Ethnography

Travel Path of Bronisław Piłsudski in his Research on the Ainu People

Activities

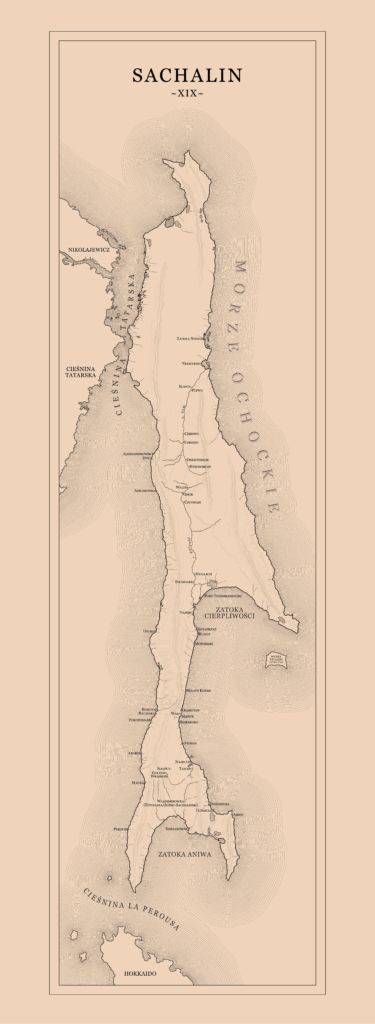

At this point, it should be noted that geographical names on Sakhalin underwent many changes in the 20th century. The names of not only towns and villages, but also rivers and mountains changed depending on who ruled the island: Russians or Japanese; they were radically changed by the Soviet government and after the political changes of the late 20th century, the old Russian names were partly restored. In addition to them, there were names given to places by the indigenous peoples. Consequently, in order to follow Piłsudski’s route on Sakhalin based on his descriptions, it is necessary to compare it with old maps from the late 19th century. Nothing could be more confusing than a search for old names on modern maps; for example, the Naibuchi village known to Piłsudski was located on the shore of the Sea of Okhotsk which is on the eastern coast, while the modern Russian village of that name is situated several dozen kilometers west of the sea shore, in the interior of the island.

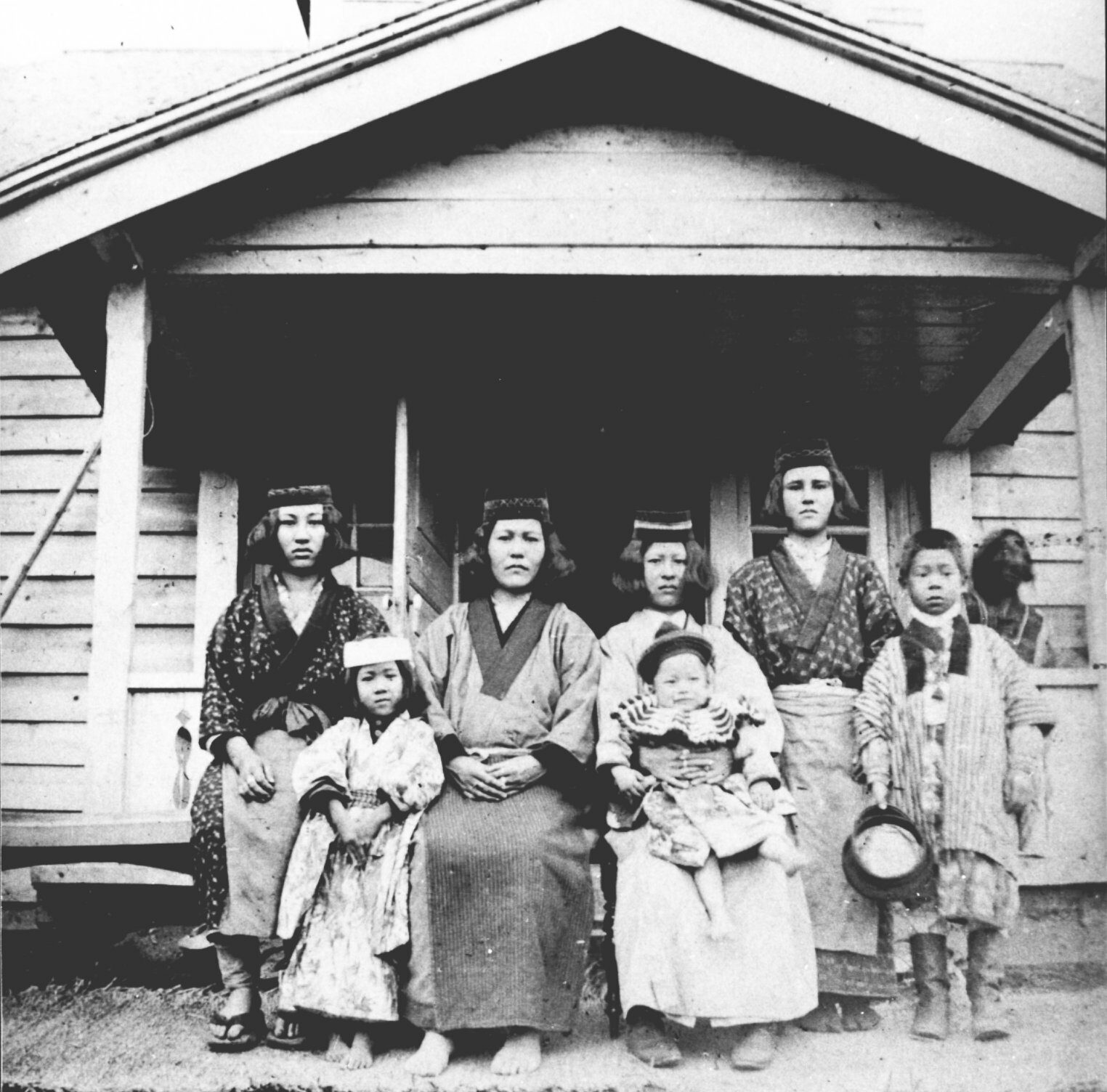

Piłsudski made his trip to meet the Ainu people as soon as he arrived on the ship “Zeya”, on which he sailed on 11 July 1902 from Vladivostok to Korsakovo (actually the Korsakovsky Post), an administration center in the very south of Sakhalin. His task was a research mission to study the Ainu people for the prestigious Imperial Russian Academy of Sciences and assemble a collection of objects of the Ainu and Orok (Uilta) peoples for the Museum of Academy of Sciences. After meetings at the office, it became clear that it would be beneficial to conduct a census of the indigenous population during the expedition, and Piłsudski obtained the relevant documents. (It is worth remembering that about several years earlier, the Russian writer Anton Chekhov used a census as similar mechanism to reach habitats and settlements in Sakhalin.)

Piłsudski made his first journey to visit the Ainu people just two days later. He went to the village of Siyantsy located about eighty kilometers northwest of Korsakovo. He managed to collect a number of artifacts there and decided to go to the western shore near the port of Mauka (Maoka in Japanese, Endunkumo or Entunkomo in Ainu, and now Kholmsk) on the western coast of Sakhalin to get more. He knew that the area around Mauka had the largest concentration of the Ainu people on the entire island. They were employed by fishing companies, both Japanese and Russian. In Mauka, Piłsudski met and befriended two enterprising and wealthy merchants from the company of Semyonov and Dembi (actually Denbigh – Richard Denbigh was Scottish), doing extensive businesses with China and Japan. They willingly provided him with a storage space for the collection and hosted Piłsudski for a time. Piłsudski used to set out on foot to many settlements where he collected various items; he also conducted a census in seventeen villages. He was aware that the Ainu population varied greatly depending on whether they lived in the west coast (north or south) or the east coast (mainly south) of Sakhalin. He was preparing for an extended stay in order to study all the characteristic groups and was looking for a way to get to the east coast. The shortest route from west to east across the island was dangerous. This was not only because it led through mountains covered by a dense primeval forest, but also in view of numerous groups of bandits (usually former prisoners who escaped from the penal colony) hiding in the mountains and making a living from robbery.

Meanwhile, it also turned out that a rapid transport of the collection by sea from Mauka to Korsakovo around Cape Crillon was impossible due to the very infrequent domestic connections on this route. The merchants Semyonov and Denbigh suggested that he should then take an indirect but safe and regularly serviced route, and use the commercial ship connections from Mauka to Hakodate on Hokkaido and from there back to Korsakovo on Sakhalin. Piłsudski used their suggestion and thus found himself in Japan for the first time in August 1902, piloting a transport of his collection on a ship. He stayed in Richard Denbigh’s magnificent villa in Hakodate.

After returning to Sakhalin at the end of August 1902, Piłsudski stayed for two weeks in Korsakovo and after shipping a part of the collection back to Russia, he prepared the next stage of his research expedition. He met with the island’s governor, General Mikhail N. Lyapunov who allowed him to use the police archives and encouraged him to continue the census. At the time, Piłsudski made a proposal to the general to organize a network of elementary schools for Ainu children, offering his personal supervision and training some Ainu and Nivkh people he knew as instructors. One of his assistants was Indin, a Nivkh boy who had been Piłsudski’s student while he was still in Rykovskoye as a prisoner and whom Piłsudski brought to Vladivostok (when he took the position of curator at the museum) so that he could complete a few grades of education at a regular Russian school.

Now on Sakhalin, Piłsudski prepared for an extended autumn-winter stay in the Ainu settlements on the east coast. In October, he received the decision of ending his prison sentence and officially giving him the status of a “peasant” (krestianin in Russian) registered in the Tymovsk District.

During that time, Piłsudski began to learn the Ainu language and collected the necessary bibliography. He studied the only existing Ainu-Russian Dictionary by Mikhail Dobrotvorsky, published in 1875, searched for a place to stay during the winter, and looked around for the possibility of establishing a school for indigenous children. He also applied to the Academy of Sciences for an approval to extend his mission by a year. He eventually moved to the east coast and became acquainted with the residents of two villages on the coast, Sieraroko and Otosan, to which he was to return many times over. In November, he revisited two villages of Takoe and Siyantsy, where he eventually established a school for Ainu children, and the village of Rure.

He also found a great residence for himself for the winter – a log cabin built in the Russian fashion by one of the wealthiest Ainus in the village of Ai located by the sea and on an important transportation route between the south and north of the island. This location of the cabin meant that people traveling from north to south and those returning, both Ainus and Nivkhs, would eagerly come and chat with Piłsudski. The cabin was owned by Bafunke (Bahunke, Bagunke), a respected member of the Ainu community. His young niece Chūsamma became Piłsudski’s friend. Piłsudski later entered into a ceremonial marriage with her and became the father of her two children. By the winter of 1902-1903, Piłsudski already knew the Ainu language well enough to easily listen to and take notes on stories, songs, and legends dictated to him at his request. He closely observed the work, family leisure and customs, and had the rare opportunity to learn about Ainu medicine. He probably witnessed the birth of his own son, as his extremely detailed description of the ceremonies and nursing procedures concerning the birth of a child is so accurate that it must have been based on direct observation and explanations obtained later.

For two winter weeks, invited by village elders, Piłsudski stayed in the Rure settlement located by the sea. There he managed to collect twenty fairy tales and one song of the hauki – heroic genre. At the time, he tried his own, very original method of writing text (adding letters from the Latin alphabet to the Cyrillic letters, where the Cyrillic did not reflect the pronunciation well). He also attempted what he called an “interlinear” translation of texts: under each phonetically written line of text, he would enter the exact translation of the words and phrases, thus preserving their original order (sometimes absurdly unintelligible in the language of translation), and only then he would translate the line, arranging the words in the new order of the language of translation. In this way, he made it easy for him to memorize entire speech patterns, very archaic at times, with strange mental constructions and an amazing play of connotations.

He also decided to penetrate the areas toward the south coast, where Russian infiltration was the smallest. To this end, in April 1903, he and his companions sailed in an Ainu boat to the villages of Obusaki, Ochiohpoka (Ochiehpoka), Tunaicha, and Airupo (Airuno). At the time, he wrote down many valuable technical and customary notes related to herring fishing, which is the real wealth of Sakhalin’s eastern coast. It turned out that the caught herring served not only as a product for direct consumption, but also as a source of valuable oil used in the industry for spreads, as well as in animal feed. Gorbush (a type of salmon) fishing had just begun in Rure, and Piłsudski learned about the interesting superstitions and customs associated with catching of this fish.

Nevertheless, the trip, although very valuable in cognitive terms, was physically strenuous. In a report written later, Piłsudski wrote that the forced diet consisting of only rice and semi-dried Sakhalin taimen for several weeks, was very hard for him.

In April, after some rest, Piłsudski settled in Naibuchi on the coast and from there, he walked almost daily to several settlements located within a triangle with the side of six kilometers: Siyantsy, Takoye, Sakayama, and Rure. At the time, he was conducting a census for the governor and kept a close eye on the cooperation between the Ainus and the Japanese in artels, a kind of cooperatives of small manufacturers. It so happened that about a year earlier Russians had allowed the Ainus to run small cooperatives, so now Piłsudski was looking at the effectiveness of the new solutions proposed by the Russian government and was also studying the impact this new administrative form had on the lives of the Ainus. In the future, this was to prove crucial in drawing up a proposal for social self-organization among the Ainus (unfortunately, the war prevented the implementation of Piłsudski’s project).

See: Activities/Social Relationships

Piłsudski strongly felt his social instincts during conversations with the Ainus repatriated from Hokkaido after decades of forced emigration to the Ishikari region of the island who were called Tsuishikari Ainu. Since their return to Sakhalin, their status was virtually “stateless,” as they did not have Japanese citizenship and had lost their Russian citizenship by emigrating. Consequently, they could not be legally employed or obtain any assistance. Piłsudski drew attention to this problem in his report at the end of his mission.

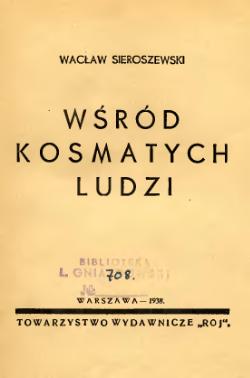

In the course of intensive work in Naibuchi, he received a letter from Wacław Sieroszewski who invited him to join an expedition for the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences, in order to study the Ainu people in Hokkaido from an anthropological perspective.

Sieroszewski, wrongly convicted of alleged involvement in the preparation of a political demonstration in 1900, had been arrested and expelled from the Congress Poland. With the support of the Russian Geographical Society, he was able to conduct an expedition to the Russian Far East in 1903-1904, and study the lives of the local peoples. In 1903, he planned an expedition to the Japanese islands to conduct research among the Ainus on Hokkaido. At Sieroszewski’s request, the Russian Imperial Geographical Society sent a petition to the governor of the Amur Krai, Governor-General Deyan Subbotich to grant permission to Bronisław Piłsudski (“a peasant registered in the Tymovsky District”) to go with Sieroszewski. The governor had to seek approval for this decision from the minister of interior himself, and received it by telegram in June.

After various problems, Piłsudski joined Sieroszewski in Hakodate on Hokkaido, a city he had already known. Wacław Sieroszewski and Bronisław Piłsudski’s expedition to Hokkaido deserves a separate description; therefore, we recommend that you read the following article:

See: Activities/Ethnography/Wacław Sieroszewski’s Expedition…

In November 1903, Piłsudski returned to Naibucha to check on the progress of students at the school he established, received additional financial support from Governor F. Bunge, and intended to open another boarding school in the village of Takoye.

Meanwhile, as early as in September 1902, an unusual opportunity arose in the village of Otosan located on the coast to participate in the biggest Ainu ceremony called iomante, which means “sending back of the spirit” of the animal to the God of the Mountains. Sometimes iomante is also called the Bear Festival.

See: Activities/Ethnography/IOMANTE / Bear Festival

Still in November, Piłsudski managed to take part in the Fox Festival (fox sacrifice – iomante) in the village of Ai, for which he himself provided previously purchased foxes, and took his students from the school in Naibuchi to this important and rare festivity.

In early January 1904, Piłsudski came to the village of Otosan, where he helped to prepare a fest of erecting ceremonial sacred rods with impaled spiral shavings called inau, which were the most distinctive visual element of Ainu religious practices.

February 1904 saw the ultimate crisis in the increasingly tense Russian-Japanese relations, and a war broke out after a sudden Japanese attack on Port Arthur. Despite Russia’s predictions and efforts, each month the balance of victory tipped toward Japan, which sought a strong foothold on the Asian continent.

The situation on Sakhalin – a place of strategic importance – was becoming more and more difficult. All inhabitants, indigenous people, Russians and Japanese, as well as prisoners of the penal colony were expecting an attack by the Japanese at any time. The Ainus, who cooperated with the Japanese in the south of the island, were judged by the Russians to be very uncertain about which side they would take. In parallel with the Russians’ preparations to evacuate to the mainland, Japan repatriated some seven hundred of its citizens to the Japanese Islands out of fear of the enemy’s military operations. The cost of living in Sakhalin was rising, the population was taking up arms, and gangs of fugitives from the penal colony were marauding in less guarded areas. In this situation, it was difficult for Piłsudski to conduct a new research, but he nevertheless did not stop working on the materials already gathered, and was collecting new ones as far as possible. In 1904, his son Sukezō (such was his Japanese name, the Ainu name is unknown) had already been born and Piłsudski had to be even more concerned about the future of his family.

The Ainu children from the school in Naibuchi had already been taken away by their parents from the dormitory. Piłsudski had already sent back almost all the items in his collection, and decided to take the rest with him when he evacuated to the north of Sakhalin. He was looking for the right route to take.

At the end of March 1904, just before dusk, he started his trip by sleigh to the north along the sea shore. He reached the small village of Vari, where he managed to rent a boat with rowers and on 3 April, with his Ainu comrades, set off on the frozen sea further north. Cold, they reached Hunup and spent a night in an empty fish warehouse. Next day, Piłsudski exchanged the rowers and continued the trip. After two days, he reached Nayoro, also located on the shore of the Sea of Okhotsk. From there, he set off again by sleigh and arrived at the Tikhmenevsky Post, where he met Russians and numerous Ainus living around the nearby Tarayka Lake.

His stay in the area of Tarayka continued for several weeks until 4 May, and was very fruitful for Piłsudski. He managed to resume his work as an ethnographer.

The Ainus and Nivkhs had just arrived at the shore of the Sea of Okhotsk for a seasonal great seal hunt. Piłsudski diligently observed the cruel hunt (with clubs to save the skin; many years later in Zakopane he told friends what the hunt was like); he observed the ritual of sending the skulls of captured seals decorated with herbs back to the God of the Seas – to the sea waves. Since he had rice in his stockpile and the Ainus did not have it, he gave some to the Ainus to make a benevolent offering to the sea in gratitude for the safety and the bountiful catch. He noted with satisfaction that at last he succeeded in reaching the northernmost Ainu settlements on Sakhalin. He hoped to find villages with inhabitants the least “tainted” by contacts with both Russians and Japanese, and he was not mistaken.

He characterized the Ainus of the Tarayka area as very brave, proud, and eager to talk about past wars waged against the Oroks. He took notes on legends of the past battles and heroes, and took photos.

See: Activities/Ethnography/ Story of an Ainu Man from Tarayka

Now Piłsudski was going to head for the mountains to the west of Tarayka as the rumor was that the bones of some huge ancient animal were found there. However, he did not manage to go. He also asked the Ainus what they knew about the legendary, archaic, and extinct Tonch people, traces of whom remained in the form of ruins of dugouts and pieces of clay pots.

He also got to know the Orok settlements located on the other side of Tarayka Lake.

See: Activities/Ethnography/Orok People – “Shy as Ravens”

See: Activities/Ethnography/Hunting for Eagles from a Dugout