Activities

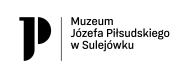

Bronisław Piłsudski and Great Politics

Activities

Although Bronisław Piłsudski is not a figure associated with great politics, it influenced his fate time after time. From the very beginning, it had an impact on his family. If not the consequences of the January Uprising defeat, fewer people directly affected by penal sanctions would have been in his immediate environment; and probably there would never have occurred such a rapid impoverishment of the entire landed gentry in the Polish territories under the Russian partition. The youth self-education associations and organizations, so popular in nineteenth-century Europe, would not have acquired a political and social character, and they wouldn’t have to resist Russification as their main goal. The patriotic education at home would have less significance, and studying romantic literature wouldn’t have been illegal. If Lithuanian youth wanted to obtain university education, they wouldn’t have to go to St. Petersburg; the University of Vilnius wouldn’t have been abolished. The activity of the Spójnia Self-Education Club in the junior high school wouldn’t have to be secret.

Meanwhile, having just started his law studies in St. Petersburg in the autumn of 1886, Bronisław unconsciously got involved in preparations for the assassination attempt on the tsar, planned for the winter, and found himself in the dock, accused of high treason. Unaware of serious consequences of fulfilling the request for help in obtaining chemicals and money, he found himself among the most serious defendants. The death sentence commuted to a long-term penal servitude was just a consequence of the entanglement of the whole environment of patriotic Polish youth from Lithuania in revolutionary movements aiming at the overthrow of the Russian totalitarian power.

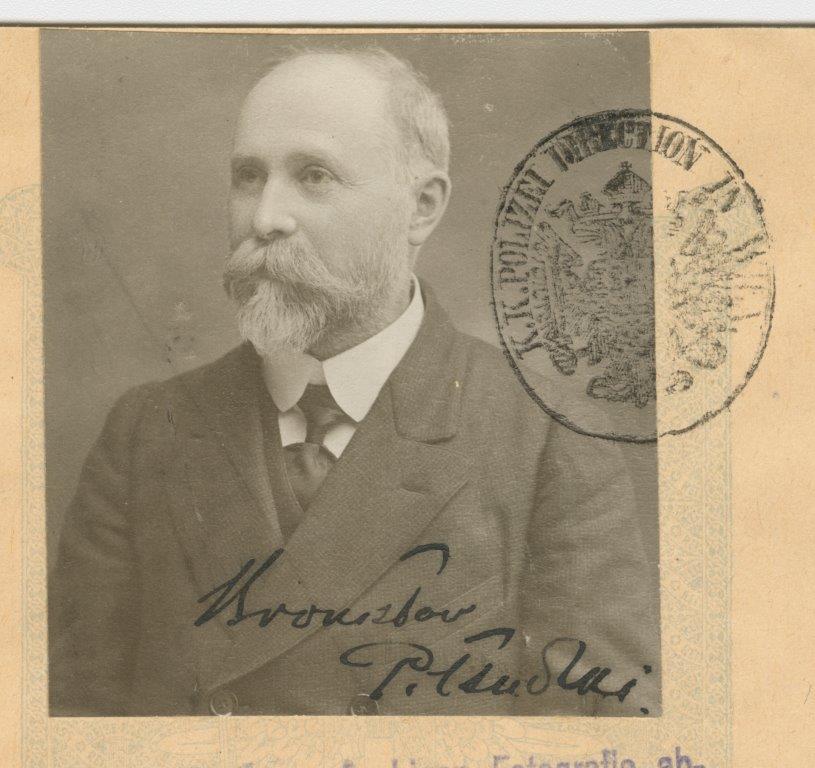

Regardless the main focus on Bronisław Piłsudski’s scientific achievements in the field of ethnology, ethnography, natural science, research of the peoples of the Far East, as well as Tatra Mountains and Podhale in Poland, his activities in the wide political context of the circles he functioned and lived in cannot be forgotten. Before Bronisław Piłsudski reached Poland after leaving Russia, Japan and the USA, all his contacts were made within the socialist environment, so his collaborators of the Russian socialists and his brother Józef Piłsudski helped him during his journey.

However, in the last stage of his life, great politics, worldview frictions, and disputes among Poles, highly burdened him mentally. During the peak of events of 1918, in the last year of the First World War, Bronisław Piłsudski was drawn into the swirl of diplomacy and propaganda around the so-called “Polish issue.” The place of the confrontation was Switzerland and then Paris, the capital of France.

At the moment of the First World War outbreak, Piłsudski stayed in Kraków. In November 1914, he left for Vienna, and in March of the following year, he travelled to Switzerland with the long-awaited Austrian passport in his hand. It seems that he intended to finish his studies in Fribourg, interrupted by a brutal exile to Sakhalin. Meanwhile, his emigration life dragged him into the traditional “Polish hell.” The groups of Poles from Vienna, Lausanne and Paris, fighting against each other, created all too many problems, stealing his precious time. Bronisław was hoping to unite these groups in their joint work on the Polish Encyclopedia published in foreign languages for the “use of European politicians and diplomats.” Being “a forge of noble ideas”, as his friends called him, Piłsudski remained lonely in his naivety. He did not have enough strength to put into practice his ideas, so he turned to different people to deal with them. He became a part of the Sienkiewicz Committee for Aid to War Victims, but founded a “stricter” committee to help Lithuania. He also engaged Lithuanian people from Fribourg, as he gained their great respect. He was looking for reconciliation in this field. He managed to collect money through the Committee for Aid to Poles Working Scientifically, who lived in poverty as a result of the war. These were not all the ideas initiated by Bronisław Piłsudski during his stay in Switzerland. The thought about the others was his constant desire, which gave him no peace.

Piłsudski’s activity during his stay in Switzerland made him physically exhausted and what’s more, it also weakened his mental resilience. Political matters, meetings, deliberations, discussions, and polemics in the press did not create the suitable atmosphere for his personality.

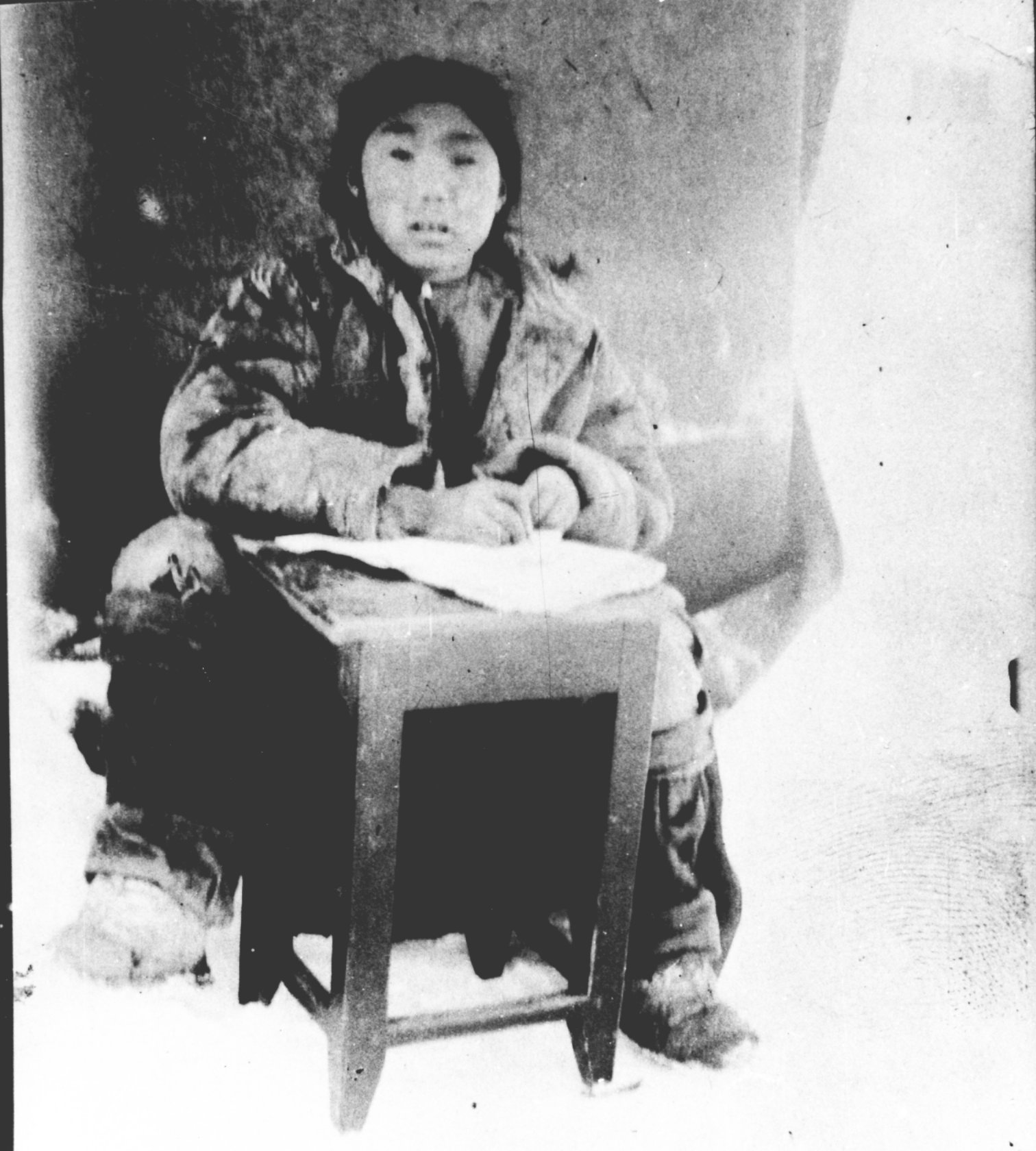

In November 1917, Piłsudski came to Paris and started working as a clerk in the Polish National Committee. He stayed at the official headquarters of the Polish National Committee at 11 Kleber Avenue. He was assigned a modest, but important task, for which he was well prepared. The idea was to create a library of various works collected in foreign libraries, concerning especially ”cartography, population statistics, history, and Polish ethnography.” This gave him an opportunity to visit not only Parisian libraries and museums. He worked in the Department of Relations with the Country and the Bureau of Political Studies and Publications headed by Jan Rozwadowski. As an experienced politician and a father of a big family, he was not only a boss to him, but also a friend and confidant in many issues, both in professional, and personal dimension.

Collecting materials and sources did not consume all of his time. He also had many opportunities for conceptual works. One of them was the idea of establishing a Polish-French publishing company which was to ’’familiarize allies with Polish relations, history, ethnography and culture.” Unfortunately, it emerged at the beginning of May 1918, when Piłsudski struggled with health crisis and disappointment with the rapidly unfolding political events.

The first worrying signs of Bronisław’s health issues appeared earlier, in his letter of 12 April 1918 to Jan Rozwadowski. Among Rozwadowski’s manuscripts, the last letters, notes, and sketches of drawings that Piłsudski addressed to him as the head of the Commission have been preserved in the Ossolineum. According to the letter mentioned above, his responsibilities included drawing up protocols of the Commission’s meetings which he gave the final shape, delegating tasks to his co-workers, estimating the working time for their implementation, and the value of the money earned. What’s more, as an official of the Committee, he was designated for further new tasks, although he did not always actually participate in them. However, the very fact that the leadership of the Polish National Committee sometimes used his name to give credibility to their undertakings was enough for him to feel responsible for them. In consequence, in March 1918, Piłsudski’s name appeared among many other candidates for the Office of Polish Civil Affairs, both for the general commission and for passports and legal guardianship, as well as prisoners of war and internees. In fact, however, he did not participate in this commission.

On 3 May 1918, Bronisław Piłsudski made a plea in which he called on conflicted Polish factions to reconcile on the occasion of the Constitution of 3 May Anniversary and proposed the creation of the League of Understanding. It was his last deed, kind of a testament. He personally distributed the appeal to his friends, but it was not well received.

Rozwadowski’s surviving notes confirm that on 15 May 1918, he received information that Piłsudski was seriously ill, had a persecutory delusions, and should be seen by a doctor as soon as possible. Bronisław was afraid that someone would poison or kill him. The next day, on 16 May, he went to see neurologist Józef Babiński, but returned home very tired. And it was then that Rozwadowski saw him for the last time. In the description of the Piłsudski’s medical condition, Babiński wrote, ”He has arterial hypertension, melancholic depression with a tendency to suicide that is difficult to overcome.”

The up-to date version of Piłsudski’s tragic death is not really controversial. On 17 May, he went to the Saint Michel Boulevard, where his friend Dionizy Zaleski lived, but he did not find him at home. He left a note that reads, ”I came here to ask for injections and end the world. I am innocent in the face of these suspicions that are piling up around me.” According to the relation of the guard of the Pont des Artes bridge over the Seine River, around noon, Piłsudski took off his coat on the bridge, threw it into the river, and then jumped in.

According to the obituary of the Polish National Committee, the funeral service was to be held in the main French church, the Notre Dame Cathedral, but it was suddenly cancelled, and Piłsudski’s body was taken to the Polish Cemetery in Montmorency near Paris. Józef Talko-Hryniewicz recalled him as follows:

”Anyone who have known Bronisław more intimately, could declare that it was nothing about revolutionary or aspiration to social upheavals in his personality. On the contrary, he avoided and disliked politics, and was a gentle, soft, tender and kind-hearted man with almost feminine character. He was always of good cheer, full of fantasy and projects. He especially liked to organize and create things, but didn’t like and want to lead the thing he had started and to work systematically. He lacked the perseverance to do so. He was tired of routine, as well as staying in one place.”

Based on:

Bronisław Pasierb, Bronisław Piłsudski(1866-1918) – Meeting with Great Politics; ”Polityka i społeczeństwo” [Politics and Society] 8/2011, pp. 257-268.

Helena Florkowska-Franćić, The Last Years of Bronisław Piłsudski 1915-1918 (Switzerland – Paris); [in:] Bronisław Piłsudski (1866–1918). Man – Scholar – Patriot; Zakopane 2003, pp. 185-210.

Kazuhiko Sawada, The Story of Bronisław Piłsudski. A Pole Called the King of the Ainu;Sulejówek 2021.