Activities

Modern Museology

Activities

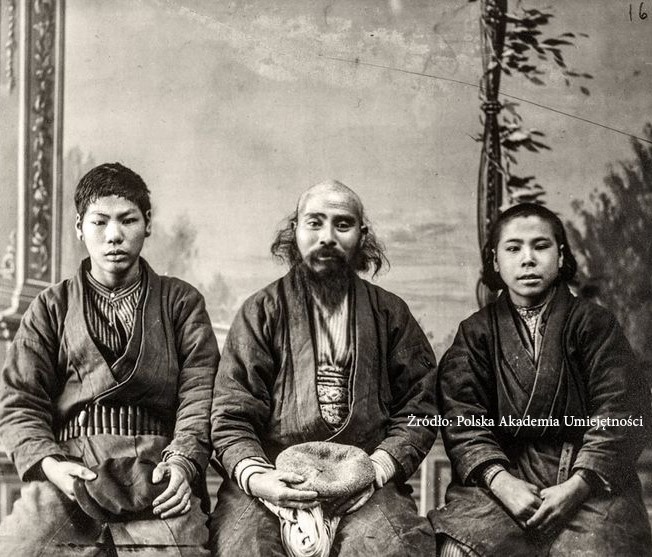

“In the past, I used to be a curator of the large Museum in Vladivostok for three years; I visited numerous museums in different countries like Japan, America, England, France, Germany, and Austria, and this year, having already in view our Tatra Museum, I tried to get to know more carefully the museums in Prague, Switzerland and Belgium. I have also read a number of special books, articles and reports on museology,” has written Bronisław Piłsudski in the article about “tasks and methods of running the ethnological department” at the Tatra Museum.

From the beginning of 1913, Bronisław Piłsudski stayed in the small town of Neuchâtel in the western part of Switzerland with 20,000 inhabitants. The reason why he chose this place is unknown, but he possibly was invited by the French cultural anthropologist, professor of the University of Neuchâtel, Arnold von Jenepp, whom Piłsudski probably met in Paris four years earlier. Bronisław attended lectures at the University of Neuchâtel as an auditor. Because he stayed there for a short time, his goal wasn’t to obtain an academic degree, but rather to eagerly learn museology with a view to the Tatra Museum. In one of his letters to Bronisława Giżycka, the treasurer and the person who replaced him in his absence as the President of the Ethnological Department of the Tatra Society, he wrote:

“The photos of the objects in the Museum are very valuable. Now, every Museum takes photographs of each item, attaching things to the description. We will also need to make catalogs of exhibits on paper, since not having them, our collections have no scientific value. It will be necessary to choose one pattern, print the cards (in case of any questions) and then fill up as much as possible. Together with the photos, it will be a beautiful work for the illustrated catalogue. I assume the negatives remain in the Museum. Then the exchange of photos with other Museums will be possible. This was much desired in Prague and in Basel in Switzerland. If you would like to start on describing straight away, I can send you samples of cards – catalogues of some Museums.”

The first catalogue of the Tatra Museum ethnographic collections was designed earlier in 1907 on the initiative of the Tatra Museum Society. It was designed by Kazimierz Brzozowski and published by the Tatra Museum. Five years later, Piłsudski got the museum collections of the time organized, put temporary numbering and entered new assets into the inventory book. He believed the inventory of the collection should be carried out according to specific principles that he presented in the following year in his memorial On the Tatra Museum (On the Arrangement of the Ethnological Department, “Rocznik Podhalański” (Podhalański Yearbook) [1]: 1914-1921, pp. 147-188). There, he made the classification of museums:

“In the past, ethnographic museums presented collections of exhibits that were more or less organized, more valuable or just collected by accident, or donated, and their purpose modeled on the painting galleries was to make impressions, and to arouse curiosity and interest. Currently, museology has become more mature, and sets broader and much extensive goals. Ethnographic museum and museums of comparative ethnography (in German: Voelkerkunde) seek to collect materials and exhibit them in such a way as to give the opportunity to learn about human and the peoples of the world in general, classifying exhibits by the geographical or comparative-developmental principle. National museums (in German: Museums der Volkskunde) try to give the life expression of the ancient and contemporary era of one nation. Finally, provincial museums (the French call them musees canionaita), comprised of ethnological, historical and nature departments, except for presenting distinctiveness of their region culture, serve also as centers of research work in their provinces. At the same time they are institutions spreading knowledge, education, and social advantages. For adults, they are what school collections or object lessons are for children.”

So, the museums were not only meant to provide impressions, but also educate. In his letters to Giżycka, Bronisław suggested the operational system which today we would call promotional. It was not much different from the contemporary modus operandi of such institutions that allow simultaneously expand exhibit collections and build relationships with the local community. He wrote:

“I suggest finding ways to interest a wider audience in our work. My conclusion is the following: In May, or in June at the latest, we should announce a contest to select best: 1. photographs and drawings related to Podhale (Spiż and Orawa); 2. items used in the Podhale life. Next, at the end of the summer holidays, that is 15 July – 1 August (or other most appropriate date), we would hold the exhibition of these items and offer 3-5 rewards for each department. Priority in the photograph context would be given to those who provided a series of photos, e.g. a series of buildings in various villages of Podhale, Spiż, or Orawa, a series relating interiors or types of the oldest people, a series connected with celebrations (e.g. „joyful events”, weddings), working in fields, domestic manufacturing or a series showing one particular locality, etc. As for the drawings, maybe Mr. Brzega will give some thoughts; maybe a series of beams, a series of inscriptions on old houses, etc. Priority would be given to photos that include as accurate description as possible. As for the items, priority for the reward would be granted to the inhabitants of Podhale and the local population in general, as well as to those who will present for competitions and exhibitions items that are not in the Museum yet. Also to those who will provide detailed descriptions related to the origin, the manner of use, and the customs associated with the item. The first announcement about rewards could be mentioned in general terms, and simultaneously it’s necessary to appeal to people of goodwill for donating money, and to appropriate publishers for prizes. For example, we could ask the Sightseeing Society in Warszawa for a few examples of the “Ziemia” [The Earth] Annual, the Dzieduszycki Museum for some Hutsuls, and the Ethnological Society in Lwów for a few volumes of publications. Perhaps the Society of Science in Poznań could give a little or the Chałubiński Museum, and maybe our Department… The goal will be achieved when only the youth is liven up and is given the purposeful work during their holidays, and the Museum will have a lot of items to buy or get acquainted with, or take photographs of them. Afterwards, it will be possible to ask the owners for the exhibited photographs, and create an album, what would be very helpful while publishing. The exhibition organized time after time, will inspire to work and help to make relationships with people we do not know yet. Farmers may also bring out their old things to display and receive a reward.”

Elsewhere, he also mentioned that gathering collections should be the leading role of this type of institutions:

“If there are no lectures or talks, then you don’t have to worry about it, because it’s a subordinate thing. The main concern is that some sincerely involved people collect materials, items and find interesting people in different places.”

He also had an idea for promotion:

”This year, it would be good to keep summaries of lectures and talks, if only anyone can get involved in such a task, and earn money by sending them to newspapers, taking their extracts into the documentation of the Department.”

If Bronisław Piłsudski’s copied solutions, as well as his own ideas in the field of museology were supposed to be expressed in contemporary language, it would turn out that he promoted collecting, designing and making the collections available as the main activity of the institution, as well as educating and popularizing as the complementary activity by involving the local community, and publicizing events in the media. In short: a contemporary museum.

Based on:

Małgorzata Kwiecińska, Letters of Bronisława Giżycka and Bronisław Piłsudski concerning The Ethnological Department of the Tatra Society;„Wierchy”, Y. LXXXVII (2021), pp. 173-196.

Bronisław Piłsudski, T. Chałubiński Tatra Museum in Zakopane: Tasks and Methods of Running the Ethnological Department; Kraków 1915.

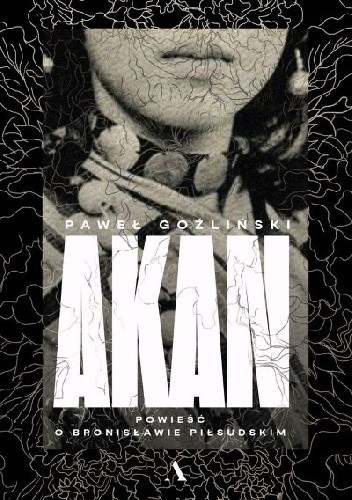

Kazuhiko Sawada, The Story of Bronisław Piłsudski. A Pole Called the King of the Ainu;Sulejówek 2021.