Big Politics

Among Poles in Paris

Activities

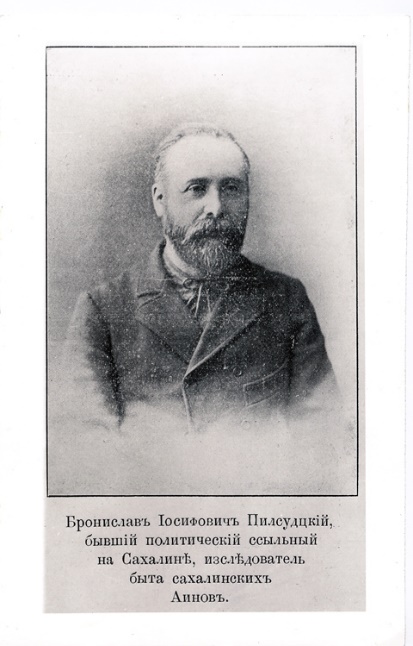

Bronisław Piłsudski had little understanding of the political nuances that pervaded the milieu of émigré politicians residing in Switzerland. When the Polish National Committee, which included people from his entourage, was formed in Lausanne on 15 August 1917, he joined them believing that he was serving a good cause. The Entente powers recognized that body as the only representative of Polish political aspirations and its members later signed the Treaty of Versailles as representatives of Poland. The Committee was chaired by Józef Piłsudski’s opponent – Roman Dmowski.

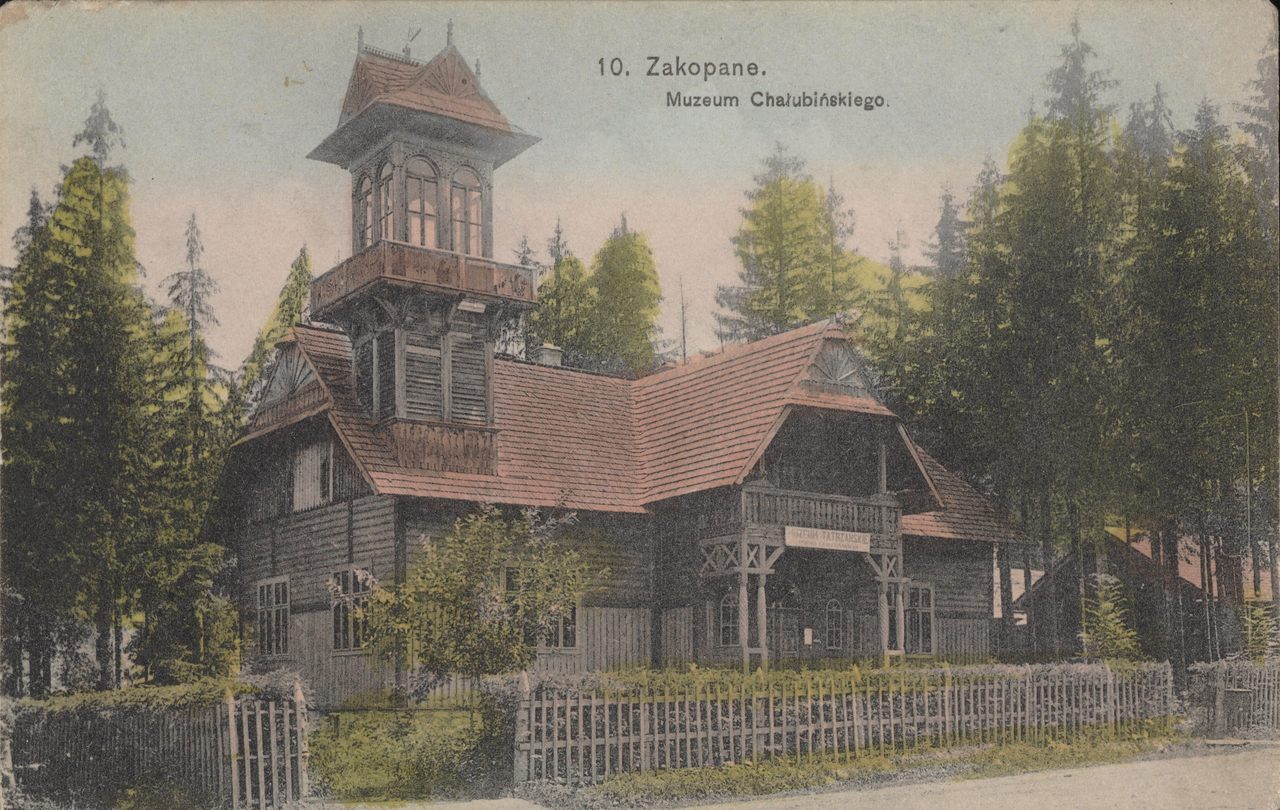

In November 1917, Bronisław Piłsudski arrived in Paris and took a job at the Committee’s office. He stayed at the official seat of the Committee at Avenue Kleber 11 bis. At that time, his material situation became fairly stable, as he had a steady income. Bronisław’s work was related to information in the broad sense – it involved collecting literature on Polish topics, compiling reports, and distributing funds for propaganda. In particular, he devoted a lot of time to editorial work. His responsibilities also included contacts with French politicians, journalists, and academics. The circle of his acquaintances expanded to Poles staying in Paris. He also met friendly members of the Zamoyski family whom he knew from Zakopane.

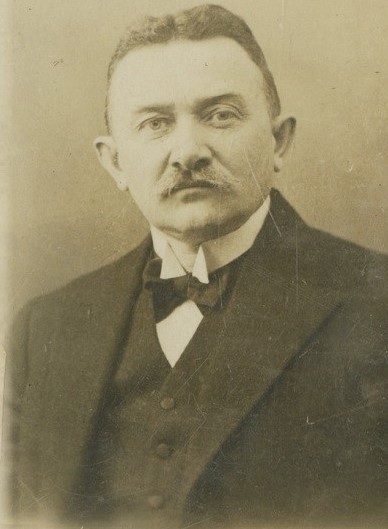

He was assigned to the science department named the Department of Political Studies, Publishing Houses and Propaganda, headed by an economist Jan Emanuel Rozwadowski, a Doctor of Law and Associate Professor at the Lviv University. He was the brother of the Jagiellonian University, Professor Jan Michał Rozwadowski, thanks to whom the ethnographer published his work on the Ainu people in Kraków. Like Bronisław, Jan Emanuel fled from Galicia to Switzerland during the war, and from there he moved to Paris. For Bronisław, this experienced politician and respected father of a large family was not only his boss, but also a friend and confidant in many matters, including personal ones.

Sitting from the left: Maurycy Zamoyski, Roman Dmowski, Erazm Piltz; standing: Stanisław Kozicki, Jan Emanuel Rozwadowski, Konstanty Skirmunt, Franciszek Fronczak, Władysław Sobański, Marian Seyda, Józef Wielowieyski

Jan Rozwadowski’s manuscripts, preserved at the Ossolineum Institute, include the last letters, notes, and sketches that Piłsudski sent or gave to him as the head of the Commission. They shed some light on the circumstances of Bronisław Piłsudski’s death, and show worrying signs that something wrong was happening with Piłsudski’s health. His mood ranged from euphoria to prolonged apathy. The correspondence reveals that he was not kept informed of many decisions. Designated for successive new tasks, he did not always actually participate in the work. The fact that the Committee’s leadership sometimes used his name to lend credibility to some of its actions was enough to make him feel responsible for them. Thus, in March 1918, Piłsudski’s name appeared among those of other candidates for the Polish Office of Civil Affairs, both for the general commission, and for passports, and for legal guardianship, as well as for prisoners of war and internees. However, he actually did not participate in the work of the commission, although it started working on May 8, 1918.

Bronisław Piłsudski witnessed numerous arguments among Polish émigrés. He sought to reconcile the feuding parties, and called for national harmony by fostering favorable conditions for it. He was an ardent advocate of alliance between France and the newly independent Poland, firmly believing in the sense of such a political arrangement. He supported the idea of establishing a Polish-French publishing company that would “acquaint allies with Polish relations, and the Polish history, ethnography and culture.” Unfortunately, the idea emerged in early May 1918, which was a time of Piłsudski’s deteriorating health and disillusionment caused by the rapidly unfolding political events, so it could not be brought to fruition. At the same time, he had a vision of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, intended to be a contemporary continuation of the Polish-Lithuanian Union of the early 15th century, but the political events unfolding on the eastern front increasingly weakened his faith in such a possibility. At the same time, he was concerned about the problems associated with the resurgence of national life in Poland once it would regain independence. However, he was bitter because of not being able to break through with these ideas to influential political groups, although he constantly solicited contacts with such people.

He dreamed of uniting Poles abroad and easing the disputes between the compatriots by an impartial honor tribunal called a Forbearance League. Bronisław expressed this idea in a proclamation that he sent out to prominent figures in the Polish enclave in Paris. This plea, bearing the symbolic date of 3 May, did not find supporters. There was no question of either reconciliation or compromise. The Polish community in Paris was divided into groupings and coteries, which were often in opposition to the Polish National Committee. Bronisław suspected that his last name, Piłsudski, served them only as a label, which he felt as a heavy burden. At the same time, to Commander Józef Piłsudski’s partisans, his brother’s accession to the hotbed of the National Democrats was somewhat of a betrayal.

The trip to Paris deepened Bronisław Piłsudski’s sense of loneliness. In the last days before his death, he complained to Jan Rozwadowski that he strongly felt the need for family life. Another émigré activist and philosopher Wincenty Lutosławski wrote, “Paris tormented him – and there is no doubt that these last six months spent in the bustling capital shortened his life. In Paris he witnessed constant disputes between compatriots, slander, prejudice, and mutual dislike. He addressed people in the name of harmony and good, but in vain; he saw the constant and always irreconcilable differences between them, arising from personal prejudices. He himself had a strange gift for recognizing the best in everyone; he could not comprehend the tendency to emphasize the worst in people. […] His health conditions in Paris were far worse than in Switzerland. He lived in a small room in the attic and was tired of the stairs which he had to climb with difficulty, having a heart disease and lungs at risk. He did not have as much sunshine or as clean air as at Lake Geneva; nor did he have such warm friends, because in Paris everyone was too occupied in his own business, and traveling from one district to another was very difficult. With the very slim salary he received for his work (120 francs per month) and the prices enormously increased by the war, he could not provide himself with the necessary comforts and was very hesitant about going for his treatment. The deterioration in health came suddenly and caused an unexpected death.” It is known from Rozwadowski’s notes that Zamoyski visited Piłsudski on 15 May, and declared that he was completely ill, suffering from mania of persecution, and should be seen by a doctor as soon as possible. Bronisław was afraid that someone would poison or kill him. After Piłsudski’s visit to a doctor, the recommended neurologist Józef Babiński wrote, “He has high blood pressure, melancholic depression with a suicidal tendency that is difficult to overcome.”

There are no controversies related to the current version of Bronisław Piłsudski’s tragic death. On 17 May 1918, he drowned in the Seine River. It was a suicide associated with his depression. Twelve days later, funeral services were held at the Les Champeaux Cemetery in Montmorency near Paris. Bronisław Piłsudski’s grave is still there today.

In the first half of July 1919, Poland’s Head of State Józef Piłsudski was in Wielkopolska, dealing with military matters of the General Districts of Poznań and Pomorze. At the time, he visited the Zamoyski family’s residence in Kórnik near Poznań to personally decorate 90-year-old Jadwiga Zamoyska with the Order of Polonia Restituta. At the time, he also thanked her son, Count Władysław Zamoyski for taking care of his brother Bronisław in Paris.

Based on:

Jerzy Chociłowski, Bronisław Piłsudski’s Duel with Fate, Warszawa 2018

Antoni Kuczyński, “Bronisław Piłsudski (1866-1918), an Exile and Researcher of the Culture of Peoples of the Far East,” “Niepodległość i Pamięć”, 22/2 (50), 7-93, 2015

Bronisław Pasierb, “Bronisław Piłsudski (1866-1918) – Encounter with Great Politics,” “Polityka i Społeczeństwo”, 8/2011

Kazuhiko Sawada, A Story of Bronisław Piłsudski. A Pole Named King of the Ainu People, Sulejówek 2021