Social Relations

Japanese Specialists in Russian Studies – Socialist and Orthodox Clergy

Activities

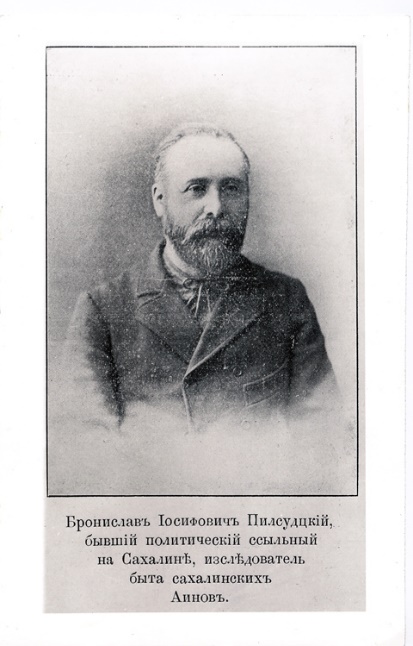

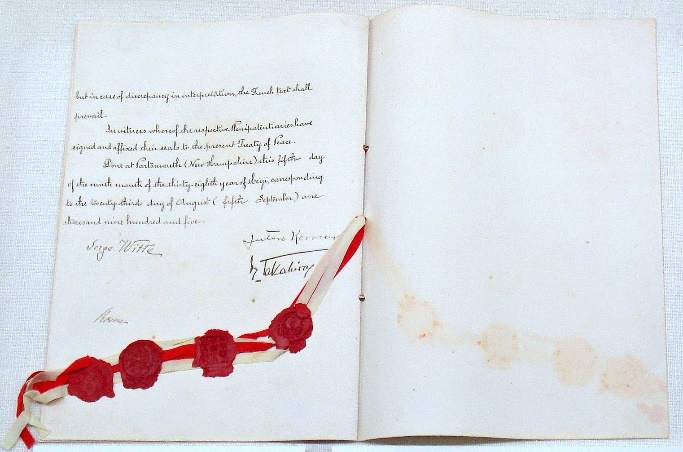

From the very beginning of his stay in Japan in 1906, Piłsudski met with Japanese translators and interpreters from Russian, who were a serious resource for the revolutionary Russian émigré movement. The Japanese language was not completely foreign to him, as many of the Ainus living in southern Sakhalin spoke it and during his expedition with Sieroszewski to Hokkaido three years earlier, they were assisted by Sentoku Tarōji, a person of Ainu-Japanese descent, and they used a small Ainu-Russian and Japanese-Russian dictionary. Although accustomed to the language, Piłsudski did not master it, as he was not planning to stay in Japan for a long time, and used the help of interpreters.

Piłsudski met some “professional” interpreters in Tokyo. The first was Matsuda Mamoru, in whose house Piłsudski stayed. Soon after, he contacted Prof. Suzuki Otohei from the Russian Studies Department of the excellent Tokyo University of Foreign Studies (TUFS, which, by the way, is the only University in Japan that currently has a Polish Studies Department); Otohei recommended his student Shimada Masaharu to assist him in moving around and arranging things in Tokyo. Piłsudski also contacted Ōi Masahara, a former law student in Russia and a translator from Russian who helped with communication at the prisoner-of-war [POW] camps in Himeji in western Japan. This contact, as well as other meetings with interpreters at POW camps, might have been the source of information about Roman Dmowski and Józef Pilsudski’s visit to Japan a year earlier. This is not absolutely certain, but it is an interesting trail to consider.

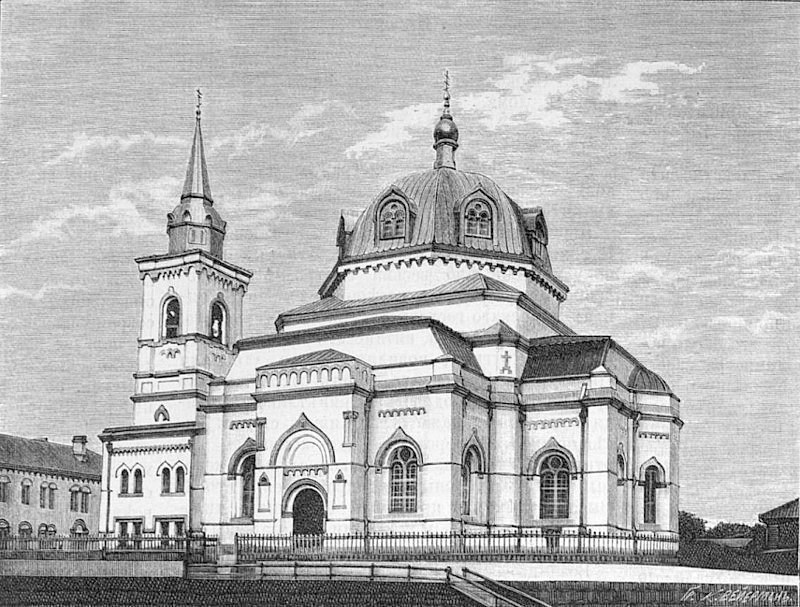

Some of the Japanese interpreters employed temporarily at the POW camps came from groups associated with the seminary at the Russian Orthodox Church in Tokyo, which at that time was headed by the charismatic Bishop Nikolai Kasatkin, later recognized as a saint and sometimes called the Apostle of Japan. Like many Russians, he also began his mission in the country from Hakodate, where he was sent as a chaplain of the Russian consulate. After relocating to Tokyo, as an archimandrite bishop, he built a beautiful Byzantine-style Holy Resurrection Cathedral in the center of Tokyo, along with a seminary. The cathedral was built under the supervision of the prominent English architect, Josiah Conder.

Bishop Nikolai translated the Scriptures and some liturgical texts into Japanese, and encouraged seminary students to continue their translation work. Most of the interpreters and translators who collaborated with Piłsudski came from that group.

All three translators involved in helping Russian socialists at the time, Susumi Ueda, Yoshio Gunji, and Makio Takai, were students at the mentioned above seminary. Since each of them also participated in conversations with Russian prisoners of war in various camps located in several cities of western Japan, Piłsudski was certainly able to learn about the situation, as well as the views and morale of the prisoners, especially Poles. The three translators collaborated with “Volya”, the periodical of the “Nagasaki group”; they also helped with contacts with Japanese socialists grouped around the “Hikari” (Light) periodical. An important point is that socialism grew in Japan on the subsoil of the Christian worldview and around missionaries, both Protestant and Orthodox.

In fact, Piłsudski kept in touch for longer with some of them, for example with Gunji who translated for him an excerpt from Ryūnosuke Okamoto’s “Japanese-Russian Negotiations in Hokkaido”, which Piłsudski needed in 1908 to write a text on the aboriginal peoples of Sakhalin; it was published in Russian and German in 1909.

The second of the three translators, Susumi Ueda, worked as a professional translator and after graduating from the school at the Cathedral where he was baptized as Matvey, he even published a Russian-Japanese phrasebook. Piłsudski met him in late January 1906, and in March he wrote in a letter to the editorial office of “Volya” that Ueda was waiting to be paid for the materials he had sent. Ueda knew many people connected with the Orthodox Church in Tokyo, Russian emigrants and Chinese activists. Ueda’s postcard sent to Piłsudski in 1907 has been preserved, in which Ueda conveyed the latest news from Tokyo, including the fact that Bronisław was often mentioned at the Hakodate House. In another card from 1907, Ueda wrote that he had received a letter from Bronisław, that another mutual Russian friend (Podpakh) lived with his family in Tokyo, and that he had sent copies of “The Japan Times” and socialist newspapers to Piłsudski’s place of residence in Kraków.

Thanks to his cooperation with Ueda, Piłsudski managed to publish in Japan’s “Sekai” (World) magazine his first scientific work outside Russia, a two-part article on the Ainu people and their situation, illustrated with photographs taken on Sakhalin. The editors were interested in news about Sakhalin, the southern part of which had been under Japanese administration for a year. Piłsudski also corresponded with Ueda later, after he left Japan.