Activities

The Legacy of Bronisław Piłsudski’s Achievements and the Identity of Smaller Nations

Activities

As a pioneer in the field of documenting endangered cultures, Piłsudski left a great legacy that not only protects the heritage of smaller nations, but also influences contemporary approach to the issue of their identity. His research work, particularly in the context of the Ainu people, has contributed to the preservation of their unique culture and identity.

Nowadays, much attention is paid to the issues of globalization, national identity, problems of little homelands, acculturation of the nation’s heritage, and ethnic policies, i.e. problems that arise in multinational states. There are bodies striving to protect the language and culture of numerous national minorities and ethnic groups. It’s not really a new issue, what can be proved by documents and legislative activities taking place as early as the 19th century.

Despite legal regulations, many indigenous groups ceased to exist, others have lost their ethnic distinctiveness, language or culture. This state of things has survived and even if some actions are being taken towards “returning to the roots” or “ethnic awakening”, they do not bring the desired result. There are many examples of small indigenous groups of great Siberia, for which the sense of ethnic belonging is now something distant or disappearing. Sometimes, 90% of an ethnic community of up to 1,000 people does not speak their language (e.g. the Yukhagirs or Itelmens).

But there are also positive examples. After the fall of the Soviet Union, behind the Ural Mountains, the efforts were made to protect the language and culture of the indigenous ethnic minorities living in these vast areas. Among the Buryats, Khakas, Yakuts, Koriaks, Nenets or Nivkhs, who emphasize their relationship with their own region, giving them a sense of being at home and among their own, a kind of new ethos is born with a whole system of coherent ventures that have a collective value for these communities – their own language, culture, religion, and traditions.

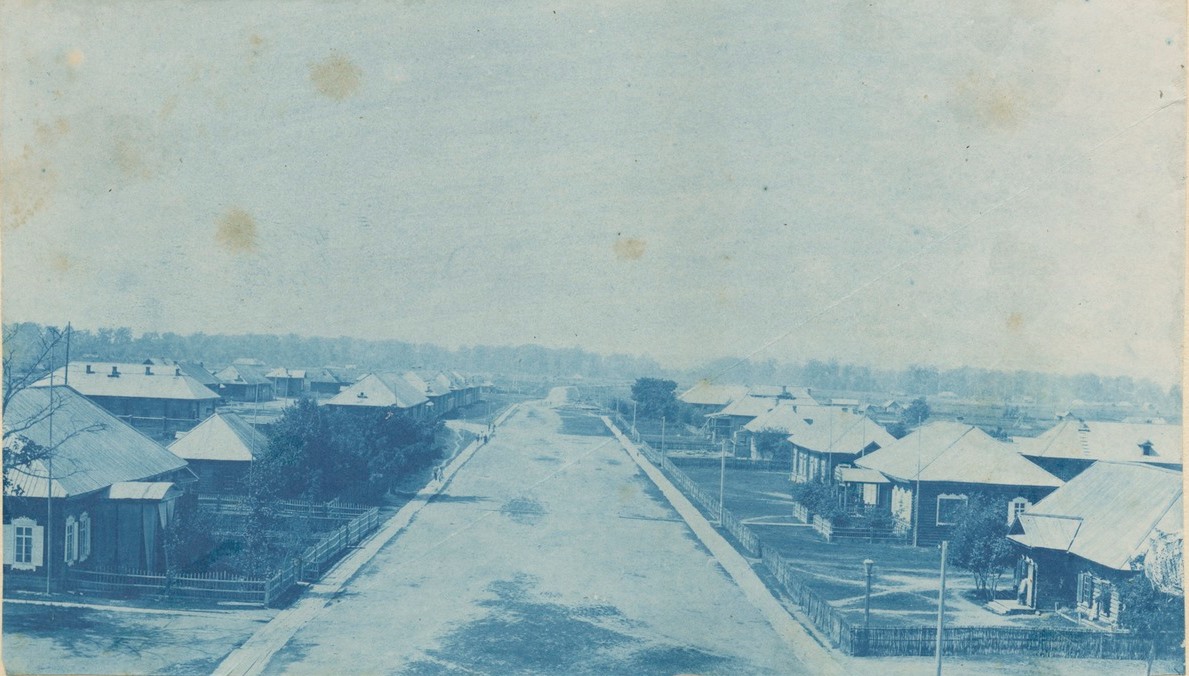

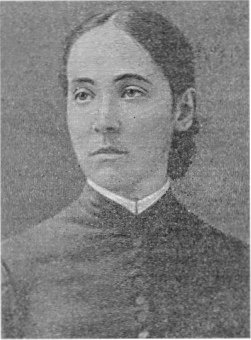

The ethnic linguistic and cultural communities of Sakhalin were the subject of Bronisław Piłsudski’s research. His stay on exile became a source of creating meaningful opinions in different fields connected with the study of indigenous culture: ethnology, linguistics, religious studies, folklore studies, physical anthropology and ethnogenesis. In his publications on various aspects of the culture of the Ainus, Nivkhs and Oroks, we can find passages clearly indicating his deep attention to these peoples, to their hospitality, culture and also misfortunes resulting from the colonization of Sakhalin by the Russians. These texts also show the natives’ reciprocated sympathy that was a fruit of long-term relations, when Bronisław could learn the secrets of their culture. It was his way to study their beliefs, rituals, songs, fairy tales, and legends. The Nivkhs’ sympathy for the researcher can be clearly perceived in the songs dedicated to him, and composed by native women. In these songs he was called a brother, friend, and defender. And he wrote as follows:

“The first I met when I came to Sakhalin by blind fate, were the Giliacs. It was them that have remained forever my best and dear friends of shared misery. The days of fame and times of the great past for the entire tribe are gone, from their point of view, and will never come back… And they, the recent lords of the mountains rising everywhere, of the swift, clear, and ever-murmuring streams and rivers, of the dense and mysterious forests full of animals with thick furs, proud of their dominion over the vast nature, were trampled by the newcomers, losing forever the freedom they loved so much.”

Even after leaving Sakhalin, he did not stop thinking about these issues, so in 1909, he concluded his lecture at “The Société d’Anthropologie de Paris” with these words:

“Let me keep you, Gentlemen, for a while to share my thought that has often haunted me during my stay among the children of nature. We study every detail of their past, but we don’t care for their future at all. They are going extinct; they are disappearing […]. At present, they are quickly losing their own individuality due to destructive encounter with the invaders. I lived among them, and I read a sense of the near end in their sad eyes. These people are instinctively looking for support from anyone who will show them a little favour.

As a man belonging to a nation which is also suffering, I have felt their deep depression. It’s my moral duty to draw attention of interested scientists to the fate of the primitive races. I have no doubt that the French Society of Anthropology, the first that began the study of man, which also gave birth to so many great and noble ideas, will take the initiative in directing all good intentions and will strive to care for these abandoned beings. It’s our duty, arising from the feeling of humanity, and it’s an act of rescue that must be attempted.”

Piłsudski’s work played a role in the preservation and documentation of the national identity of peoples who were threatened by colonialism and imperialism. His experiences as a Pole whose own national identity was threatened by the policy of Russification, may have influenced his sensitivity to the cultural problems of other nations. In the preface to Materials for the Study of the Ainu Language and Folklore, he compared the situation of the natives pressured from an alien civilization to his own – a prisoner who spent his early youth in a country under foreign occupation. Here is what he wrote:

“(I spent more than 18 years in the Far East, but not by choice.) Not ceasing to dream of returning to my homeland, I was trying as much as possible to get rid of the burdensome awareness that I was banished and found myself in the yoke of slavery, detached from everything that was priceless to me. That’s why I’m in natural way inclined towards the natives of Sakhalin, the only people here who had a sincere attachment to this country that has been their place of living since time immemorial, who were hated by people establishing a penal colony here. By relating to these children of nature who were put in extremely hard situation by the intrusion of a completely different form of civilization, I have understood that I use a specific strength and elicit gratitude although I do not have any rights. (Since my student years spent in Wilno in those gloomy times, when we were persecuted at school in order to root out the national history and culture, when we were forced to speak the language of the invader, I have been trying to live and act in such a way as not to be classified to the hated people who violate the rights of individuals and nations). […] It gave me pleasure to bring joy and hope for a better future to these tribesmen who were concerned about the burdens of life they still experienced. The sincere laughter of children playing, tears of emotion in the eyes of good women, a smile of gratitude on the face of a sick man, shouts of appreciation, or just a pleasant pat on the shoulder – all these were like a balm soothing my fate.”

Owing to Piłsudski’s natural, friendly, helpful and humane attitude, the native inhabitants of Sakhalin placed the full trust in him too. The military governor of Sakhalin took advantage of this by asking Bronisław to develop a draft of the rules for administering the indigenous tribes of Sakhalin, and to examine the demographic and economic situation of these tribes.

After reviewing various instructions and laws regulating economic, social, and ethnic issues in the vast territory of Siberia by the central authorities in St. Petersburg in 1899, the Ministry of Internal Affairs considered them obsolete and requiring modification. Hence, in 1900, ordinances were issued obliging governors to develop a “draft law on the natives.” When the central authorities demanded providing these materials, it turned out that the relevant offices in Sakhalin did not perform this task. These were the times when Japan was clearly interested in Sakhalin, so it was in the interest of the Russian authorities to improve the rules of administration of the island, and to amend the laws concerning the natives. In consequence, Piłsudski’s mission based on collecting ethnographic materials about the Ainu and Orok peoples, was expanded to include a draft of administration principles and a census. His works in the future became the basis for further research and activities for the protection of these cultures.