Bronisław Piotr Piłsudski was born on 2 November in Zułów (now Zalavas), in the Vilnius region, to a gentry’s family as the third child and the oldest son of Józef Wincenty Piotr Piłsudski (1833-1902), the Piłsudski variety of the Kościesza coat of arms (reversed), and Maria née Billewicz (1842-1884), the Mogiła coat of arms.

Bronisław Piłsudski’s Lineage

1875

4 lipca

Fire at the manor house in Zułów; the Piłsudski family moved soon to Vilnius.

1877

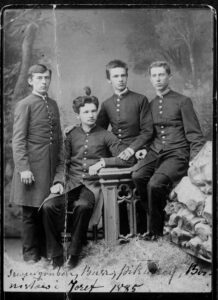

Bronisław Piłsudski began his education at the I Gymnasium in Vilnius, an elite school oriented in humanities, natural science, and mathematics, in the same class with his brother Józef who was one year younger.

1882

In the spring, the three Piłsudski brothers (including the youngest, Adam) and their friends set up the Spójnia Self-education Club, thus starting and getting involved in illegal activities.

During this period, Bronisław began to keep (until 1885) his Diary, which in the future would become a rich source of knowledge about the life of the Piłsudski family and the state of mind of young Bronisław.

1883

June

Bronisław Piłsudski was not promoted to the 7th grade. This was a very traumatic experience for him despite the fact that in the Russian education system at that time, the final examination in the 6th grade was intended to radically reduce the number of students (sometimes only a few of twenty would pass the exam). Józef passed this exam.

July

Bronisław changed the school, moving to the II Gymnasium in Vilnius.

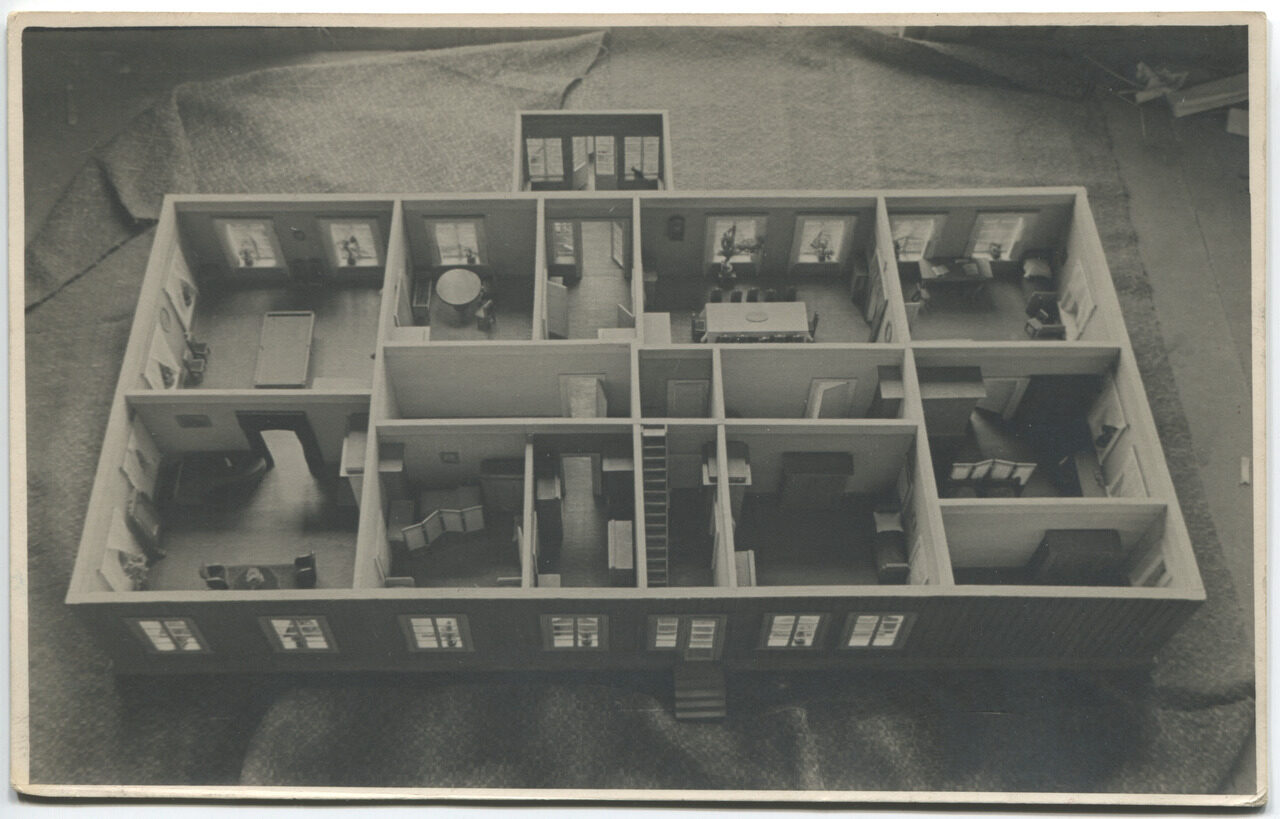

For the first time, he fell in love with Zofia Baniewicz who gave him piano lessons. Bronisław himself was very fond of playing the piano and in the future, in exile, he would ask his family to send him notes.

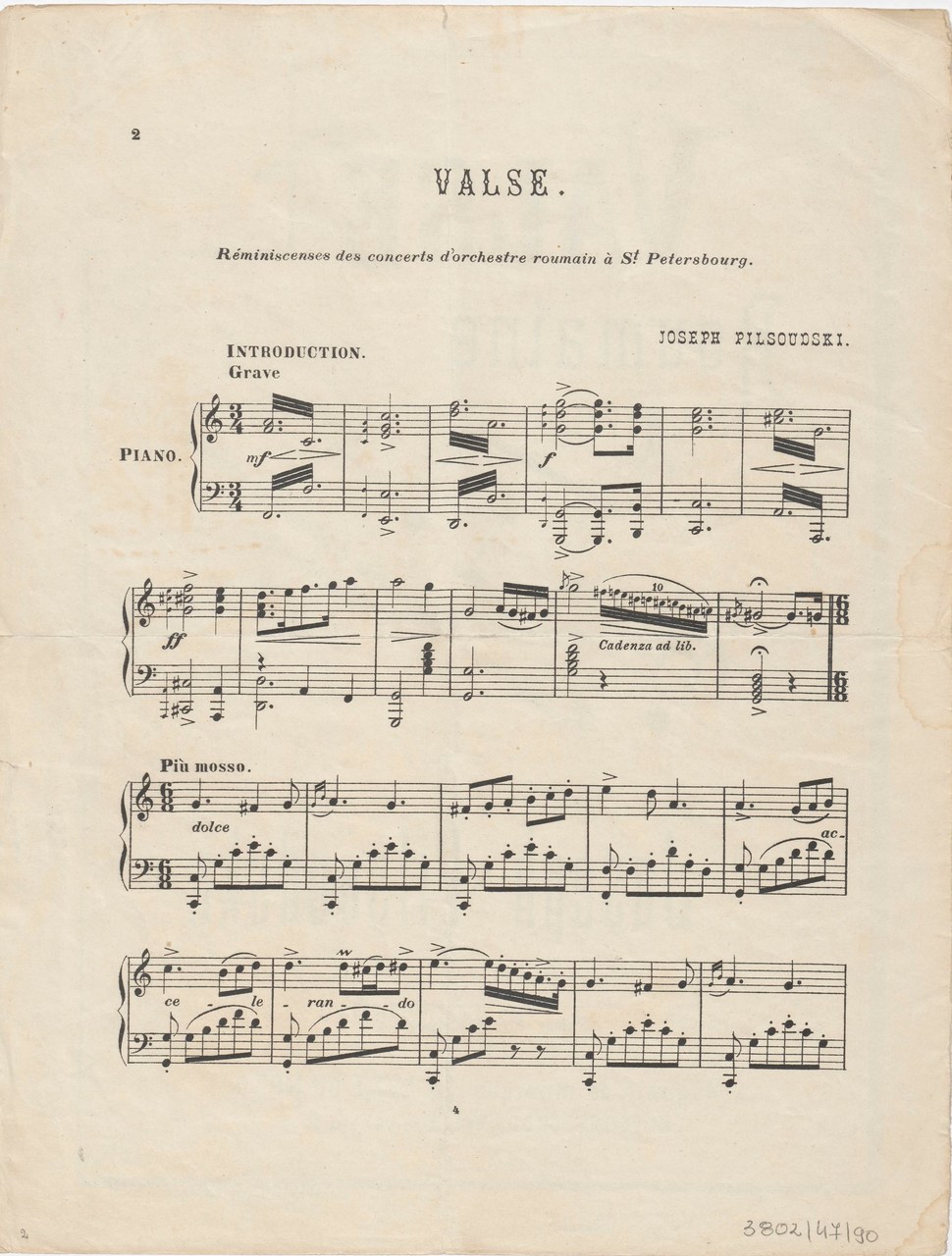

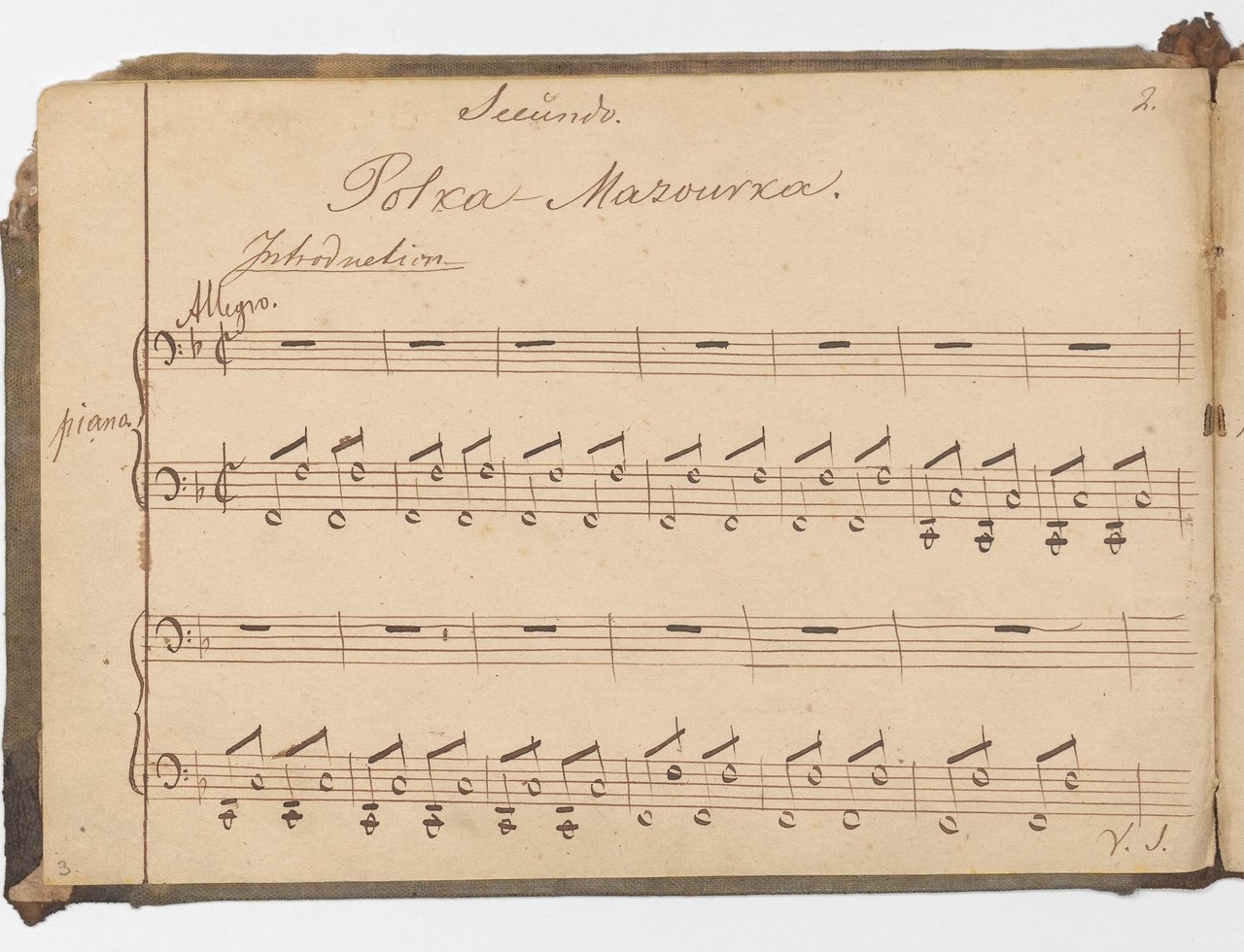

Notes of the composition by the Piłsudskis’ father, Józef Wincenty; from the collection of the National Museum in Warszawa

Valse roumaine, a composition by Józef Wincenty Piłsudski, performed by Alexander Opolski

1884

1 September

Death of Maria Piłsudska, Bronisław’s mother

1885

End of April

At her mother’s insistence, Zofia Baniewicz left for St. Petersburg.

August

Piłsudski successfully completed the 7th grade of the gymnasium in Vilnius.

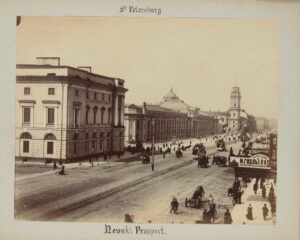

He left for St. Petersburg to continue his education and avoid a possible repetition of the negative “selection” on the exam after the 8th grade.

18 September

Bronisław began the 8th grade at the V Classical Gymnasium in St. Petersburg, referred to as Alarchin Gymnasium. He was very happy about moving to St. Petersburg because he found the atmosphere in Vilnius unbearable.

1886

June

Piłsudski graduated from the gymnasium.

August

On 10 August, he enrolled in the Faculty of Law at the Imperial University in St. Petersburg. He became acquainted with a lot of students, including those sympathetic to the revolutionary movement.

End of December

Bronisław Piłsudski spent Christmas in Vilnius; this was his last stay at home. During the Christmas holidays, preparations by the Revolutionary Faction of the Narodnaya Volya for the assassination of Tsar Alexander III were taking place, simultaneously in St. Petersburg and Vilnius.

1887

3 March

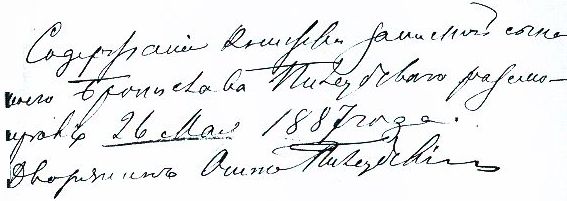

After the foiled assassination attempt on the Russian Tsar Alexander III, Bronisław Piłsudski was detained in his apartment, denounced by one of the conspirators, Mikhail N. Kancher, and imprisoned in the Petropavlovsk Fortress. His brother Józef, also detained in connection with the discovery of the conspiracy and interrogated, was administratively ordered to settle in the eastern Siberia, as a criminal penalty.

The detention is presented in more detail by the infographic, constituting a part of the permanent exhibition of the Józef Piłsudski Museum in Sulejówek, in Gallery Ziuk.

Zagadnienie aresztowania przybliża infografika umieszczona na wystawie stałej Muzeum Józefa Piłsudskiego w Sulejówku, w Galerii Ziuk.

15–19 April

During the trial in the Senate (all political cases concerning fundamental raison d’état, such as an attempt on the tsar’s life, were tried by Senate), the death sentence was imposed on fifteen defendants, including Bronisław Piłsudski.

23 April

Thanks to the amnesty announced by the tsar, Bronisław Piłsudski’s death sentence was commuted to fifteen years of penal labor and exile to Sakhalin.

8 May

The execution in the Shlisselburg Fortress of five convicts condemned to death, including Alexander Ilyich Ulyanov, the older brother of Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (later Lenin).

Farewell to the Known World

Preparing for this cruise to exile, Bronisław Piłsudski sent a letter to his father, reflecting the dilemmas of a young man sentenced to 15 years of hard labour. He is expressing his love and gratitude for all the blessings experienced at home, and is assuring his father that the memory of these ideals would allow him to survive this difficult time in exile.

18 May 1887 S.P.T. [Saint Petersburg] Preventive Detention

Dear Father!

I have been permitted to write to you once again to share my heartfelt thoughts and feelings. I’ve never had so many things on my soul to tell you about, but also I’ve never been so incapable of doing so as I am now. So please, understand me if my letter is a little clumsy or incomplete, but you need to know that as always I will write about everything that I feel deeply and truly in my heart.

A nice good life has passed for me, what I can only compare to a dream. Was I not in a deep and lovely sleep, forgetting almost all the reality around me, with my aspirations and feelings directed towards one goal, and flying in my mind under the clouds? Is it not a dream when a man is unaware of what he is doing, when he thinks or says one thing, and does another? I had to wake up, however in such terrible circumstances. I do not rail against my harsh sentence, even though it’s completely unnecessary in terms of improvement. It would be awful if only punishment or fear of suffering could bring me to my senses. On the other hand, however, the punishment as a compensation of the sense of justice, entitled me by law, was mitigated only by the monarchical grace. What’s more, when it comes to the matter of dissuading others from similar crimes, it probably is the issue that brings me the only consolation. I would be happy if my broken life could bring brave and fervent young men to their senses. I comfort myself that I will be suffering not only by my own fault, but also so that many others like me will not suffer, so that looking at me, they could choose to change their intentions and become useful members of the society. Unfortunately, I feel sorry for the beautiful years of my life, and I regret my lost dreams, but it’s not difficult for me to part with them. Not just one personal advantage in life was I looking for, nor a few pleasures I have expected. If anyone was destined to be a bitter example to others, it was even better it was me rather that my brother or any of my good friends. With their skills and personalities, they will be able to be used for more benefit for the society than I was. Why dwell on my lost dreams when in fact I’m happier than many, or most other? Almost 20 years of my life had passed without any worries and troubles. I’ve had the opportunity to enjoy all the “higher” pleasures, satisfy my even temporary desires, while so many people today lead their lives working hard, striving for a piece of bread, often unable to meet their basic needs. However, I am not able to calm down. Can one be calm when his conscience needs to be justified and finds no satisfactory answer? When I can give only one unfavorable answer to this persistent questions – how have I paid you back, my Father, for your concern for my education, for which so much money has been wasted? What is my compensation for those who have worked on me? What have I given in return for all the love surrounding me, how have I proved my love for all my dear people?

How terrible is the situation of a man who knows that instead of gratitude, he is bringing sadness, who knows that more than half of his life, if not all of it, has been going by without any good. It’s hard to realise that you have been given sacred responsibility but cannot fulfill it. The thought of such unfulfilled responsibilities brought me to my senses, and this reflection will also keep my spirits up during the time of serving my sentence. On the day when it was announced to me that by the emperor’s grace my life was spared, I promised myself I would honor it with all my might, until at last I would reenter into society, and even partially repay the debt of gratitude I owe to you, my Father, and to many others, and I would wash away my serious crime with a better life.

I know that my situation is very difficult, and that I will have to fight against myself at every turn. I will have to prepare my weak body for the toughest conditions, to build up my weak character, to get rid of uncertainty and constant doubts, and to have more faith in myself, so that my weak would be strengthened. This is essential for me if I wish to truly come back to you, and not just prolong my miserable existence. As for your two remarks about Christian love and God, rest assured, my Father. The rules of morality found in Christian doctrine have always been an ideal for me, and my soul is soaked in by them. And except for departing from them for a while, I promise never to abandon them again. As for God and a variety of teachings of materialists, I must admit I’m not competent in terms of the scientific point of view.

I must say that even in the fortress I have become acquainted with some aspects of the so-called philosophy of nature. In my opinion, the existence of an inconceivable and astonishing us by His power, the omnipotent Being, the God, has been best proved by the materialists themselves. Yes, they can explain conditions under which different kinds of phenomena arise, but not their essence or cause. They can reduce all things to matter, but cannot answer who created the matter, who gave it characteristics expressed in the form of correct, unchanging principles. Who cares about their strict observance? What I can see are not single miracles, as uneducated people often call new to them phenomena that as a result attract their attention. In my opinion, everything without exception is a miracle that prove the manifestation of God’s will, starting with the simplest process happening before our eyes, and ending with the perfection found in nature, this harmony and astonishing order in the movement of infinitely many universes, in infinity immeasurable space.

Forgive me, all of you, and especially you, my Father, if I have been unjust to you in any way. I will never forget your love, and God willing, I will repay you not less one day. Good bye, my brothers and sisters! How I wish I could give you a portion of my love, so that you could love even more your dear Father, each other and everyone around. How much I wish I could share all my experience with you, so that you could be better and happier than me. I was older, but didn’t always know how to use this fact properly. Now I give you everything. As I get back in 15 years, I will definitely need your experience and advice. Now, try to replace me when my Father is embittered over me. Try to comfort Him and lessen His suffering with your love and good behavior. Never forget your duties, and do not consider only those that suit you – as is often the case with young people. Learn and develop systematically, don’t be afraid to solve problems for which you don’t have an explanation yet. But above all, remember your morality and your character, since the main deficiency in life is not the lack of mind development, but the lack of character. Be modest (but do not confuse this with degrading mediocrity), listen to advice of the elders, with whom I now agree on many things, even though I denied them during my “blindness” (being overwhelmed by my passion). Love the truth and never be afraid to admit your mistakes. It’s better to improve yourself late than never. And now, if I have earned your love and trust, give me, please, your word to always look after yourselves, even in the smallest of things. And whatever mistakes you notice in yourself or hear of them from others, do not stop until you get rid of them. And now, good bye. I am convinced that all of you without exception, filled with true Christian love for everybody, will successfully enter into the life that would be closed to me for a long time.

Good bye, all my dear relatives, comrades, acquaintances. My beloved Father, do not give in to feelings of sadness, since it is necessary to accept what we cannot change, or return by our human power. Awareness of your torment will bother me even more. All of you, know that I have loved you, love you, and will never cease to love you, and be sure, I do not yet lose hope to prove it to you by my deeds. Forgive me once again and see you in the twentieth century.

Your Bronisław

This letter closed the bygone time and marked a new path into the unknown.

The father tried unsuccessfully to obtain a pardon for his son. He saw him twice during his trial.

At the end of May, Bronisław Piłsudski and his comrades were transferred to the Butyrka prison in Moscow for a few days. After three months spent in a solitary cell, he was finally able to stay with his colleagues from the trial, whom he didn’t know well, as he had been involved in the assassination by chance. Nevertheless, he experienced it as relief from isolation.

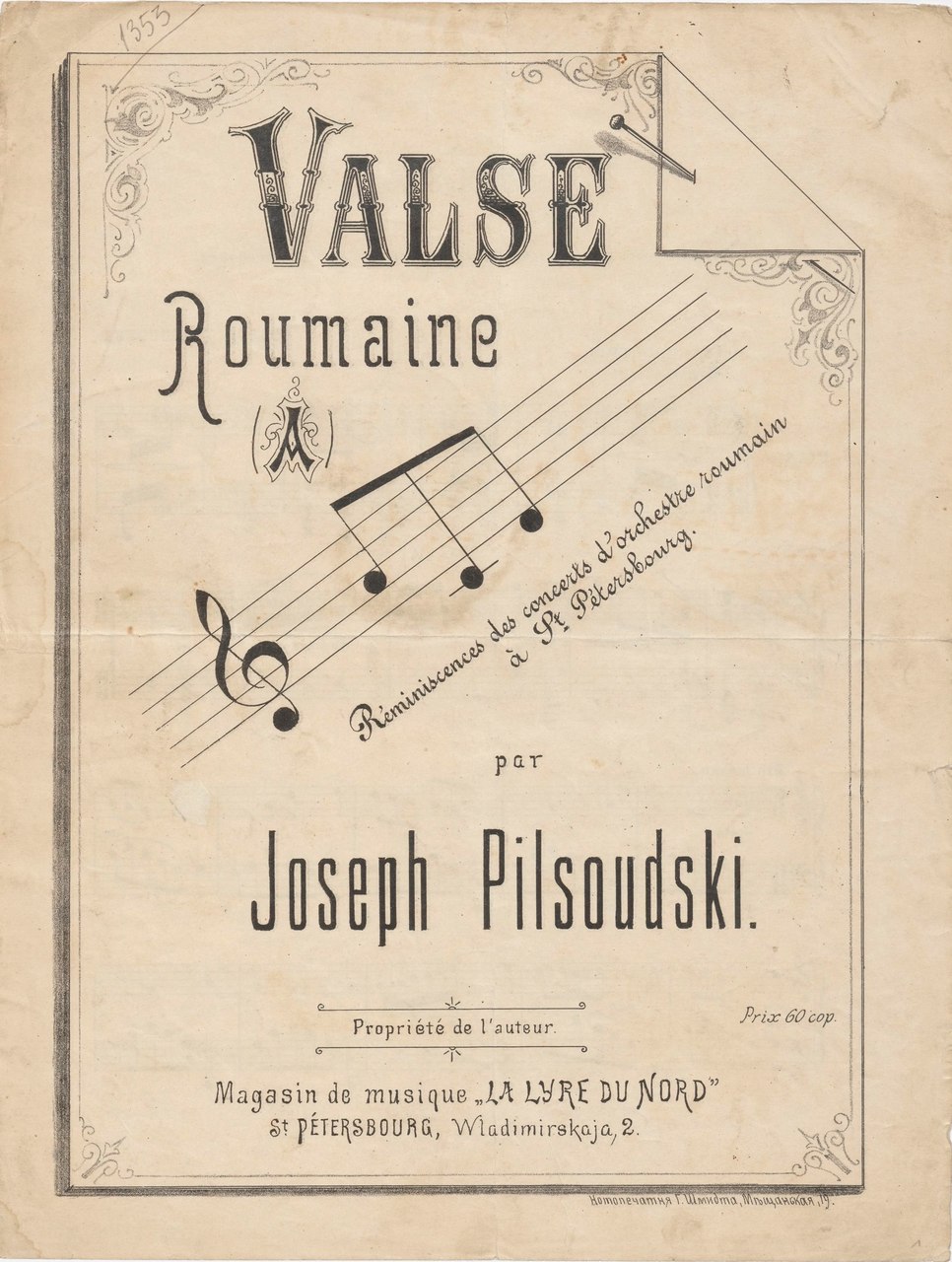

Butyrka prison in Moscow

Butyrka prison in Moscow

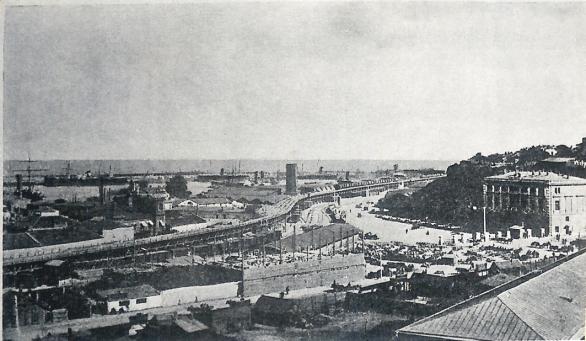

On 6 June, they boarded a train to Odessa, a rapidly growing port that mainly operated ships and war transportation including deportees transportation system. A railway station, a prison and a jail were built near the port, and the entire district of Kulikov was living by the services and clerical work of the prison. It was there that the exiles sent to a distant island were given the nickname “Sakhalints”.

Port of Odessa at the end of the 19th century; collection of V. Latyshev

Port of Odessa at the end of the 19th century; collection of V. Latyshev

On 9 June 1887, Bronisław Piłsudski’s ship to Sakhalin left the roadstead in Odessa. In addition to hundreds of criminal prisoners, there were four “political” prisoners on board convicted with Bronisław: Mikhail Kancher, Petr Gorkun, Stepan Volokhov and Ivan Juvachev.

As he wrote in the letter to his father, Bronisław Piłsudski began his route to an unknown world, which he was to leave only in the next century.

27 May

Bronisław Piłsudski’s deportation began; he set off by train from St. Petersburg via the Butyrka Prison in Moscow to Odessa, where he arrived on 6 June.

9 June - 3 August

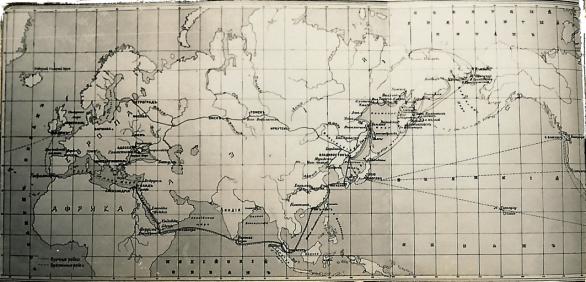

From Odessa, he took the “Nizhny Novgorod” ship of the Russian Volunteer Fleet (Dobrovolnyi Flot) carrying 525 prisoners via the Suez Canal, Colombo, Singapore, and Nagasaki to Sakhalin;

The Route to Exile – a Cruise

Scheme of cruises of the Volunteer Fleet to Sakhalin; photo from the collection of V. Latyshev

Scheme of cruises of the Volunteer Fleet to Sakhalin; photo from the collection of V. Latyshev

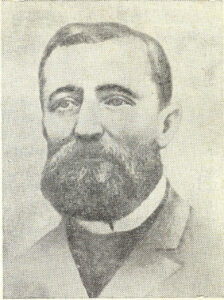

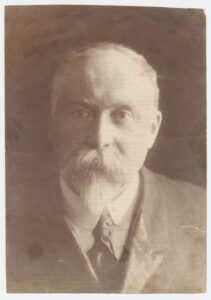

Edmund Płoski (1859-1942) made a similar cruise as Bronisław Piłsudski two years earlier. From his notes, we can learn about the detailed route of the deportees transportation to Sakhalin on the “Nizhniy Novgorod” ship owned by the so-called Volunteer Fleet operating cruises under the government service.

It’s worth mentioning that after the arrests of the Great Proletariat members in 1883 and numerous trials, which resulted in heavy punishments including the death penalty, Płoski found himself in a group of several hundred activists sentenced to exile. Initially, he was imprisoned in the 10th Pavilion of the Warsaw Citadel for a year. According to biographers, he broke down under the pressure of investigation and gave incriminating testimony, but soon recanted it. He was sentenced to 16 years of hard labour and deprived of any rights. A place of his exile was the island of Sakhalin, and he stayed there with his wife for 12 years. Płoski spent the next few years in Blagoveshchensk. After the revolution of 1917, he managed to leave for Japan, and then made his way to Europe, settling in Limanowa in Galicia, where he worked as a clerk. Edmund Płoski and his wife met with Bronisław Piłsudski in Aleksandrovsk in Sakhalin, in Nagasaki in Japan, and later in Limanowa. After Poland regained its independence, Płoski became the President of the District Court in Włocławek. In the Second Polish Republic, he became a senator, and in 1930, he retired.

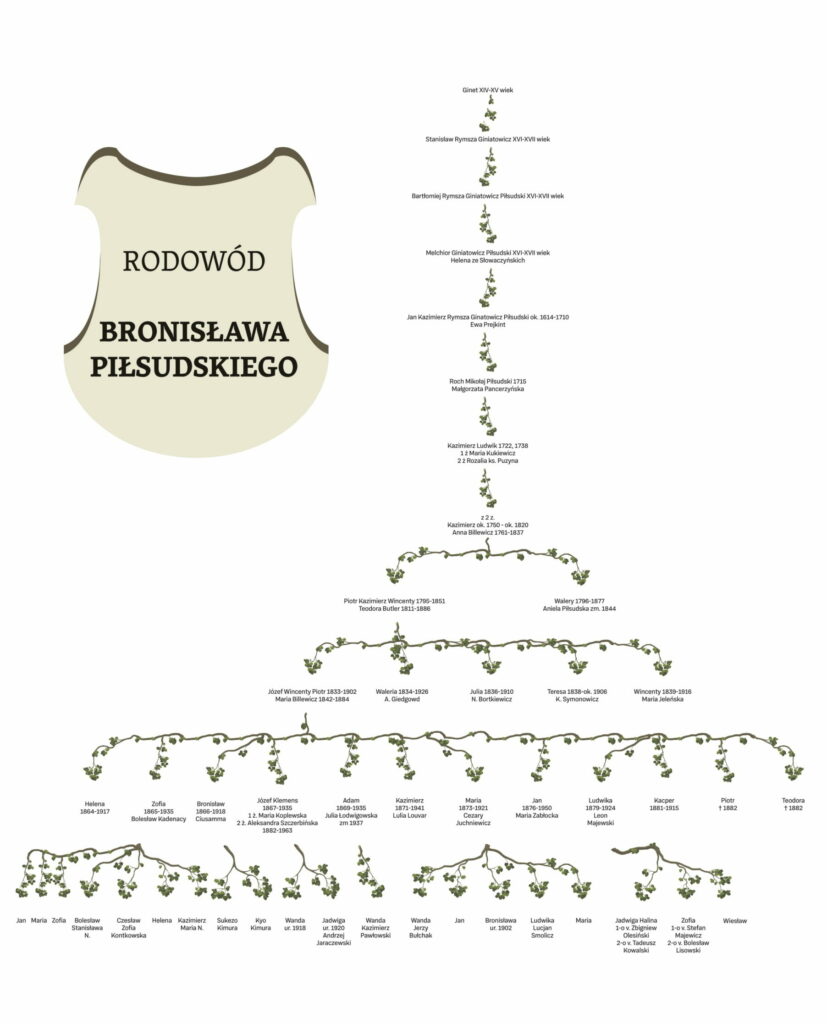

The mentioned ship operated regular cruises from Odessa to Sakhalin, sailing around the southern Asian peninsulas of Arabia, India and Indochina, and transporting exiles destined for Sakhalin. On the way back to Odessa, the tea from Shanghai and some goods from India were imported. The prisoners’ quarters were located below a deck in the front part of the ship.

Model of “Nizhniy Novgorod” ship from the Museum in Yuzhno Sakhalinsk; photo by Prokofiev

Model of “Nizhniy Novgorod” ship from the Museum in Yuzhno Sakhalinsk; photo by Prokofiev

This is how Płoski described this journey:

“Cargo storages located under the deck were fenced off by iron bars. Thus, long corridors were created on each side of the ship, some 50 or more meters long and about 5 meters wide. The middle part of the ship, more or less of the same width, was intended for guards. It included openings leading to the lower floors of the ship and stairs connecting the shell of the ship with the deck. Along the sides of the ship, the bridges went from two floors. The detainees were supposed to move there, usually in a lying position, because only a narrow strip of the floor, about two and a half meters wide, could be used for traffic, which for two hundred or so casemate passengers made all motion extremely difficult. At one ending of this casemate in the front of the ship, there was a small toilet on the 2-3 steps platform, intended also for washing. Since nothing wooden was inside, it was allowed to smoke tobacco there while in the sleeping casemate smoking was strictly forbidden. In the wall of the ship, just under the ceiling (deck), there were ten little round windows, the size of a large plate, in which a head could hardly fit. Whenever the sea was calm and the windows (portholes) could be kept open, they let in some light and fresh air. At the condition of high waves, the windows were closed and tightly screwed so that it was impossible to open them manually. In that case, the only ventilation was provided by the pipes laid on the deck and the opening in the central casemate leading to the deck. In the hot zone, such ventilation was insufficient, so the people inside the casemate suffocated from lack of air. From time to time, one or the other fainted, and was carried on deck. They were doused with water, revived, and brought back into the casemate. Sometimes, several dozen of such fainting people were carried out. In order to refresh the air in the casemate, all were taken out on deck to take a shower. Anyway, this was arranged on such a narrow surface that people had to stand body to body, closely to each other. Fresh ocean water was sure very refreshing, but such close contact of the bodies resulted in infection with skin diseases, especially with the tropical ulcers prevailing in this cramped conditions and dirt. It was not a malignant disease, rather easily treatable, but it caused a lot of suffering, as the inguinal glands swelled, and all movements caused severe pain. After getting out into a cooler area, the ulcers healed quite quickly.”

Another quite severe deprivation in the tropics was the lack of drinking water. The river or distilled water used previously for cooling the ship’s machinery was kept in a big and tightly covered barrel. Prisoners could drink it through a tube. This tool however caused diseases and evoked disgust, so only a few used it.The governor of Odessa held the highest authority on the ship and could sentence anyone to death without legal process. When a fire broke out on board caused by the prisoners, he ordered to hang them for their misdemeanor as an example, but the execution was not carried out. The guilty received just a few dozen lashes each, which they were very happy about.

In particular climatic zones, the deportees faced heat, harsh cold, lack of air and seasickness. It was not always possible to enjoy the view through the small windows. Płoski was not impressed by the sight of Constantinople. He wrote that the trip through the Suez Canal took them two days, after which the ship sailed for the Red Sea. A great surprise for the prisoners was their being taken out on deck in small groups and unchained from shackles:

“How lightly and freely the feet walked without this burden, and in particular, how pleasant it was to get rid of the incessant clanking caused by the walking of dozens of people. At first, this clanking was a real torment for the ears and the brain. Over time they got numb, and no longer responded to it with suffering. But the suffering was there in some subconscious, and at one time or another it became more severe. This so-called getting used to something does not imply lack of suffering at all; you just stop pay attention to it. Throwing off the shackles was the first step towards freedom.”

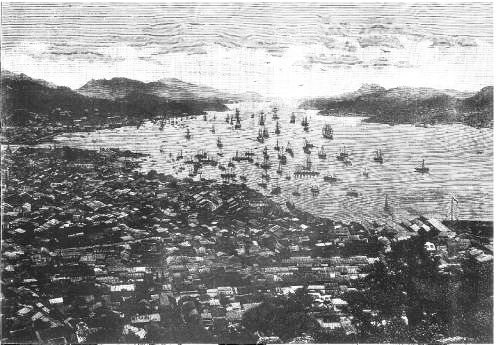

The great heat during the crossing of the Red Sea was an absolute torture. Many of the deportees fainted even several times a day. Płoski writes that this five-day period was a time of great agony. It was only when they went out into the Indian Ocean that it became a boon. Even though the wind was blowing and the prisoners were seasick, they endured it better than the exhausting heat causing many passengers to take their clothes off and walk around naked. The heat also affected the lack of appetite, although the food improved appreciably. They were given the soup with meat, the same as the sailors got, and as much as they wanted. At the ports in Colombo and Singapore, southern fruits were purchased for the prisoners, and they were getting even red wine and greater tea portions than before. This was intended to prevent spreading of scurvy among the detainees. A great sensation was the distribution of pineapple-scented soap, which was consumed by some. The port in Nagasaki at the end of the 19th century; photo from the collection of V. Latyshev

The port in Nagasaki at the end of the 19th century; photo from the collection of V. Latyshev

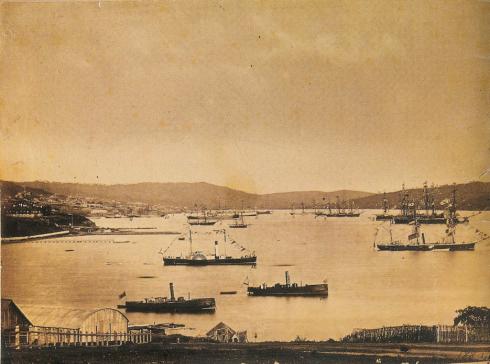

In July, the travelers crossed the equator. It was only near Nagasaki that it got cooler and the health condition of many improved. Fortunately, the ship on which Płoski sailed, was not plagued by troublesome epidemics, as was the case on other ships, e.g. on the “Kostroma” with women sailing to Sakhalin, including Płoski’s wife and families of deportees. About 60 deaths a day happened there. After a few days’ stay in Nagasaki, the ship set for Vladivostok. Now everyone had to put their clothes on to prevent cold, especially at nights. Some even received sheepskin coats, even though it was mid-August. The week-long stop in Vladivostok was a kind of quarantine.

The port in Vladivostok at the end of the 19th century. In the depths of the bay, on the right side, there is the “Nizhniy Novgorod” ship; photo from the collection of V. Latyshev

The port in Vladivostok at the end of the 19th century. In the depths of the bay, on the right side, there is the “Nizhniy Novgorod” ship; photo from the collection of V. Latyshev

A medical commission came on board to inspect the prisoners and examine their lungs and hearts. No one was detained. Everyone was anxiously looking for Sakhalin. Many asked, how far was Sakhalin from America. Was there any idea of escaping to this distant and better land? Nobody seemed to know. Płoski’s explanation about these unrealistic dreams and the possibility of escaping were received with great disbelief. At the end of August, “Nizhniy Novgorod” reached the coast of Sakhalin. Everyone wanted to see this hostile land, where they were supposed to spend the rest of their lives. However, a fog covered the entire island:

“The ship was anchored far from the shore, rocking on the waves. From time to time, the inhabitants were notified of its arrival with the noise of sirens. Then the ship waited for boats to unload men and goods. We were looking forward to it too. The thing about prison life is that you always look forward to a change, even though you know it could be for the worse. But the present reality, even if quite calm by the standards of prison situation, is soon annoying in its lack of activity and regular forced contemplation, so there is always a desire for a change. And it seems that the times cannot be worse than is now. So the delay in the arrival of the boats for unloading caused an impatient desire to speed up the process.”

The marina in Aleksandrovsk with a pier. The ship itself did not dock there because of the shallows, but only barges sent for passengers, and the loads picked up from the ship that was docked further from the shore.

The marina in Aleksandrovsk with a pier. The ship itself did not dock there because of the shallows, but only barges sent for passengers, and the loads picked up from the ship that was docked further from the shore.

Three large boats with a capacity for 50 people each arrived. In total, there were 800 passengers on the ship, so the boats had to arrive several times. A huge wave on the sea and rain caused terror among the passengers. The shore, although visible now, was still distant for them and the little boats were leaning to the sides, causing a panic fear:

“That one-hour sail to the harbour caused more fear among the detainees than the whole cruise from Odessa to the shores of Sakhalin. But everything comes to an end. Despite heavily soaked, we stepped safely on the pier of the marina.”

Barge with deportees docked at the harbor in Aleksandrovsk; photo from the collection of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences, donated by Bronisław Piłsudski

Barge with deportees docked at the harbor in Aleksandrovsk; photo from the collection of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences, donated by Bronisław Piłsudski

On the basis of

Anna Maria Stogowska, A Ship for Exile. Edmund Płoski on Sakhalin; https://zeslaniec.pl/51/Stogowska.pdf

on 3 August, the ship arrived at the Alexandrovsk on the west coast of northern Sakhalin.

Bronisław Piłsudski after his arrival into exile, as seen by Edmund Płoski

An excerpt from Edmund Płoski’s memoirs:

I remember the first day when I met him, and his great joy when he heard the first Polish words on Sakhalin. I took him to my apartment. There, like a child, he cried and told with the honesty the story of his exile in all details. He had fell victim to a tragic judicial error, so common in the Russian justice system.

In St. Petersburg, he had numerous Russian friends from his gymnasium days and maintained contacts with them without knowing or being interested in what they were doing. He dreamed of science and his future career in this field. Among his close colleagues, he considered Kancher as one of his dearest friends. What brought Bronisław close to this young man were both the positions of their families and their similar level of culture. Therefore, the two were close friends in St. Petersburg. As a friend, at Kancher’s request, he allowed him to use his room. This was because it had a separate entrance and was isolated from the neighborhood. Kancher justified his request by the need of organizing meetings with friends, lectures, or something similar. Of course, Bronisław was aware that friends’ meetings, lectures, or reading books together were not legal, but he never supposed – and such a thought never entered his head – that terrorist plots or bombs were being prepared there. Yet this was exactly what Kancher’s friends were doing with his personal participation. When the conspiracy was discovered, the participants with bombs in their hands were arrested. Kancher, suffering from depression in prison so common among inexperienced young men, not only betrayed Piłsudski, but what was worse, apparently wanting to save himself, testified what he was suggested, that Piłsudski consciously made his apartment available for this revolutionary work in St. Petersburg and Vilnius. Piłsudski’s denial of these accusations confirmed policemen in the belief that Piłsudski was among the organizers of the coup, and was almost its mastermind. In court, Kancher retracted his testimony, but it did not help anymore. Therefore, while these young men, caught with bombs under their arms on the Nevsky Prospect where the tsar was supposed to be passing by, were each sentenced to 10 years of penal labor, Piłsudski was sentenced to 15 years. On the way to Siberia, they were together in one compartment of the ship. Kancher apologized to Piłsudski for his crime against him and begged for forgiveness, which he received from the tender-hearted Bronisław. He promised Kancher both to forgive him and forget his guilt, and not to complain to his comrades.

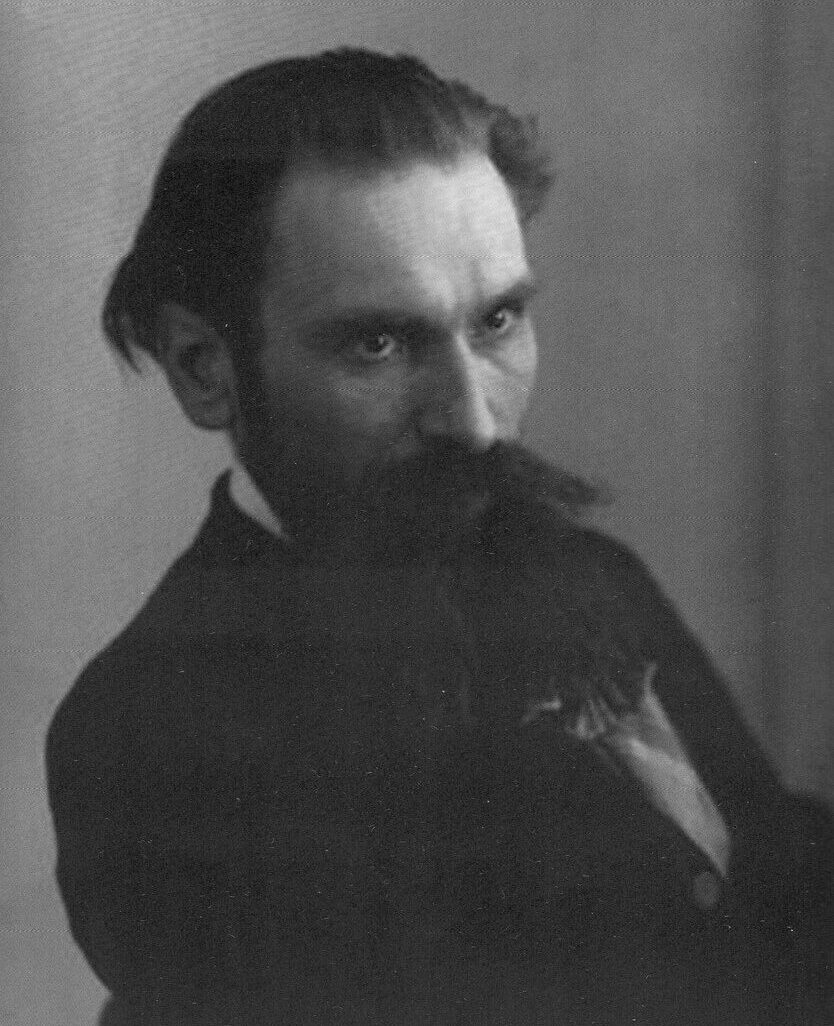

He told me about it, but obliged me with a word of honor to keep it a secret. The secrecy, however, did not hold, despite our intention. In our apartment, which was very poor and primitive with bare timber walls, and the floor full of cracks, yet decorated somewhat with the efforts of women, Bronisław cheered up. It seemed to him that freedom was returning; that he was back in the countryside, in the outhouse at his father’s estate, and with his family. In the prison, he seemed much older than his age would indicate, perhaps as a result of the fatigue that was reflected on his face. Here, on the contrary, I saw a young boy, light blond, with fine gentle blue eyes, animated and cheerful. The expression of dull despair I saw on his face in the barracks disappeared almost completely. In a conversation about the future ahead of him, he described images of serenity and hope.

9–12 August

On foot, together with other convicts, Bronisław Piłsudski made his way to the prison in the village of Rykovskoye (now Kirovskoye) in the Timovsk District.

The Fate of the Other Convicts

Stepan Volokhov

Stepan Volokhov

Petr Gorkun

Petr Gorkun

Ivan Juvachev

Ivan Juvachev

The three-day period of rest after the trip passed quickly. It was spent mainly on getting to know the surroundings of a new place and conversations with Płoski. Because of his connections, when the time came for physical labour, the political exiles who arrived with Bronisław worked no more than until dinner. The rest of the day they could relax or remain outside the prison until 9 p.m., when their attendance was checked. Recalling the beginning of his stay on the island, Płoski mentioned the welcome announcement made by the prison warden who informed that the local authorities were not interested in the prisoners’ past or the crimes they had committed. Their fate on the island would be determined by their behavior there and now. He stated also that those who were willing to work hard could even get some relief and finish serving their sentence much sooner. No one would guard them or put in chains. They could walk freely within the settlements, and could even run away if they wanted; no one would interfere. There were no guards at the barracks and dugouts, or walls around the buildings, however the exiles would not escape far, for the whole island was a prison, surrounded by the sea, and in the forests they could die of starvation. For misconduct and disobedience, they were threatened with whips.

After a short stay in Aleksandrovsk, Piłsudski and his companions were sent to inland. Some of the deportees were directed to the Tymov district and settled in the large village of Rikovsk, and Bronisław was one of them. The governor of the district, Cossack Butakov, was considered a good host. His major task was developing the entrusted land with the help of exiles. The valley of the Tym River flowing east into the ocean was suitable for agriculture and cattle farming. However, the climate there was harsher than in Aleksandrovsk. Winters were even more freezing, and summers warmer with fewer rainfalls, which accelerated the ripening of cereals. The exiles Aleksandrin, Volokhov and Gorkun were entrusted with the land and animals, and even founded an agricultural cooperative, but their “ideological” disputes soon destroyed this whole concept. Płoski writes that Juvachev and Piłsudski received a meteorological station as their field of labour with an adjacent apartment, and until the end of their stay in Rykovsk, their ordeal was relatively light.

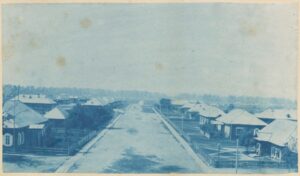

Street in the village of Rykovsk in the Tymov region. On the right, there is a prison hospital, on the left from a distance – a prison; photo from Bronisław Piłsudski’s album in the collection of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences

Street in the village of Rykovsk in the Tymov region. On the right, there is a prison hospital, on the left from a distance – a prison; photo from Bronisław Piłsudski’s album in the collection of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences

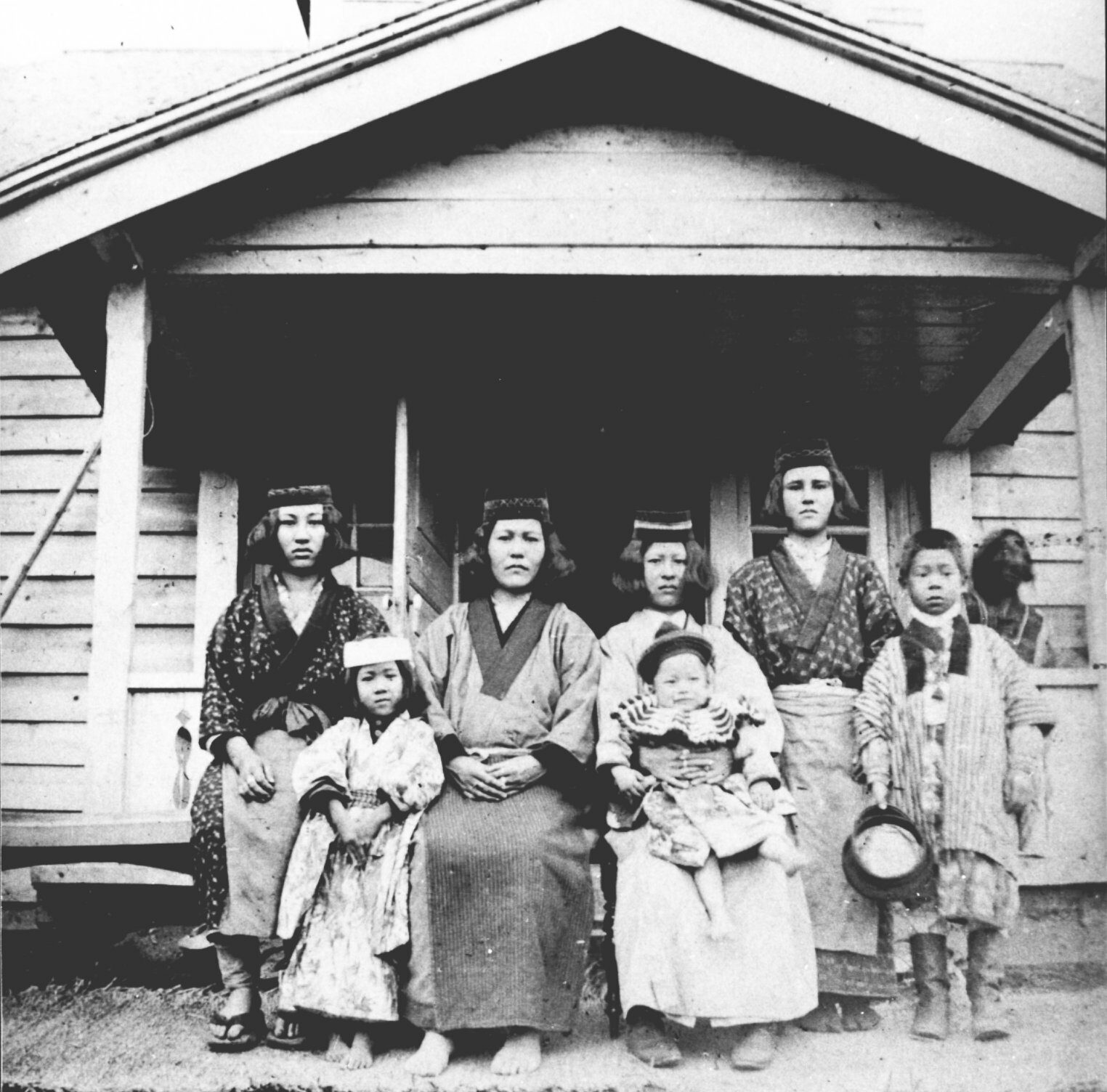

Daughters of settlers with students of Piłsudski in the garden of the meteorological station; photo from Bronisław Piłsudski’s album in the collection of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences

Daughters of settlers with students of Piłsudski in the garden of the meteorological station; photo from Bronisław Piłsudski’s album in the collection of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences

Kancher was imprisoned in Little Tymov, where he became an assistant to the prison warden as his skills of organizing the prisoners’ work were highly valued. When the locals learned about his role in the assassination and his slander of Piłsudski from the “Swobodna Rossja” magazine, this transgression was not forgiven him. A peer court was appointed, which sentenced the guilty to voluntary death. Płoski wrote, that “after a few days, Kancher carried out a sentence on himself with a double weapon – with a dose of poison and a revolver bullet”.

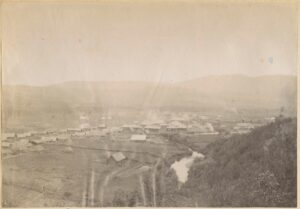

Village of Little Tymov; photograph from Bronisław Piłsudski’s album in the collection of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences

Village of Little Tymov; photograph from Bronisław Piłsudski’s album in the collection of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences

On the basis of

Anna Maria Stogowska, A Ship for Exile. Edmund Płoski on Sakhalin; https://zeslaniec.pl/51/Stogowska.pdf

August - December

Piłsudski performed the work assigned to prisoners sentenced to labor (logging, helping in the construction of the Orthodox Church), and was also involved in teaching the children of officials and forced settlers who were ethnic Russians.

Photo of the village of Rykovskoye and the iconostasis of the Rykovskoye Orthodox Church taken by Bronisław Piłsudski; from the collection of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences

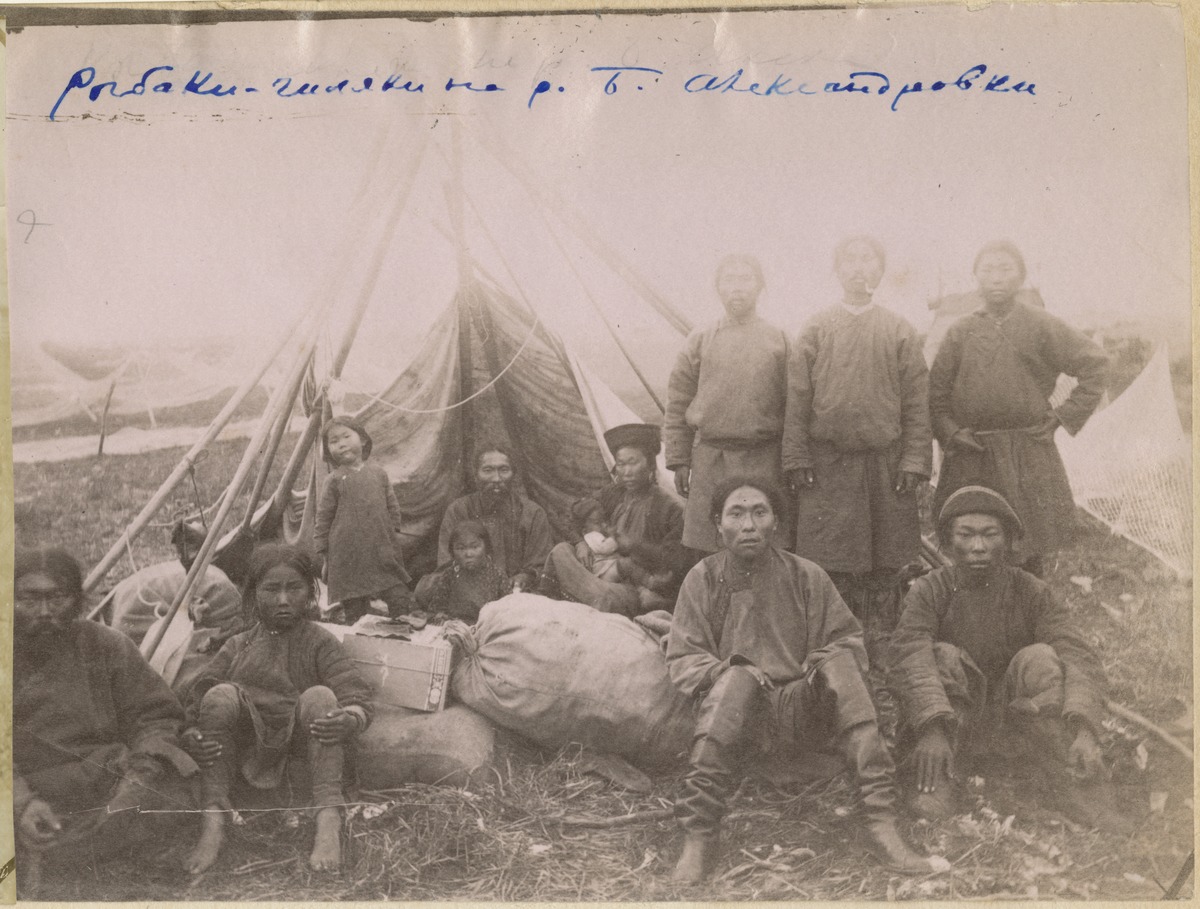

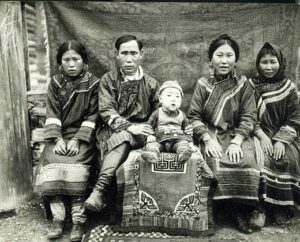

This was the first time Piłsudski came into contact with the culture of the then called Gilyak people (the proper present name Nivkh), the indigenous people of Sakhalin. As he wrote, “the only morally uncorrupted community on the entire island. […] I got close to these people who were dying out, treated them, vaccinated them for smallpox, taught them to read and write, and was an interpreter and advocate in relation to the authorities.”

The journey of the Gilyak family from the Alexandrovsk District to the Timovsk District and Fishermen, Gilyaks, on the river Bolshaya Aleksandrovka; from Bronisław Piłsudski’s album of photographs of Sakhalin; from the collection of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences

1888

5 October

Józef Piłsudski, Bronisław’s younger brother, submitted a written request to the minister of interior for transferring to Sakhalin. The request was denied.

1889

January

Bronisław started working in the office of the Timovskoye District police station as a clerk.

1891

January

He met a Russian ethnographer, Lev Yakovlevich Sternberg (1861-1927), exiled to Sakhalin in 1889, who was visiting the village of Rykovskoye. Sternberg inspired Piłsudski to undertake a systematic study of the Nivkh culture.

1 May

Piłsudski began to write a Sakhalin diary (kept until 20 March 1892) of his work in the garden established together with four other political exiles convicted in the same trial. Together they set up an agricultural cooperative which, however, had a short life.

1893

July

Probably this year, Bronisław Piłsudski began his systematic work on the vocabulary, tradition, and culture of the Nivkh people.

A song of the Nivkh people

Song of the Nivkh people written in the Russian transcription of their original language by Bronisław Piłsudski and dedicated to him; translated into Russian by Bronisław Piłsudski; Based on the “Izvestiya Instituta nasledija Bronislava Pilsudskogo, No.1, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, 1998, p. 111

From Russian ranslated into Polish by Jadwiga Rodowicz-Czechowska and from Polish into English by Piotr Jaskólski

Before my departure from Sakhalin, some Gilyaks came to Rykovsky to bid me farewell (31 January 1899) and some of the women expressed their wish that I write down the songs they dedicated to me. This song was dictated by Pimka’s wife, a quite greedy old woman who judged me in terms of my material possessions. She called it Chvinend tuhus and Chekanu tuhus.

Chvinend tuhus (words caused by grief for you)

You are going to leave for the continent.

You will abandon me and go away.

I love you. Young children and adult women

They are grieving for you.

And you are happy to leave.

I feel sorry, but what can I do?

You will forget me,

You will think and abandon.

I feel sorry, but what can I do?

You were like a father;

When we wanted to eat,

You did everything so that we could

Have food to eat.

You were always like a father.

But if you leave, you will abandon me,

And who is to say that I will be able to eat,

And who will pay for my food?

I keep thinking about myself,

That I feel sorry for you,

While you not even think of me.

Transcription:

Chi kektykhvinynd

Ninykhviinynd

Chi eeimund/ machkyn shank/

Ulyakhyndinyine/

Chvinefuroyanilio

Chi akhpkhohol’ khisvpin

Ynykhvijnyna/ kerifur

Ianilechvinyfur

Ianilepytykkhetakyrykhariuivo

Ian itiawkhnany/ nundnunditkh

Inuty/ ershparanta/ chi nynynykh

Vijkhyihynkra/ natitygyn

Ininda/ natchkhakish

Ininda/ koholimikhish

Chvinefure/ hantokhehrilio

Bronisław worked at the weather station in Rykovskoye, along with another political prisoner, Ivan Petrovich Yuvachev.

1894

December

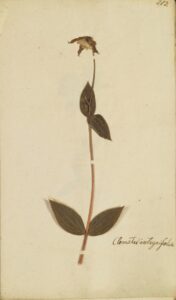

At the behest of the authorities, Bronisław Piłsudski undertook botanical research for the museum in Khabarovsk. During his trips to the mountains, he collected plants and established a herbarium.

1896

14 May

By the tsar’s decree (issued on the occasion of the coronation of Tsar Nicholas II), Bronisław Piłsudski’s sentence was shortened by 1/3 (Piłsudski’s father unsuccessfully submitted petitions for shortening the sentence also in April 1892 and November 1894).

July - August

Bronisław Piłsudski went to the south of Sakhalin, to the Korsakovo District, to install a weather station, where he met the Ainu people for the first time.

1897

27 February

The end of Bronisław Piłsudski’s sentence; he registered as a peasant from the village of Rykovskoye in the Timovsk District.

June

The research group Amurskiy Krai (Region) Research Society (OIAK), a branch of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society, made an unsuccessful effort to hire Piłsudski at the museum in Vladivostok.

1898

20 April

Piłsudski completed his first work in the field of ethnology, entitled “Nużdy i potriebnosti sachalinskich Giliakow” (Location and Needs of the Gilyak People in Sakhalin) which he published in Khabarovsk in the “Bulletin of the Amur Branch of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society” (1898, vol. 4, no. 4).

May - August

Work at the weather station in the village of Rykovskoye; in the summer, Piłsudski’s father again requested that his son be moved to Vladivostok.

November - December

The OIAK Steering Committee commissioned Piłsudski to gather materials on the Nivkh people, paying him 200 rubles for this purpose.

1899

February

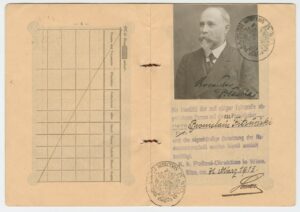

Bronisław Piłsudski was given permission to stay for a year, under police supervision, in Vladivostok, where he moved in mid-March. He worked as a curator at the OIAK (Amur Krai Research Society) Museum, with an annual salary of 600 rubles.

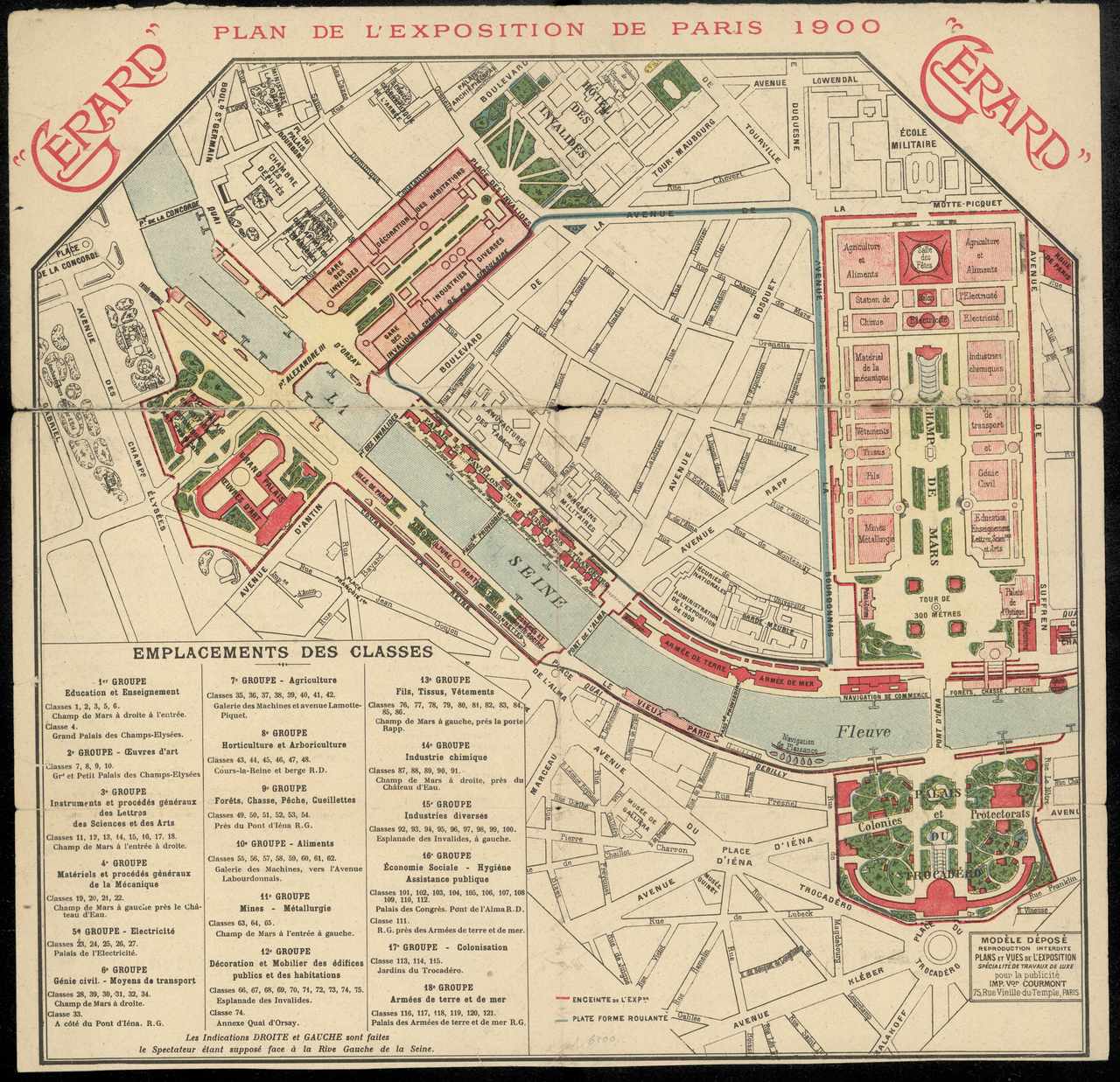

On behalf of the OIAK Museum, Piłsudski prepared materials for the World Exposition in Paris in 1900. Among other things, he presented 158 items related to the Nivkh people of Sakhalin, which he collected during his research work.

1900

Bronisław Piłsudski was awarded a silver medal at the Paris Exposition for his presentation of the Far Eastern collection; the medal has failed to reach him.

March

He cut his annual salary in half to hire for the remaining amount a worker to take care of the items collected at the museum.

1901

He signed an employment contract with the Statistical Committee of the Primorsky Krai, becoming actively involved in its activities.

March

Bronisław Piłsudski wrote to Anton Chekhov asking for a copy of his book The Island: A Journey to Sakhalin; the writer sent him the work.

Piłsudski was elected an associate member of the OIAK.

May

He resigned from his job at the museum.

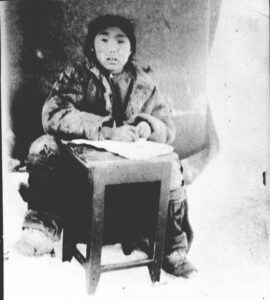

In the summer, Piłsudski brought from Sakhalin to Vladivostok his brightest student, Indin, a Nivkh boy, to allow him to continue his education.

September

The OIAK Museum again employed Piłsudski temporarily with a monthly salary of 50 rubles.

1902

February

Piłsudski received an official order to go to the southern Sakhalin to collect ethnographic materials. The governor of the Primorsky Krai wrote to the Sakhalin governor, “No objections as to Piłsudski’s behavior, he is employed by the local administration.”

15 April

Bronisław’s father, Józef Piłsudski, died at the age of 69 in St. Petersburg.

5 July

Piłsudski sailed from Vladivostok to Sakhalin on the steam ship “Zeya” owned by the Central Eastern Railway Company, presumably accompanied by Indin who was ill with tuberculosis, and was intended to be treated on his home island.

Piłsudski’s task was to collect ethnographic materials on the Ainu and Orok (now referred to as Uilta) peoples; he was issued a travel permit, 1,000 rubles for trip-related expenses, and 50 rubles for prepayments to purchase items for the OIAK Steering Committee, a camera, and an Edison phonograph.

11 July

Piłsudski arrived in Korsakov (former Japanese name was Ōdomari).

13 July

Piłsudski visited the village of Siyantsy (former Japanese name: Ochiai, now Dolinsk).

16 July - 6 August

He stayed on the west coast in Mauka District (former Japanese name: Maoka, now Kholmsk), carried out a census of the Ainu people and recorded Ainu songs with a phonograph.

August

Piłsudski sailed to Korsakov via Hakodate where he stayed for three weeks at the villa of George Denbigh (Dembi in Russian), an entrepreneur undertaking businesses in Mauka on Sakhalin); he toured the town and the surrounding area guided by his host’s son and a married couple, Mr. and Mrs. Moritaka. It was his first stay in Japan.

30 August

Piłsudski returned from Hakodate to Korsakov.

10 or 12 September

Piłsudski had an informal meeting with the governor of Sakhalin, M.N. Lyapunov. They discussed the possibility of conducting a census of indigenous peoples in the areas where he was carrying out his ethnographic research. Piłsudski appeared to be an ideal person to conduct the census due to his knowledge of both the Nivkh and Ainu languages.

Second half of September

Piłsudski visited villages of Otosan (Odasamu, now Firsovo) and Seraroko (Syeraroko, Shirer in Japanese, now Vzmorye) and participated in the Bear Festival (iomante) for the first time.

It was probably then that he first met Chūsamma, his future partner and the mother of his two children.

14–24 November

Piłsudski visited villages of Siyantsy and Otosan and organized literacy schools in both villages (formally opened in the winter). In the first school, the teacher was the 18-year-old Indin and in the second – 27-year-old Taronji (Tarōji Sentoku).

24 November

Bronisław Piłsudski stayed in the village of Rure (Rorei in Japanese) on the east coast where he recorded oral tales, songs, and legends, and made the first recordings of hauki (songs about heroes).

December

Piłsudski moved to the village of Ai (Aihama in Japanese), which was later consolidated with other villages into Shirahama, and spent the winter there, living in a Russian style log hut owned by Bafunke (Aikichi Kimura), a well known personality among Sakhalin’s Ainu people. Bafunke’s house henceforth became a permanent base for the ethnographer; Chūsamma, the daughter of Sirekua, Bafunke’s older brother, often stayed there.

1903

At the beginning of the year, Bronisław Piłsudski received a telegram from Sternberg who asked him to continue his research in southern Sakhalin. Piłsudski received funding for this purpose from the Russian Committee for Research on Central and East Asia. The first subsidy was 700 rubles for the year 1903, the second was 750 rubles for 1904, and the third was 1,000 rubles for 1905. The research was interrupted in June 1905.

1 February - 29 April

Piłsudski stayed in the Ai village for three months, where he intensively studied the Ainu language; during this period, he spent half a month (15 February – 1 March) in the Rure village, where he translated legends and hauki. It was probably then that he fell in love with Bafunke’s niece, Chūsamma. In literature, she is sometimes mistakenly called Shinkinchō by Japanese authors.

February - April

Health condition of Indin, who suffered from tuberculosis, deteriorated significantly and the young man died in a hospital in Korsakov.

24 April

Bronisław Piłsudski drafted a report on the activities of literacy schools in villages of Siyantsy and Otosan during the winter of 1902/1903.

30 April - 16 May

Piłsudski sailed along the east coast toward the south, visiting Obusaki (Fusaki), Ochkhohpoka (Ochkhikai, now Rusnoye), Tunaycha (Tonnai, now Okhotskoye), Airupo (Airō, now Svobodnaya) along the way. In the village of Tunaycha, he made recordings of hauki and oina (songs about gods) performed by Yasunosuke Yamabe and others.

Photographs of Ainu people; from the collection of the Ethnographic Museum in Kraków

June

For research purposes, Piłsudski sets off towards Hakodate on Hokkaido in the company of the Japanese translator, Tarōji Sentoku; his main piece of equipment was an Edison phonograph.

Around 8-10 July

Piłsudski arrived at the port of Hakodate where the research team of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society was formed (Wacław Sieroszewski – team leader, Bronisław Piłsudski – team member, Sentoku – translator) and prepared a research plan.

Around 2 August

Piłsudski helped the Ainu people that he met in Hakodate, cheated by a Japanese man, to return home to Shiraoi, supporting them with the money that was intended for his research. These were Shpanram Nomura (Shiran Nomurart) from Shiraoi with his family. As the result, the research team first visited the Shiraoi village, east of Hakodate, rather than northeast and north of the island, as they originally intended.

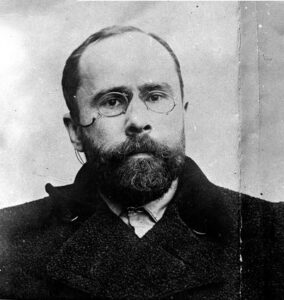

August

On the “Higomaru” ship, the team reached the port of Muroran, from where they traveled by rail to Shiraoi and then to the village of the Ainu people. They lived in Shpanram’s house as his guests until the end of August, conducting their research. A detailed description of the stay in Shiraoi and of the life and culture of the Ainu people would later be included by Wacław Sieroszewski in his book Among the Hairy People (Warszawa 1938).

The end of August

The research team traveled to Biratori (or Piratori) by rail to Hayakita where they hired a guide and several horses. They traveled through the virgin forests of Hidaka region on horseback, stopping for a night in Mukawa. The distance to Biratori was 60 kilometers in total – 30 kilometers from Shiraoi to Mukawa and another 30 kilometers from Mukawa to Biratori. In Mukawa, at the behest of the British Pastor John Batchelor (1854-1944) of Sapporo, they were met by Ainu Protestants who, influenced by Batchelor, joined the Presbyterian Church.

Early September

After arriving in Biratori, they stayed there for about a week. At the behest of the Russian consul in Hakodate, the team interrupted its research due to the increasingly deteriorating Japanese-Russian relations.

Around 10 September

The research team traveled to Sapporo.

12–15 September

The team resides in Sapporo for about 2-3 days. Piłsudski stayed at the home of the missionary John Batchelor who noted this fact in a chapter of his autobiography in the article “A Rare Visitor is Coming.”

15 September

The team left Sapporo; Piłsudski and Sentoku went to Hakodate.

19 September

The research team of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society disbanded; Piłsudski and Sentoku stayed in Japan for about 2 more weeks and then returned to Korsakov in Sakhalin.

28 September

Unofficially, the governor of Alexandrovsk, Mikhail N. Lapunov asked for conducting a study on the current situation of the Ainu people in the Korsakov District and preparing a project to improve the legislation on the governance of natives.

29 September

Return to the base in the Ai village.

The end of September

The wedding ceremony of Bronisław Piłsudski and Chūsamma initiated by Bafunke, Chūsamma’s uncle.

14 October - 29 November

Stay in Korsakovo, collecting donations, school supplies, and books for the literacy school starting its operation in Naibuchi. Von Bunge, the acting governor, supported the project with 200 rubles. Piłsudski arrived in Naibuchi on 29 November.

2 December

Tarōji Sentoku worked as a teacher at the boarding school; Piłsudski was also engaged in teaching which involved writing statements in Ainu language by using the Cyrillic alphabet. This is how the written Ainu language was created. It was the transcript of the Ainu language used by Sentoku and other Ainu people when exchanging correspondence with Piłsudski during his stay in Japan in 1906.

18–20 December

In the village of Ai, Piłsudski and his students watched a fox sacrifice ritual (literally “sending back the spirit” – iomante), prepared together with Bafunke.

1904

21 January

The Imperial Russian Geographical Society awarded Bronisław Piłsudski a silver medal for extraordinary contributions to scientific research.

Collections of Piłsudski and Sieroszewski are now kept, among other locations, at the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Kunstkamera.

8 February

At the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War, the school and dormitory in Naibuchi was closed.

12 February

Chūsamma gave birth to Piłsudski’s first child, his son Sukezō Kimura.

31 marca – 13 listopada

Piłsudski resumed the expedition to northern Sakhalin that had been interrupted in June of the previous year (despite the ongoing war). He set out by a dog sled from the Ai village and headed north along the east coast to reach the northernmost village of Nayoro (Nairo in Japanese, now Gastello); the next day, on 5 April, he arrived at the Tikhmenevsk (Shisuka in Japanese, now Poronaysk) guardhouse in the Lake Tarayka area.

6 April 6 - 12 June

Piłsudski stopped in the vicinity of Tarayka and conducted research among the Ainu and Orok peoples. He also stayed in the Nayoro village (22 April – 4 May and 22 May – 1 June).

8–30 July

Józef Piłsudski, Bronisław’s younger brother, stayed in Tokyo together with Tytus Filipowicz as part of the secret operation “Evening”. Józef intended to organize military units, searching in the Russian army for Poles who became prisoners in the Russo-Japanese War to send them to the Manchurian front; he discussed this project unsuccessfully with the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs and General Staff.

13 June - 7 October

Bronisław Piłsudski continued his research; he traveled by boat from Tikhmenevsk up the Poronay River, and then by land to areas in the upper reaches of the Tym River, and visited the Nivkh settlements located in the nearby river valley, where he conducted research (13 July – 9 August). He also stopped in the village of Onor in the Timovsk District, inhabited by Russians (24 June – 8 July and 2-25 September), and in Rykovskoye village (10 August – 1 September).

August

In Rykovskoye, he drafted a report on the activities of the literacy school in Naibuchi in the 1903/1904 season.

One of the gifts given by the Japanese consulate to the schools founded by Bronisław was the so-called brick tea.

28–29 September

In the lower reaches of the Poronay River, he experienced a violent typhoon; the swollen river capsized the boat, but Piłsudski avoided death.

7 October

Piłsudski stayed in the village of Nayoro. Because of the war, his plans to participate in the Bear Festival and opening the literacy school for the Ainu children of Nayoro and the Orok (Uilta) children of Tikhmenevsk did not come to fruition.

13 November

Bronisław Piłsudski returned to his family in the village of Ai.

16 November

He left for Korsakov where he was working intensively. Due to the difficult economic situation – hunger and price hikes – he decided not to carry out the research he planned on the west coast. Probably then he decided to leave Sakhalin and settle on the mainland.

The end of November

Piłsudski visited Otosan and Seraroko, and attended the Bear Festival there.

1905

27 January - 9 February

Piłsudski visited Siyantsy, Naibuchi, Ai, and Otosan.

10–23 February

Piłsudski’s last stay in Korsakov; in view of the approaching war and in anticipation of the Japanese invasion, he put things in order: shipped the collected ethnographic materials and secured them properly, translated the recorded texts, collected statistical data, paid the manufacturers for the materials, etc.

At the same time, violent unrest was already underway in Russia, leading to the revolution across the country, including in the Russian Far East.

23–26 February

Piłsudski stayed in Vladimirovka (Toyohara in Japanese, now Yuzhno Sakhalinsk) struggling to get food for the trip.

5 March

In the village, he met with his wife Chūsamma and son Sukezō; presumably he bid them farewell, planning to return and take his family with him in the future.

6 March

In the Otosan village, a shaman who was Piłsudski’s friend, performed a parting ritual for him.

10–28 March

With problems, Bronisław Piłsudski arrived in the Onor village, where he finished the “Draft Principles of the Existence and Governance of the Ainu of the Sakhalin Island” commissioned by the Governor Mikhail N. Lyapunov. This was a novel concept of self-government of ethnic minorities.

13 April - 12 May

Piłsudski stayed in the village of Rykovskoye; he completed writing the following works: “Some Information on Individual Ainu Settlements on the Sakhalin Island” and a modification of the “Draft Principles of the Existence and Governance of the Ainu on the Sakhalin Island”, which he submitted to Governor Lyapunov, as well as a report on literacy education, carried out in the winter of 1904/1905.

30 April

The final end of serving a sentence depriving Piłsudski of his civil rights – he was allowed to settle anywhere in the Russian Empire, excluding the capital; he could also return to his home country.

12–30 May

Piłsudski stayed in the village of Derbinskoye (now Tymovskoye).

11 June

Piłsudski left Sakhalin on a ship departing from the port of Alexandrovsk.

12 June

Piłsudski arrived in Nikolaevsk at the mouth of the Amur River, and stayed there for about 10 days. On his way to Khabarovsk, he visited Mariinskoye (inhabited by Olcha / Mangun people) and gathered information about the Ainu living in the Amur River region.

The early July

He arrived in Khabarovsk.

14 July

Piłsudski completed the report on the current situation, written for V. Radlov, the Chairman of the Russian Committee for Central and East Asian Studies.

Early August

He returned to Vladivostok.

5 and 12 August

Piłsudski (as an associate member of the OIAK) gave two lectures on the results of his research in Sakhalin carried under the auspices of the OIAK.

5 September

A peace treaty between Japan and Russia was signed in Portsmouth.

Middle of September

Piłsudski planned to return to Europe with his family by rail and made efforts to get tickets, which he did not receive. After the land transport system collapsed, he changed his plans and wanted to return by ship. He visited the Ai village (already under Japanese occupation) and met with his family, Chūsamma and Sukezō. However, Chūsamma’s family did not agree to Piłsudski’s wife and his son leaving; as a result, Bronisław separated from his family forever – as it would turn out.

Early October

Piłsudski visited Kobe, where he provided help in the office of Nicholas Russel (Nikolai Sudzilovsky).

November

Piłsudski returned to Nikolayevsk on the Amur River. Commissioned by the OIAK, he collected materials on the Nanai people in the village of Troitskoye in the Amur River basin.

5 November

At the meeting of residents of the city of Khabarovsk, Piłsudski delivered a speech, proposed the establishment of a “civic office”, and donated 100 rubles for this purpose.

8 December

Piłsudski’s daughter, Kyo Kimura (who changed her name to Ōtani after marriage), was born in the Ai village.

18 December

Bronisław Piłsudski sailed from Vladivostok toward Japan, leaving Russia forever.

1906

Early January

Piłsudski arrived in Tokyo.

Around 6 January

Bronisław Piłsudski gave an interview to the reporter of “Hōchi Shimbun” newspaper (in article: “Two Rare Visitors from Vladivostok; ”Hōchi Shimbun”, 7 January); reprinted in: “The Hokkaido Times”, 10 January. He lived in the Central Hotel in Tsukiji.

The last decade of January - the first decade of July

Piłsudski lived on the second floor at the back of Hakodateya in Owarichō, in the Kyōbashi district. While in Tokyo, he maintained close contacts with researchers studying the life of the Ainu people, socialists, women’s rights activists, artists, and Chinese revolutionaries associated with Minpōsha, such as Huang Xing and Song Jiaoren, as well as with refugees from Russia. He wrote articles: “Russian Anthropologists” (“Tōkyō Asahi Shimbun”, 8 February), “Research on Japanese Women” (“Hōchi Shimbun”, 9 March), and “Foreigners’ Research on Japanese Women” (“Hokkai Times”, 20 March).

Together with Shimei Futabatei, he established the Polish-Japanese Association with the goal of popularizing the knowledge of Polish literature in Japan.

Around 18 June

Commemorative photo with Shimei Futabatei at the Nakaguro Photo Studio in Hongō

June

Piłsudski received 500-600 rubles, transferred by his relatives by telegraph via Paris to Nagasaki, for his return trip to Poland. However, he could not collect the money in Nagasaki and eventually, was able to get it in Kraków, at the place it was originally sent from.

July

Piłsudski left Tokyo and went to Nagasaki, where he lived in the house of Chikatomo Shiga (an employee of the Russian consulate) in the Inasa district.

10 July

The first article on the Ainu people, “The Situation of the Ainu People on Sakhalin” (Part 1), was published in Japanese (translated by Masaru Ueda) by the monthly magazine “World” (“Sekai”, no. 26) of the Keikanippōsha Publishing House; it was the first part of the publication titled “Some Information on Individual Ainu Settlements on the Sakhalin Island.”

30 July 30 - around 16 August

Bronisław Piłsudski left Nagasaki; he departed on the “Dakota” ship owned by the American Great Northern Steamship Company, sailed through Kobe, Yokohama, and across the Pacific Ocean straight to Seattle. On the ship, he worked extensively; he published the second part of “The Situation of the Ainu People on Sakhalin” (“Sekai”, no. 27).

Around 16 August - around 21 October

After “Dakota” arrived in Seattle, Piłsudski continued his journey by the transcontinental railroad to the east of the United States and arrived in New York City via Chicago, from where he reached Europe via the Atlantic Ocean; then he arrived in Kraków via London and Paris.

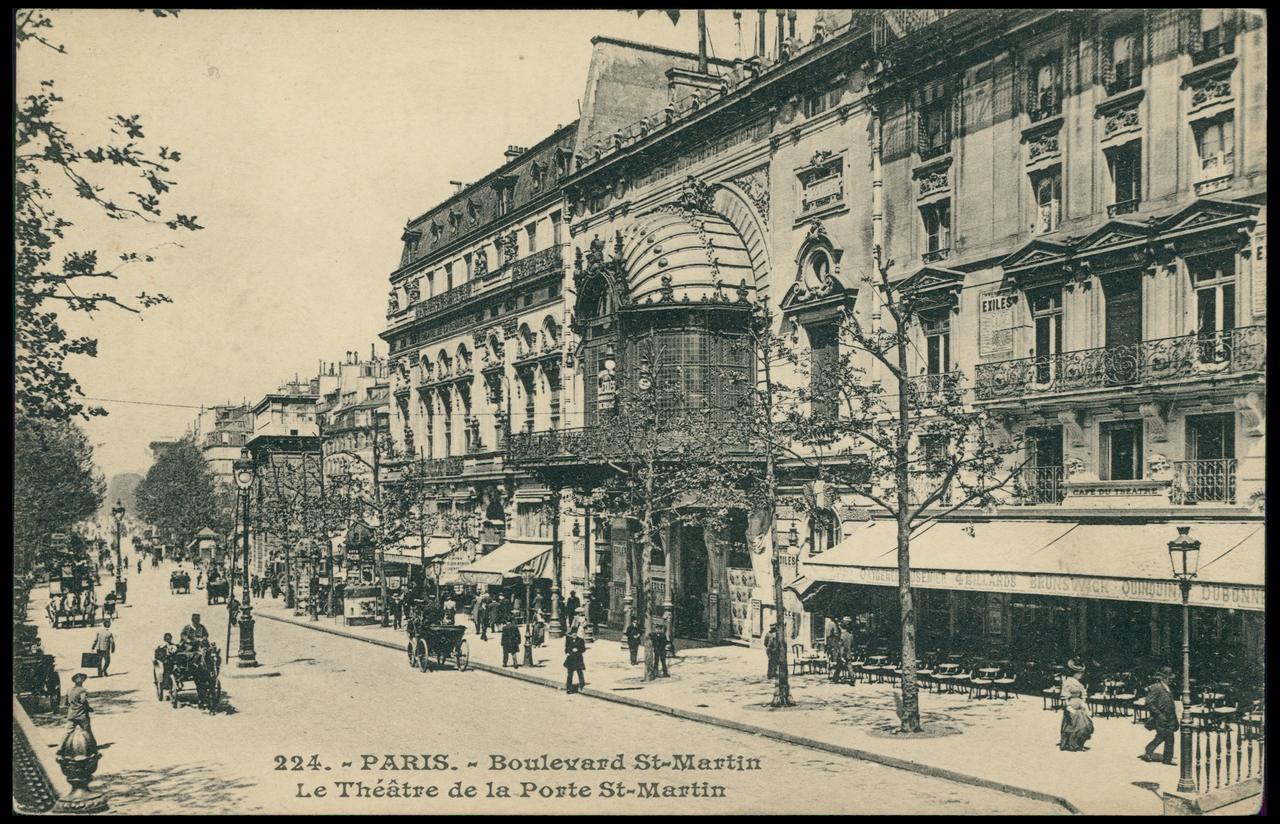

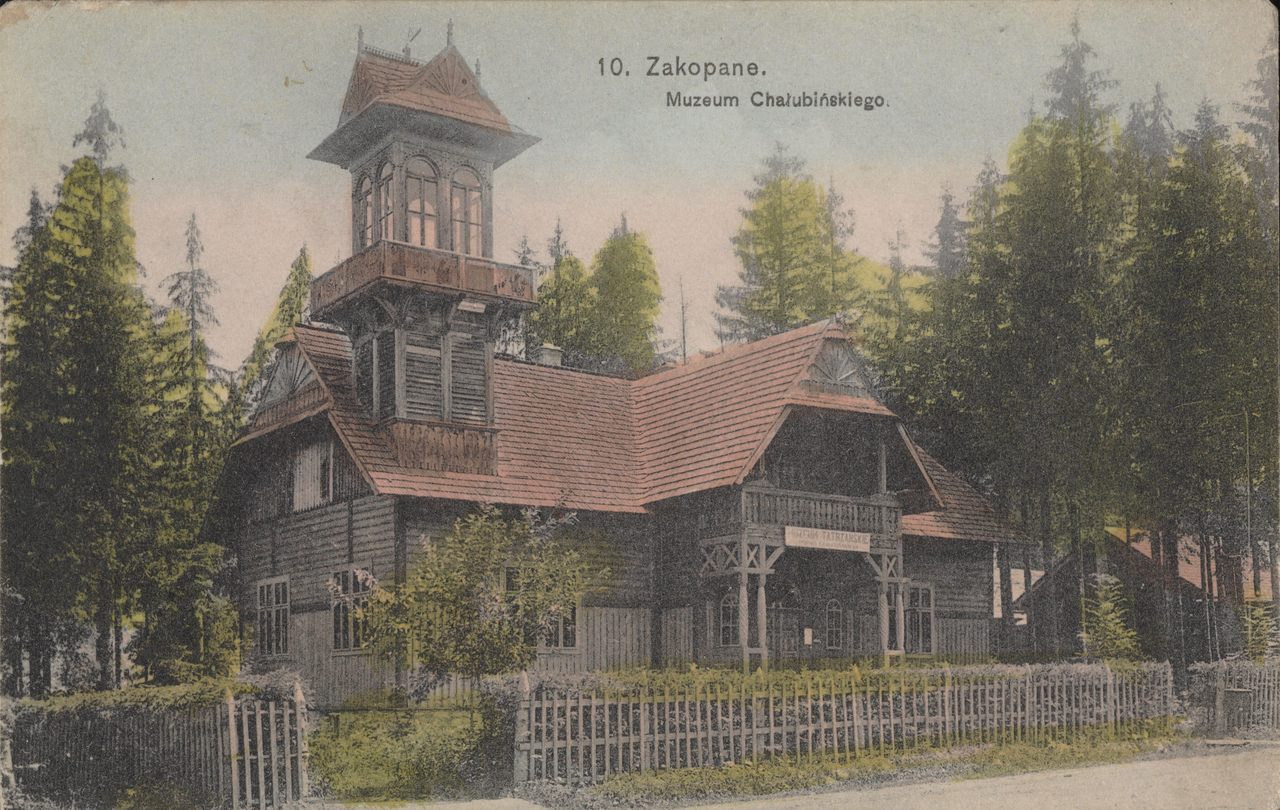

Around 21 October

Piłsudski arrived in Kraków and then left for Zakopane, where his younger brother Józef was staying; this was their first meeting in nineteen years.

Excerpt from Józef’s letter to Bronisław staying in Paris:

Dear Broniś! Finally! At last you are so close to me – when you will read this letter, I no longer have any patience. […] Address, Zakopane, Nowatorska Hyc Olesiak Piłsudska and the other address, Topolowa 16, Kraków, Piłsudska. […] my dear and precious, please hurry and don’t waste time, I’m waiting for you, you are terribly late…

7 November

Piłsudski returned to Kraków, where he stayed until May the following year.

20 November

Pursuant to the pardon decree of 21 October 1905, the governor of Sakhalin announced that the police supervision and the restriction of the right to settle in the capital were lifted for Piłsudski and also informed of the decision to restore Piłsudski’s rights and privileges lost as a result of court proceedings. Piłsudski regained the right to inherit the land and property owned by the Piłsudski family; he could also reside in Russia’s capital.

21 November

In a letter to Shimei Futabatei, there is a mention of Maria Żarnowska (née Baniewicz, a younger sister of Bronisław’s first love, Zofia Baniewicz). Maria Żarnowska separated from her husband, with whom she left their only son at their home in St. Petersburg.

During the Christmas holidays, Bronisław Piłsudski was visited by his youngest sister, Ludwika, who lived in Vilnius, and his aunt Stefania Lippman.

At the end of the year, at Bronisław’s request, his younger brother Kazimierz, who lived in St. Petersburg, forwarded in a letter to Żarnowska Bronisław’s address.

1907

17 May

Maria Żarnowska arrived in Kraków, where she met with Bronisław Piłsudski for the first time in 20 years.

Early June - second half of July

Piłsudski and Żarnowska stayed in a Czech resort, Karlovy Vary (then Karlsbad).

August

Piłsudski returned to Cracow and then to Zakopane, where he lived for the next eight months. Bronisław and Maria initially stayed at a hostel for students and since November, they lived at the “Villa Hygea” guesthouse at the Krupówki Street.

Relations between Piłsudski and Witkiewicz

“My Dearest Uncle”

Relationship of Bronisław Piłsudski with Stanisław Witkiewicz

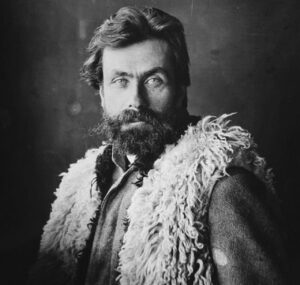

The two Piłsudski brothers met for the first time in nineteen years in October 1906. It took place in Zakopane, where Bronisław arrived at Józef’s invitation immediately after returning from many years of exile and settlement in the Far East. Over the next eight years, Galicia became the ethnographer’s new home to which he used to return from longer and shorter journeys.

He spent the first two weeks resting with his brother and his wife Maria. From here and later from Kraków, he wrote letters and shared his feelings with his sister. “Dear Zuleczka, here I am finally […] among my beloved. I find it strange but it’s true – my new life to which I rushed and dreamed of has already begun. Still, it’s not this sincere homeland here like our Lithuania […], but it’s at least Europe. It is Poland”. He announced about his return to his respected professor and ex-exile Benedykt Dybowski, and also to Futabateia Shimei from Japan to whom he pointed out his readiness to start his work.

At the turn of October and November, Bronisław visited the Tatra Museum, which had been operating in Zakopane for seven years. At that time, it was located in a wooden, two-story building equipped with a small tower of meteorological observatory and two rooms with natural and sightseeing exhibits. With time, the need for a new premises emerged.

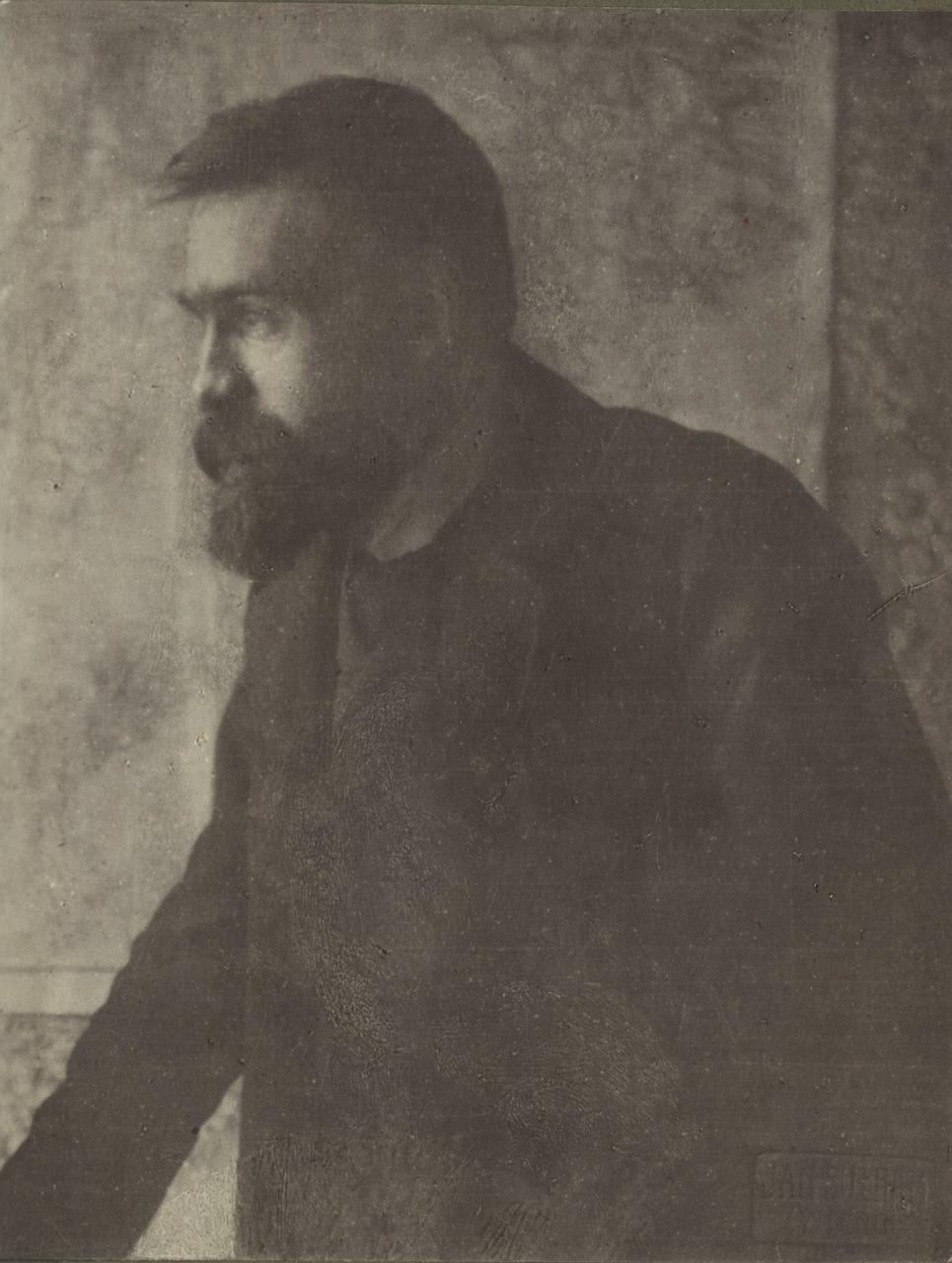

Bronisław Piłsudski’s photographs taken by Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz-Witkacy in Zakopane in 1912; from the collection of the Józef Piłsudski Museum in Sulejówek

Witkacy also painted a portrait of his “dearest uncle”, which is known only from the photo attached to his correspondence with his father, Stanisław Witkiewicz.

At the end of the 19th century, Zakopane experienced a spontaneous growth as a place of treatment for “chest diseases”, thanks to the promotion of its values by Tytus Chałubiński, a doctor from Warszawa. It attracted Polish intellectual elites from the three partitions, but mainly from Kraków, Lviv and Warszawa. The main tone of the cultural life was set by the artists who settled there, especially Stanisław Witkiewicz. Attracted by examples of curing tuberculosis, he visited this place in 1886, and after four years, he settled there permanently. In 1908, he moved to Lovran, where he died seven years later.

In the first weeks of his stay in Zakopane, Bronisław Piłsudski managed to meet Stanisław Witkiewicz. The families of Witkiewicz and Piłsudski were probably related to each other. Many authors have tried to unravel the problem of their kinship. The words of an expert on Lithuanian affairs, Stanisław Cat-Mackiewicz may serve as conclusion, “All landowning families in Lithuania are related and all were patriotic exalted.” In any case, conviction of family ties cultivated on both sides made the relationships much easier. Later, in letters to Stanisław Witkiewicz, Bronisław used to call him “Dear Uncle” (it was only 15 years gap between them), and signed himself as a “nephew.” The son of Stanisław, Witkacy, titled Bronisław in a similar way.

At that time, Stanisław Witkiewicz was an undisputed authority in matters of the Podhale highlanders’ region. Bronisław recalled that the reading On a Saddle: Impressions and Images from the Tatras by Witkiewicz (published by Gebethner and Wolff in Kraków in 1890) inspired him to become more interested in the folklore of Podhale. The creator of the Zakopane style realized that the “nephew” had extensive knowledge and skills in the field of ethnography, so he was one of the people who persuaded him to undertake research on Polish highlanders living not only in southwestern Galicia, but also Spisz, then on the Hungarian side, and Orava. While carrying out projects in this area, Bronisław could rely on the support and convenience resulting from the authority of his “uncle”. Witkiewicz wrote to the Tatra Museum Society, “I authorize Mr. Bronisław Piłsudski to use the fund provided by Mrs. Włodzimierzowa, Count Dzieduszycka, for the purchase at his discretion objects of Podhale art, equipment, clothes, etc. to expand the collection of the Tytus Chałubiński Tatra Museum in Zakopane “.

The cooperation and exchange of views between Piłsudski and Witkiewicz continued also when the latter moved to Lovran. This is evidenced by Bronisław’s letters (published in 2016 by the Tatra Museum in Zakopane and the Józef Piłsudski Museum in Sulejówek) to his “Dearest Uncle”, in which he reports on his achievements and shares his observations about museum buildings he saw in Russia, Japan, the United States, and European countries. Thanks to these comments, the designer of the Tatra Museum building could have a broader view on this issue. Letters addressed to Bronisław have not been found.

Inspired by Witkiewicz, Piłsudski developed a multifaceted and useful activity in the Southern Borderlands. Many of his ideas, consulted by correspondence with his “Uncle” in the years 1912-1914, were implemented by his successors, including founding a scientific periodical. The adopted by the Tatra Museum “Podhale Yearbook” , which is issued to this day, is one of the most interesting regional publications in our country. The first issue with Bronisław Piłsudski’s article is available here:

The ties between Bronisław Piłsudski and Podhale are commemorated by a symbolic grave erected in 2000 at the “Pęksowy Brzyzek” Cemetery of Merit in Zakopane, next to the grave of Stanisław Witkiewicz, his “Dearest Uncle”.

Based on:

Antoni Kuczyński, red., „Kochany wujaszku. Listy Bronisława Piłsudskiego do Stanisława Witkiewicza”, Zakopane – Sulejówek 2016

Jerzy M. Roszkowski, „Witkiewiczowie – Piłsudscy. Wzajemne związki”, „Rocznik Podhalański”, tom XI: 2016, s.87-99

Summer

The four Piłsudski brothers held a family conference in the Tatra Mountains; it was attended by Jan with his wife Maria who came from Vilnius, Józef with his wife Maria, Kazimierz from St. Petersburg, and Bronisław with his partner Maria.

22 October

Maria Żarnowska left Zakopane and returned to St. Petersburg. Bronisław Piłsudski wrote her many letters; in one of them, he offered her to start a life together in Lviv.

In that year, the “Review of the Economic Life of the Ainu People on Sakhalin” and “Some Information on Individual Ainu Settlements on the Sakhalin Island” were published in Vladivostok.

1908

Second half of January

Maria Żarnowska returned to Zakopane; they both lived in the “Villa Hygea” guesthouse.

March

Bronisław Piłsudski and Maria Żarnowska moved to Lviv where they lived at Turecka Street 3. Piłsudski sold eight phonograph cylinders from the Ainu collection and several photographs. This was undoubtedly one of the happiest periods of his life. He collaborated with Benedykt Dybowski, with whom he exchanged letters while on Sakhalin. Żarnowska took singing lessons as she dreamed of a career as a professional singer. She stopped her lessons due to illness – breast cancer.

1909

Spring

Maria Żarnowska returned to St. Petersburg to undergo a surgery, during which metastases were found.

August 1909 - January 1911

Piłsudski traveled across Europe, working as a correspondent for the leading Lviv daily “Kurier Lwowski”; he carried with him Ainu handicrafts and cylinders with recordings of their folklore texts which he intended to sell.

November 1909 - May 1911

Piłsudski stayed in Paris. He frequently changed his place of residence (mostly in the Latin Quarter). He visited libraries and probably attended lectures at the Sorbonne. He spent time in the company of Polish intellectuals, including Maria Skłodowska-Curie.

1910

February

Piłsudski arrived in Kraków and took Maria Żarnowska with him to Paris to undergo radiation therapy.

April

Maria Żarnowska’s condition worsened and another surgery became necessary. Żarnowska left Paris of her own accord; her husband, with whom she had been separated until then, took her back to his home and provided care.

Early June

Piłsudski visited London. At the Japanese-British Exhibition, he met Ainu people from the Saru Valley (4 men, 4 women, and children) who were demonstrating a model of the Ainu village; he interviewed them and took notes of more than 50 stories. He also sold several Ainu handicraft items and cylinders.

1911

End of January

Piłsudski returned to Kraków (via Paris), where he lived at 31 Szlak Street (in his brother’s Józef apartment).

April

In Limanowa, he visited a former prisoner on Sakhalin, Edmund Płoski, whom he had met in Aleksandrovsk shortly after his arrival there.

12 May

Maria Żarnowska died in St. Petersburg.

20 September

Bronisław Piłsudski, invited by Count Władysław Zamoyski, lived in the School of Women’s Home Labor in Kuźnice, in room 4 above the soap store.

It was there that he prepared his most important book for publication Materials for the Study of the Ainu Language and Folklore, edited by Prof. Jan Rozwadowski of the Academy of Sciences in Kraków.

25 November

In the hall of the Zakopane Falcon Club, on Piłsudski’s initiative, the Folklore Study Section of the Tatra Society was established, and its statute and program were adopted. Bronisław Piłsudski was elected its chairman. The Section’s headquarters were located in the Tatra Manor. Piłsudski planned to hold a new exhibition at the Tatra Museum to present the artifacts he had collected.

AdomasVarnas (1879-1979), one of the Lithuania’s most prominent painters, made Piłsudski’s portrait in the Ainu costume at Stefan Żeromski’s home. In conversations with the painter, Bronisław discussed the issue of the so-called Lithuanian crosses, on which he himself would write a document in 1916. Varnas created a photo album.

1912

Middle of April

Piłsudski moved to “Korniłowiczówka”, the home of his friend Tadeusz Korniłowicz in Bystre, at Droga do Jaszczurówki 2 (now Oswalda Balzera 4). He lived there until the end of his stay in Zakopane. Oktawia and Adam Żeromski also lived in this house, and sometimes Stefan Żeromski. Thirty years later, it was in the attic of this house that the cylinders were found, which Piłsudski had left there. During this year, Żeromski made Bronisław one of the heroes of the short story titled Beauty of Life and named him Gustaw Bezmian.

October

Bronisław Piłsudski left for Prague to visit museums. He probably also visited Martin in Slovakia and Vinohrady in Bohemia.

December

Piłsudski stayed briefly in Kraków and Zakopane, and then left for Neuchâtel in Switzerland in order to begin regular ethnological studies.

Before leaving, he unexpectedly submitted his resignation from the position of chairman of the Folklore Study Section, but it was not accepted; Piłsudski ended up continuing to perform his duties through letters sent from abroad.

The Academy of Arts and Sciences in Kraków published the main article titled “Materials for the Study of the Ainu Language and Folklore.”

In Zakopane, Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (Witkacy) painted on glass Piłsudski’s portrait against the background of Podhale (it was lost, only this photograph exists).

1913

3–5 January

Piłsudski became a student at the University of Neuchâtel.

Beginning of May - 10 July

Piłsudski stayed in Paris.

25 June

Piłsudski used the signature “Ginet-Piłsudski” for the first time in his letter to the Tatra Society. The Ginet family is descended from the Lithuanian Grand Ducal Dynasty – and Piłsudski family is descended from this family; his last name was recorded as “Ginet-Piłsudski.” Piłsudski saw himself as a liaison between Lithuania and Poland.

10 July - October

Piłsudski stayed in Brussels, Belgium; he worked at the Solvay Institute.

3 August

A new exhibition was opened at the Tatra Museum in Zakopane; Piłsudski, who was then in Brussels, did not attend it.

October

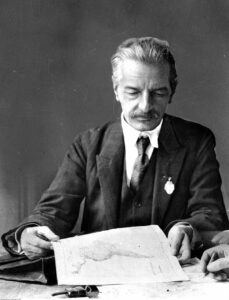

Piłsudski returned to Bystre in Zakopane and as the chairman of the Folklore Study Section he worked intensively on the organization and the program of the local history and research group; its operation would later be expanded to the regions of Orawa and Spisz. He was also active as an executive employee of the Tatra Society and a head of the editorial board of the newly established magazine “Rocznik Podhalański”.

1914

March

The Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences in Kraków established the Ethnographic Committee and appointed Piłsudski its secretary. He received a salary of 600 krone a year for his work and was the only salaried employee on the Committee. This was his first permanent job and a steady annual income since his arrival in Europe seven years earlier.

He completed editorial work for the first issue of the “Rocznik Podhalański” magazine, which would eventually be published in 1921; the “Introduction” included a memoir of Bronisław by Wacław Sieroszewski.

End of June

A visit to Brussels.

5 August

The beginning of World War I.

Beginning of December

Piłsudski left for Vienna (according to the order of the Kraków authorities, he was not allowed to stay in the city threatened by a Russian attack, much less that he did not have a passport), where he lived at Schindlergasse 44. He would stay there for more than four months, until April next year.

He was involved in the work on the Polish Encyclopedia, the purpose of which was to acquaint the world with facts about Poland that did not exist as a sovereign country on the maps. Researchers in Vienna, Warszawa, and Lausanne worked independently on the Polish Encyclopedia. Piłsudski undertook to combine the results of their work.

Work on the Polish Encyclopedia

With the outbreak of World War I, Bronisław joined the stream of peaceful actions to regain independence. Together with other Poles who left the war-torn Galicia, he found himself in Vienna. There, in the fall of 1914, under the tutelage of Bishop Władysław Bandurski, the idea of preparing a work entitled “Poland. A Thing about its Past and Future” arose. Awareness of the importance of this undertaking absorbed Bronisław who played an important role in the first stage of its implementation.