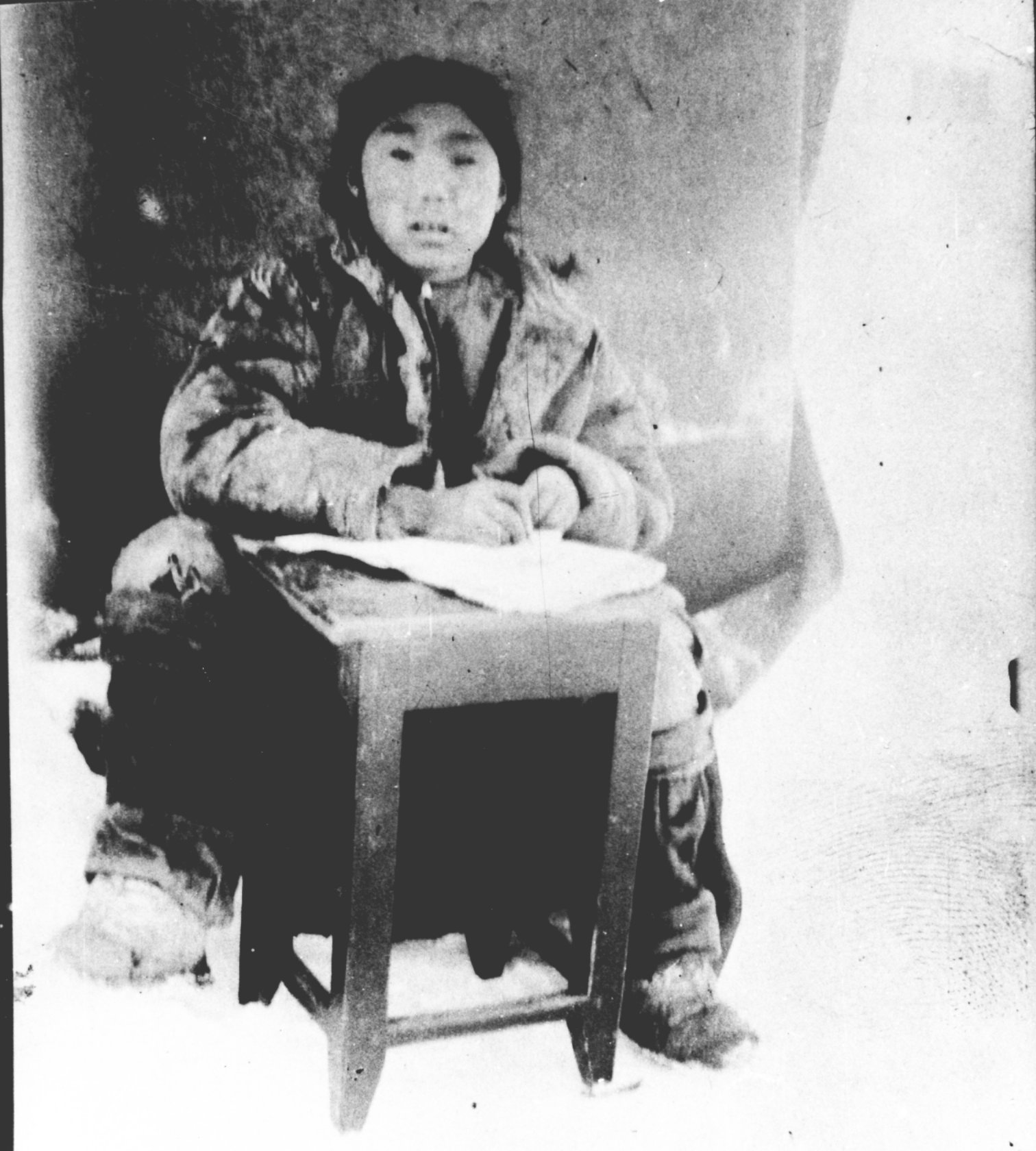

Pedagogy

A Brief Report on the Ainu Elementary School in the Korsakovsky District in 1904-1905

Activities

In the fall of 1904, I wanted to start teaching Ainu children in the village of Nayero, as I intended to stay there for a longer period of time, roughly until mid-winter. I was informed about their willingness to learn by several youngsters from Nayero and Tarayka back in the spring. I would also like to attract the children of the Oroks, who live in the Tikhmenevsky settlement, to attend the school.

I planned to bring the teacher Tarondzi from the village of Naybuchi in the south, because I knew that classes at the school would not start anyway without me. I also waited for teaching aids from the south, because when I left the Tymovsky District, I managed to get only one copy of the reading book.

For the time being, I moved into the caretaker’s room in the village of Nayero in anticipation of the arrival of the teacher from the south and the Oroks from the north after they finish hunting, and I suggested to the Ainus eager to start learning that they should come to me. So far, four boys – 12-16 years old youngsters – have appeared. The oldest quickly gave up, because it was difficult for him to learn figures and numbers, and his family also complained that two people from one family had been separated from home for too long.

Slowly but quite systematically, almost every day, we taught reading from just one book, as well as writing, and arithmetic that was the most easily learned by the Ainus. The boys were eager to learn, although the cramped space, constant hustle and bustle in one room of the caretaker’s apartment, and lack of teaching aids were of a hindrance; even pencils were not available and sometimes we had to write with small scraps (stubs). There was even more general grief when I decided to leave for the south earlier than I planned. The Bear Festival in the village of Nayero, which I had previously hoped for, was postponed until next year. And in the south, on the contrary, celebrations of tracking five bears were planned. Many Ainus from Nayero rushed there on boats. I also wanted to take the opportunity to once again participate in this major Ainu holiday, and on 1 November I left, abandoning sad children and the education they had just begun.

The teacher did not show up. The Oroks also did not arrive and the whole action plan failed. I asked the caretaker to show the letters and numbers to the children from time to time. But this did not work out. The military surgeon from Nayero then took one boy, an orphan, and began to teach him, but after a few days, the elders returned and took the boy away. In the south, I witnessed the same mood and conditions that, back in the spring, forced me to finish classes in the school earlier than planned.

Rumors of the expected landing of the Japanese circulated widely, almost every day smoke from ships [was seen] here or there. The ludicrous talk of the Ainus knowing when and where the landing would begin was reaching them here as well. On the one hand, they believed that the Japanese would occupy the island, and on the other hand, they were terribly afraid of the moment of landing and the resulting fight for the island. What to do? Where to go? Danger is caused not only by stray bullets; military troops caused no less fear in the Ainus than vagabonds, highwaymen; some, for the sake of their wives, would not want to meet the Japanese military. There were also rumors that after seizing Sakhalin, the Japanese would deport the Russians, and them as Russian subjects. One senior and important Ainu dignitary said that I had a special objective to luring all Ainus to Russia. In case the Japanese came, many were preparing to flee to the mountains. Each family tried to be together in these difficult, threatening moments, and just as they had insisted on discharging their children from the boarding school in the spring, they were now afraid to send them back to school. I suppose that the fear of displeasing those whom the Ainus believed to be the possible new future rulers of the island also had an impact. The hatred of some Japanese, characterized by chauvinistic attitudes toward Russians, was known to the Ainus all too well.

Once, back in 1903, one Ainu said that it was bad for children from only one settlement to be taught. If it was then disapproved of, the consequences would be borne by fellow residents. Therefore, it would be better to teach one child from each settlement. It is very possible that one of the Japanese expressed discontent with our school, comparing it to those beautiful mission and government schools that were organized on the island of Hokkaido for the Ainu people living there.

From time to time, there were rumors in the settlement that the Ainu students would be conscripted, that they had already taken away all students somewhere on the Amur where the Golds were taught. It was only natural that such rumors would affect the parents of the students. “Don’t get angry,” said one Ainu, a friend of mine, “that I don’t educate my son, but when there is such terrible uncertainty about whether we will live tomorrow, to tell the truth, I don’t care if my son dies literate or not.” A boarding school and more efficient organization of teaching, that is running a school in one place, and with my direct participation, were out of the question. Even the room that was used last year was not available. Soldiers were stationing in Naibuchi and new reinforcements were constantly sent there. Despite such conditions, I didn’t want to abandon the classes. After all, it is known that without continuous exercise, people who can barely read and write quickly forget their knowledge. That’s why I persuaded the teacher Tarondzi to agree to work a little in the current year, touring those settlements where those natives who were already learning lived, in order to make them read, write, and count, as much as the local conditions allowed. At the same time, I instructed him not to refuse to help those who wanted to start learning.

And if previously our classes were far from the ideal organization of work, now they have turned into repetition courses for those who already know how to read and write a little – the semi-literates. In addition to Tarondzi, who agreed to tour the settlements of Rure, Naibuchi, Ay, Otosan, and Seraroko, one of the older students, 18-years old Tuichino, more capable than the others, started teaching children in his settlement of Siyantsy. An acquaintance, a well-educated exile from the nearby settlement of Nikolaevsk, promised to help him.

On the other hand, dropping in from Korsakovo twice, I saw these classes conducted extremely improperly, slowly, sluggishly – as it could be assumed – and without the enthusiasm, tact, or didacticism indispensable to educators. My teachers had only one necessary quality for an indigenous school educator – the knowledge of the students’ native language, in which alone anything can be explained to them.

No clear progress had been made by the children by the time I left. Of all the students, only six boys read printed text in Russian, albeit with difficulty, and it is easier for them to write Ainu words in the Russian alphabet; as for arithmetic, they know the first three operations. Nine students have not yet completed their learning, and in arithmetic some of them know only addition and subtraction, others – only addition.

When leaving on 20 February, I asked Mr. Verzhbents, the supervisor of the 2nd section, always sympathetic to the teaching of Ainu boys, and A.I. Ivanovna, a female teacher from the village of Vladimirovka, to visit and encourage teachers and students. Due to the above circumstances, I did not ask for money for the school. As you can see from the account presented, I didn’t even spend the money I had left over from the previous year. I had 76 rubles and 85 kopeck left. I spent 43 r. and 05 k. out of that amount (namely: for teachers until 20 February 1905 – 40 r., and for stationery – 3 r. 05 k.). I forwarded 28 rubles to the overseer of the settlements with a request to pay the teachers if they continue teaching. I kept 5 rubles 80 k. myself, hoping to get any books or games suitable for the students, and send them as school gifts.

This winter, a gift from only one person was received. Mrs. Jakobson donated four dozen black pencils, five colored pencils, and two quires of writing paper (24 sheets). Now, in these turbulent, uncertain times, the hand is not used to write in more detail about the wishes regarding the Ainu schools on Sakhalin. However, experience has shown that there is a willingness to learn. I firmly believe that as life here is peaceful and calm again, the pursuit of learning will express itself in a stronger form. To meet this apparent movement among the Ainus to free themselves from the continued inertia and passivity, and move closer to the cultured races, no small amount of money and people are obviously needed. Money should be secured by the state, and people can be anticipated from the Russian society, which is always open to useful initiatives and good undertakings.

Every beginning requires outstanding workers, people dedicated to their work, and the natives of Sakhalin who, due to events unfortunate for them, over decades, have become acquainted with the outcasts of normal society – the unfortunate but strongly spoiled exile element – have more right than anyone else to receive better, more valuable people, and deportations should be abandoned.

As for the type of schools that easily take root among the natives and are beneficial to them, I have written about it elsewhere (“Governance of the Ainus of the Sakhalin Island”).

In addition to documents on the disbursement of money, I am also presenting examples of written work of Ainu student boys.

28 April 1905, Rykovskoye settlement, B. Piłsudski

It would also be appropriate to mention the beginning of teaching of Ainu children in Mauka.

I first met the Ainus when I arrived in Mauka in the summer of 1902. I was surprised by the extremely large number of people learning in Japanese. Several young people who already knew how to write were my guides, and they jotted down Russian words that were new to them in a notebook using Japanese characters. In the houses of Ainu teachers, I was founding Japanese laborers or scriveners from neighboring craftsmen’s workshops focused on classes. A conscious pursuit of education was evident in them. So I advised the elderly people to ask the local administration to open a school in their settlements, explaining that the school would be Russian, of course, but the privileges of an educated person (no matter what language) were the same. I submitted such an application and it was approved by the Chief War Governor of the island. He even instructed to try to get a room for the school by asking industrialist Dembi who had fish processing plants on Sakhalin. In the spring of 1903, the latter promised to fulfill this request if I undertake to manage the school. Unfortunately, my research activities on the east coast of the island, and therefore trips to Japan and the Oroks, did not allow me to take advantage of this offer. However, I felt some remorse for the Ainus of Mauka who, being less influenced by the crude newcomers and much influenced by the Japanese, were more motivated to learn than the Ainus of the eastern shore of Sakhalin. Despite these dilemmas, we could not find a suitable teacher to run this school.

When in the spring of 1903 Dr. Kirylov passed through Korsakovo to Mauka to take up the position of a doctor at the place of industrialists Semenov and Dembi, I informed him about the conditions that could ensure the establishment of a school. He promised me that he would try to join in promoting Russian education in the village. In June, he wrote to me that he “could not organize the school during the summer season, but he would try to get it started for the winter.” There were 12 children in that school, then 7, and 4 of them were Ainu children. After that, I didn’t hear from him anymore.

In the autumn of 1903, I learned that Semenov and Dembi’s trusted man – the bankrupt bookseller Zenzinov known to me from Vladivostok – had gone to Mauka, and that he was in charge of continuing the education of those children who had started with Dr. Kirylov. I wrote a letter to Zenzinov, asking for detailed information about the school, results of teaching, and needs concerning school supplies.

The reply I received, dated 31 December 1903, was the following: “The school in Mauka is located where it was previously when Dr. Kirylov was in charge (of course, in one of the mine buildings owned by Semenov and Dembi), and is heated every day. With my cooperation with a Japanese carpenter, we made long school tables and benches, a black board, and a classroom abacus. Classes began on 30 November and are held every day except holidays from 9 – 11 AM. There were 8 Ainu students and 4 of them learned with Kirylov. They hardly know how to read and 4 of them were starting their education. All the children were 8-10 years old. We work on the alphabet using the sound method, with the help of the movable alphabet left by Dr. Kirylov.

As for the children of the Russians, I vouch for their progress, and as for the children of the Ainus, I can’t say anything concrete for now just because they do not go to school systematically, as their parents send them to different activities. The main reason, however, is their lack of knowledge of the Russian language. It is possible to achieve relatively quick results in reading, but it is mechanical. Without knowing Russian, they read – but understand nothing. Therefore, they are not interested in reading and they leave school on their own, so it is doubtful whether they will continue to engage in reading. Well, this main reason makes you think about how all of this could be avoided.

The Ainu people here are more influenced by the Japanese than by the Russians. All children speak Japanese better than Russian, so Russian educators who do not know Japanese and Ainu languages will not succeed in Ainu schools.”

After the declaration of war, Mr. Zenzinov left Mauka, and classes with the children were discontinued.

For the 1904-1905 school year – 76 rubles and 85 kopeck was not spent.

Amounts spent:

25 November 1904, for stationery products – 3 r., 05 k.

30 December 1904, Tuychino, for teaching children in summer – 3 r.

20 January 1905, Tarondzi, for teaching from 20 December to 20 January – 12 r.

20 January 1905, Tuychino, for teaching – 8 r.

20 February 1905, Tuychino, for teaching from 20 January to 20 February – 5 r.

20 February 1905, Tarondzi, for teaching from 20 January to 20 February – 12 r.

Total – 43 r. 05 k.

Left to the chief overseer of the settlements for teachers’ expenses – 28 r.

Grand total – 71 r. 05 k.

The amount not spent – 5 r. 80 k.

28 April 1905, B. Piłsudski

[Translated from Russian by Antoni Kuczyński, translated from Polish by Piotr Jaskólski]

The documents presented here reveal yet another area, not at all insignificant for the needs of Sakhalin: B. Piłsudski’s humanitarian and social activities. They expand the knowledge of this outstanding man, whose teaching activities on the distant island enrich the pages of our educational history. Even these reports on the activities of elementary schools prove conclusively that his view of education was innovative for that time, which certainly needs no comment.

From the quoted reports found by V. Latyshev, a picture emerges of the personality of Piłsudski who was capable of acting for the “good of others.” This ideal humanist did not divide people into better and worse, and provided everyone with his care regardless of their religion or skin color. In addition to these numerous virtues, he was also tolerant towards religion and did not share the view of the Russians living on the island that a “good native” is a native baptized in the Orthodox faith. Thanks to this attitude toward people, B. Piłsudski enjoyed great moral authority among the Sakhalin community, which was not without influence on his achievements in the research on the indigenous culture. There are few materials today that document B. Piłsudski’s activities on this remote “prison island,” which is why the information contained in the school reports presented here is all the more valuable; it expands our knowledge about his life and creative efforts he made for the benefit of the indigenous communities where he happened to live during the long years of his exile.

Based on:

Antoni Kuczyński, Vladislav Latyshev, “On the Pedagogical Activities of Bronisław Piłsudski (presentation of sources),” Etnografia Polska, vol. XXXVII: 1993, book 2