Pedagogy

Bronisław Piłsudski as a Pioneer of the Education of the Indigenous Inhabitants of Sakhalin

Activities

Piłsudski’s teaching activities started during his stay in the village of Rykovskoye, in the first period of his exile. In addition to his work in the prison office, he engaged there in meteorological observations and – not without a sense of pride (as he mentioned in a letter to L.J. Sternberg) – in teaching and educational activities.

“At my place in the village of Rykovskoye, folk readings were organized, albeit not without difficulty; it can be clearly seen that they are accepted and provide satisfaction and benefits, especially from the fact that about 100 people or more gather each time. […] We read short stories by N. Gogol (Taras Bulba – this single story was illustrated), Kulak by N. Nikitin, The Murmuring Forest by V. Korolenko. [The initials of the names were completed by A.K. and W.Ł.]. Now we have received historical maps from Alexandrovsk and are teaching how to use them along with a systematic lecture on Russian history. The second part of the lecture is always devoted to fiction books.”

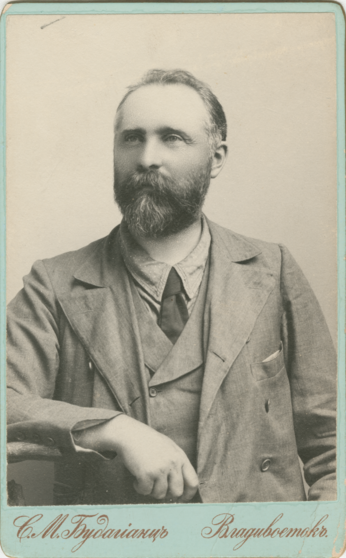

Photo from the collection of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences

Multiple documents have been preserved that prove conclusively the strong involvement of B. Piłsudski in the development of educational institutions on Sakhalin. For example, in his letter to the head of the district, G.V. Savrimovich, he formulated a clear project for “the development of folk education and its organization in the Timovsk District.” In another letter to the aforementioned L.J. Sternberg, he wrote, “I consider myself incapable of educational activity because I can’t establish discipline, and if I ever manage to influence someone, it’s only through cordial conversation, but even this requires mutual sympathy and sufficient authority of the teacher.” When looking closer at B. Piłsudski’s teaching work, it should be clearly emphasized that he used this “mutual sympathy” and “mutual affection” as a base for his great authority in the community of Sakhalin’s inhabitants. Even during the first period of his stay on Sakhalin between 1887 and 1899, he made plans for the development of teaching work and wanted to give it an institutional form. This is because he understood the need to educate the indigenous tribes so that they would not fall behind the Russians and the Japanese. He saw education, among other things, as an opportunity to raise the social status of the islanders. He wrote about this in the article, which can be successfully called a memorandum, entitled “Nuzhdy i potryebnosti sakhalinskikh gilyakov” [The Situation and Needs of Sakhalin’s Gilyaks], which was published in 1898 in Khabarovsk.

“The ability of primitive peoples to adopt cultures of civilized races is confirmed

by numerous examples. Wherever such peoples were approached with the intent

to share with them the achievements of civilization, successful results were

obtained. One should not resort to violence, but rather influence them with

persuasion, humanitarian attitudes, gentleness, and leniency.”

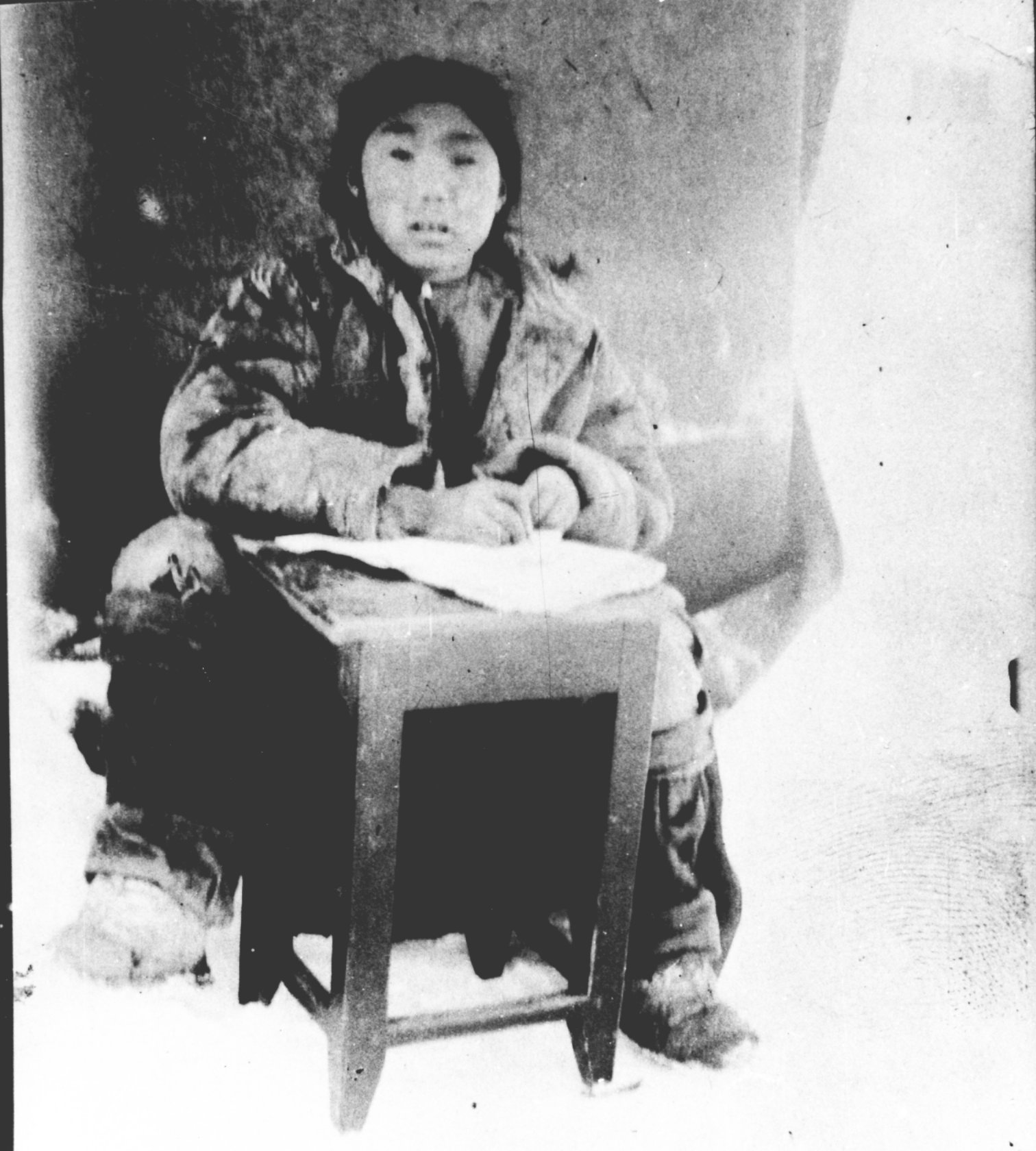

The views thus formulated found practical expression in his daily dealings with the natives; therefore, Bronisław Piłsudski became very famous in their settlements. Much could be written about this, because until recently, there were still some elderly people living in Nivkh villages who knew from family accounts the humanitarian activities of this extraordinary man. Bronisław Piłsudski’s educational intentions were focused on training over time the teachers recruited from among the natives themselves. For example, on his trip to Vladivostok in 1899, B. Piłsudski took along Indin, a Nivkh boy, with the intention of educating him so that he could teach his fellow tribesmen upon his return to the island.

This noble intention failed, as the boy died a short time later, leaving Bronisław Piłsudski in deep sorrow. On the other hand, Piłsudski was successful in working with a young Ainu man named Tarōji Sentoku who assisted Piłsudski and Wacław Sieroszewski during their expedition to Hokkaido, thanks to whom the efforts to establish schools for the Ainu people brought more concrete results, especially in terms of teaching. In the source materials concerning Bronisław Piłsudski, one can find passages that directly describe his educational work among the peoples of Sakhalin. These include numerous articles, photographs, letters, personal notes, accounts, and official reports. For example, quite recently two manuscripts were found in the Central National Far East Archive in Tomsk, bearing the following titles: “A Brief Preliminary Report on the Ainu School in the Korsakovsky District in 1903-1904” and “A Brief Report on the Ainu Elementary School in the Korsakovsky District in 1904-1905”. The documents were first published in Polish by A. Kuczyński and V. Latyshev in 1993.

Photo from the collection of the Ethnographic Museum in Kraków

The published documents disclose many details about this project and show Piłsudski as its initiator, deeply convinced as to the need to educate the natives. When the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War interrupted the successful work on establishing elementary schools for the Ainu children, Piłsudski was convinced that when life there returned to its peaceful and slow pace, the Ainu people’s aspiration for education and the quickest possible organization of schools would take an even fuller form… What was needed, of course, was a considerable amount of money for this purpose and people. The money should have been provided by the state and the people should have been anticipated from the Russian public, always sympathetic to good projects.

Bronisław Piłsudski’s plans to provide universal education of indigenous children on Sakhalin were successful when he personally oversaw their implementation. However, from his biography we know that in 1905, he left Sakhalin forever. Soon the southern part of the island came under Japanese rule. The Japanese government imposed its own rules on education. Many Ainus were resettled in Hokkaido, where the process of their acculturation began. Indigenous groups living in the northern part of Sakhalin, which remained under Russian rule, lost their advocate. The work started by Piłsudski was not resumed for many years. However, many of the thoughts and recommendations made by B. Piłsudski in the first years of the 20th century have not lost any of their relevance.

Based on:

Antoni Kuczyński, Vladislav Latyshev, “On the Pedagogical Activities of Bronisław Piłsudski (presentation of sources)”, Etnografia Polska, vol. XXXVII: 1993, book 2