Ethnography

Nivkh People

Activities

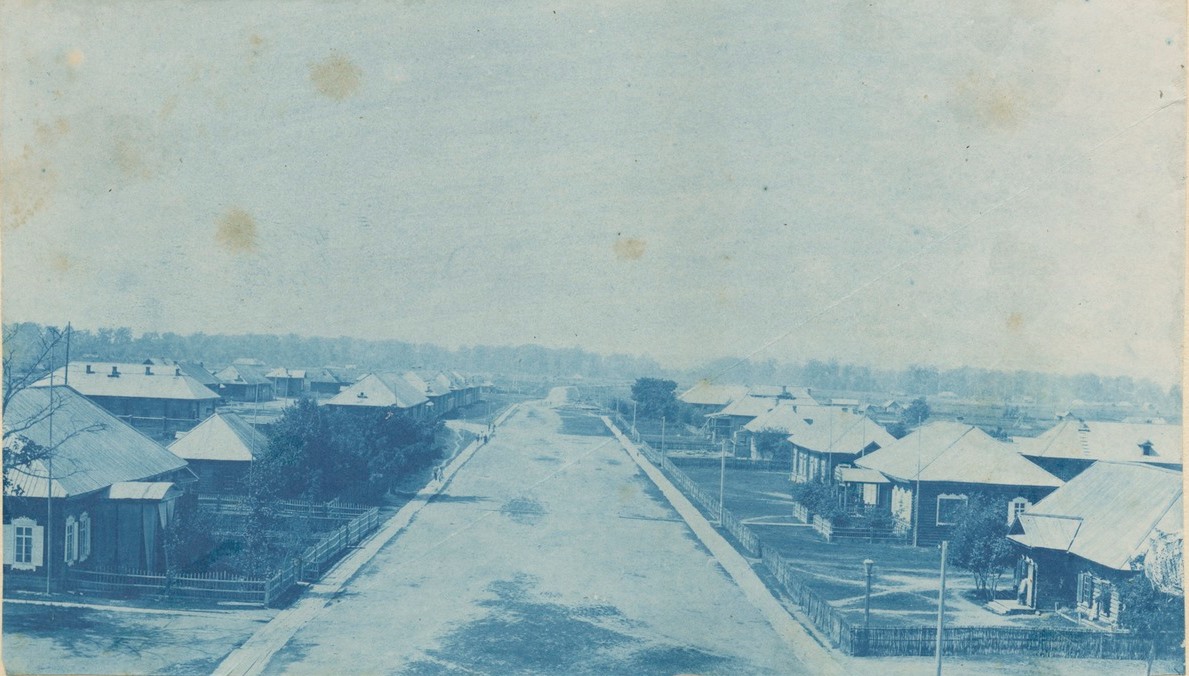

In Sakhalin, Bronisław Piłsudski became naturally interested in the indigenous inhabitants of the island, but soon observing their lives and customs, learning their language, considering how to help those peoples condemned to subjugation in the process of colonization, and how to reduce the burden placed on their lives by ruthless political processes, became his passion. It happened that during the time he spent in Sakhalin, Russia and to a lesser extent in Japan, Piłsudski began to place greater importance on getting to know these people and putting them on some sort of colonization program.

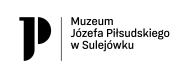

Even at the site of Piłsudski’s first incarceration in the penal colony in Rykovskiy (sometimes called Rykovskoye), located a dozen kilometers from the port of Alexandrovsk, there were settlements of the Nivkh people, more commonly known by the then widespread name Gilyaks. Piłsudski met them during his usual work in Rykovskiy; they assisted in administrative activities: guides, interpreters, rowers, and fish deliverers.

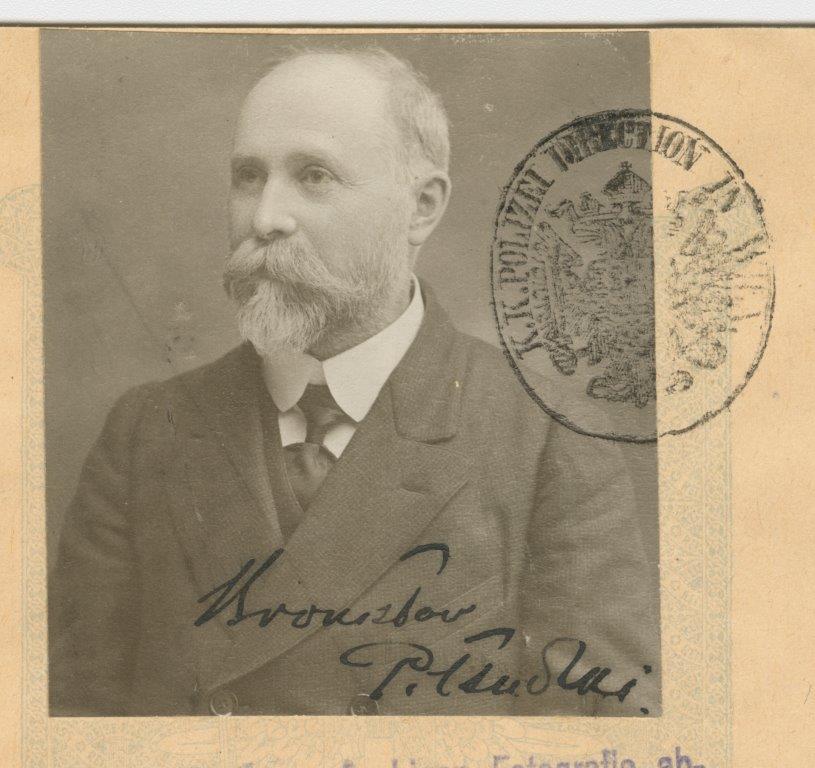

Photo from “Bronisław Piłsudski’s Album Containing Photographs of Sakhalin” in the collection of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences

During his first year in Rykovskiy, Piłsudski was employed first in a carpentry workshop and then, starting in the spring of 1889, in the prison office. At the same time, from 1888, he gave lessons to the children of Russian settlers and officials.

Meeting the Nivkhs on a daily basis, Piłsudski had conversations with them and slowly learned their language. The Nivkh language is considered extremely difficult and it is quite possible that learning it was easier for Piłsudski due to his contacts with the Lithuanian language in his youth in Zułów. His remarkable ease of making contact, gentle nature, and simplicity of demeanor made the Nivkh people eager to approach him.

In 1890, fate brought to Rykovskiy another exile, Lev Yakovlevich Sternberg, a Narodnik who, like Piłsudski, but with greater vigor, conducted his own ethnographic research. Influenced by meetings and conversations with Sternberg, Piłsudski began to systematically collect language materials and objects to carefully note utterances, record songs, stories, and comments on customs.

The result of several years of systematic work is a unique record of the Nivkh people’s “orature” (oral tradition) and customs.

Thinking with great compassion about the future of this minority and relating its fate to that of other minorities oppressed under the system of imperial Russia, Piłsudski summed up his remarks in an excellent and carefully researched article “Position and Needs of the Gilyak People in Sakhalin” published in 1898. The article paved the way for Piłsudski to continue his research and influenced the decision to grant him the position of the curator at the Vladivostok Museum and the secretary of the Vladivostok branch of the prestigious and thriving Russian Geographical Society.

In 1899, he became the curator of the Vladivostok Museum while serving as the secretary of the Vladivostok branch of the Russian Geographical Society. The permanent employment allowed B. Piłsudski to systematize the materials collected years ago, fill in the gaps, and carry out more in-depth ethnographic studies. In 1903, together with W. Sieroszewski, he traveled to the island of Hokkaido in order to conduct linguistic and ethnographic studies of the Ainu people living there.

However, after arriving in Poland in 1906, B. Piłsudski was unable to return to Vilnius, to Zułów in the Święciany district. He stayed in Kraków with the idea that he would be able to elaborate his ethnographic materials there. But he miscalculated. Throughout the period he spent in Kraków, he was unable to find permanent employment. However, despite his financial problems, B. Piłsudski did not neglect his interest in ethnography. While in Podhale, he conducted ethnographic research and in 1911, established an ethnographic of the Tatra Society in Zakopane.

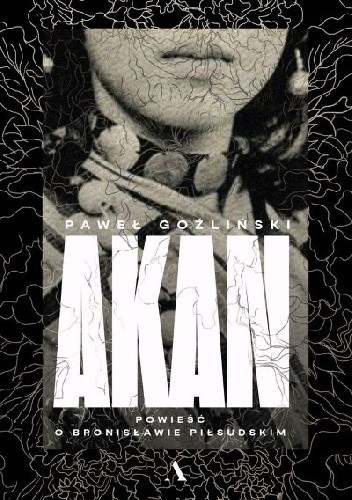

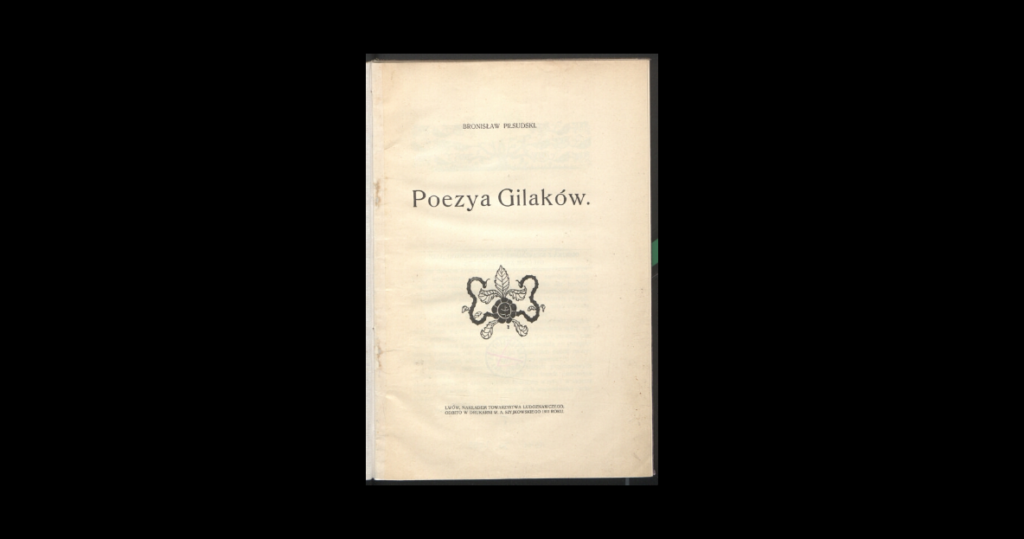

See: POLONA Bronisław Piłsudski Gilyaks’ Poetry

See: Activities/Muzealnictwo/Zakopane

During this period he met Juliusz Zborowski who many years later would describe him in “Ziemia” (1934, no. 1-4, p. 1) as “a lover of Podhale, prowling in and around Nowy Targ.” Living alternately in Kraków and Zakopane, Piłsudski worked on his Sakhalin collections. With a significant help of linguist Jan Rozwadowski, he prepared for publication a work on Ainu folklore and language titled “Materials for the Study of the Ainu Language and Folk-Lore”, Kraków 1912, which is to this day the basic publication in this field. He also printed a couple of articles in the ethnographic journal “Lud” under the title “Shamanism Among the Natives of Sakhalin”, “Lud”, 1909, vol. 14, pp. 261-274, and ibid. 1910, vol. 16, pp. 117-132; Gilyaks’ Poetry, ibid. 1911, vol. 17, pp. 95-12:3; and “Leprosy among the Gilyak and Ainu People”, ibid. 1912, vol. 18, pp. 79-91.

The results of B. Piłsudski’s research work gave him wide publicity among ethnographers in Poland and abroad. Unfortunately, the fact that Piłsudski had never graduated from a university was the main obstacle preventing him from being hired at the university in Kraków. During the First World War, he left Poland and stayed first in Switzerland and then in Paris, where he died a tragic death in 1918.

The printed work of B. Piłsudski is not extensive, but what he had written is undoubtedly of significant value in the literature of the subject. His work on the bear cult is cited by the researcher of this problem, A.F. Anisimo (1950, pp. 309, 313-314, 318), and his work on the native people of Sakhalin – by M.G. Levin, (1958, pp. 123-124). When looking at B. Piłsudski’s research, we must always keep in mind that his published works are only a part of the extensive materials collected on Sakhalin and Hokkaido. In addition to ethnographic materials, he also collected texts of old tales, fables, and songs, which are of great importance to folklore studies. Part of these collections on the language and folklore of the Nivkh (Gilyak) people B. Piłsudski gave to L. Sternberg, a Russian exile and his friend, with whom Piłsudski studied the culture of this people together.

Four Gilyak poems recorded by B. Piłsudski were included in the collection of L. Sternberg titled “Materials from the Study of the Gilyak’s Language and Folklore,” published in St. Petersburg in 1908, with the origin of those records mentioned by the author only in the preface. Some of the materials collected by B. Piłsudski remained in manuscript and were kept in the Archives of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, in the group fond 282, under no. 142 as Piłsudski B. and Sternberg L. Gilyats’ Texts (I. S. Vdovin, 1954, p. 163; R. Jakobson, G. Hüttl-Worth, J. F. Beebe, 1957, p. 100).

Phonograph cylinders with songs of the Ainu people, which B. Piłsudski brought to Poland, have had a separate history. Considered lost for some time, they were found, as described by Jerzy Bańczerowski in his article “Ainu Phonographic Records,” “Biuletyn Fonograficzny”, 1964, VI, pp. 91-96.

Staying among the natives of Sakhalin, this remarkable Pole tried to improve their living conditions, demanded respect for their culture, and fought against bribery of Russian officials. A short text has been preserve in his loose notes that reflects his immensely positive and compassionate attitude toward the local population.