Ethnography

Hunting Eagles from a Dugout

Activities

See: Activities/Ethnography/Orok People – “Shy as Ravens”

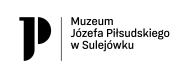

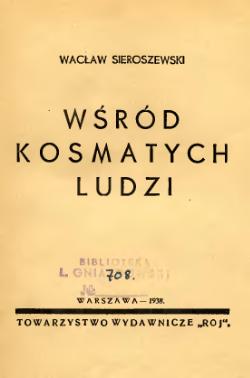

On 1 November 1904, Bronisław Piłsudski set out by boat to Kotankesh and met his acquaintance Sitiriki on the coast. He showed him a very original way to hunt for eagles using abandoned dugouts.

In the following days, Piłsudski observed the autumn seal hunting, but he focused on finding the shaman who was famous in the nearby villages of Furechish, Akara, and Hunup. Being unable to meet him, he went to Motomari where he witnessed the ceremony other than iomante involving the offering of a hunted bear.

On 11 November, Piłsudski was in Seraroko, passed through the familiar village of Otosan that was known to him, and finally arrived in Ai, where his family and relatives – his wife Chūsamma and their son, her uncle Bafunke, and other friends – were waiting for him. For the next few days, he went on the Ai-Otosan-Korsakovo-Seraroko route and managed to see the ceremony of “sending back the soul of the bear” (iomante) for the last time on 28 November in Otosan.

Less than a month later, on 21 December, Piłsudski sent a telegram from Korsakovo to the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg requesting an extension of his research stay on the island for another year. Unfortunately, the fall of Port Arthur on2 January 1905 thwarted his plans: the war took a very unfavorable turn for Russia which lost its entire fleet. As we know, taking advantage of the war, Bronisław’s younger brother Józef went on a secret mission to Tokyo. He was in that city almost exactly when Bronisław greeted his Nivkh friends in the villages in the northern part of Sakhalin. While Bronisław was putting his notes in order in the village of Uskovo two thousand kilometers to the south east, Józef was submitting his memorandum to the Japanese foreign minister, in the Kasumigaseki District of Tokyo…

But let’s go back to Sakhalin. As the situation became more difficult, all scientific research had to be postponed. The Ainus were very much afraid of reprisals from the Russians and their suspiciousness. Arms were in short supply, and food prices were reaching horrendous levels. Piłsudski was preparing to leave Sakhalin, tentatively planning a route through Nikolayevsk and then by rail to the European part of Russia. He was preparing to leave by visiting Siyantsy, Naibuchi – the villages he knew – where he had to close a school; in early March 1905 he came to Ai, where he was setting up his family for the upcoming changes; he intended to return to take his wife to a new place of residence, probably already on the mainland.

Piłsudski slowly moved northward. A shaman in Otosan still performed a farewell and a mantic ceremony for Bronisław… Farther north, a flu outbreak decimated the completely non-immune Ainus, and killed also many Russians. Piłsudski himself fell ill and recovered from the infection very weakened. On 23 March, he rushed on a reindeer sled across the still snowy plain to Onor where he stayed for two weeks. In Onor, he finished the “Draft Principles of the Management of the Ainus of the Sakhalin Island” commissioned by Governor Lapunov.

Later, Piłsudski stayed in the village of Rykovskoye for a month (between 13 April and 12 May); he was writing his reports and compilations – “Some Information on Individual Ainu Settlements on the Sakhalin Island” and a modification of the “Draft Principles of the Preservation of the Customs and Management of the Ainus”, which he had earlier submitted to Governor Lapunov, as well as reports on the reading and writing education implemented in the winter 1904/1905.

Meanwhile, on 30 April, Piłsudski’s sentence formally ended (including obtaining a status of the settler, non-peasant) and he was given the opportunity to settle anywhere in the Russian Empire, excluding the capital; he was also allowed to return to his hometown. To complete the formalities and carry out further preparations, Piłsudski traveled to the village of Derbinskoye (now Tymovskoye) where he finished his work on the description of Sakhalin’s vegetation, then headed to Alexandrovsk – the port where his Sakhalin journey began in 1887.

On 11 June, he left Sakhalin on the ship “Vladivostok” and sailed to Nikolayevsk located at the mouth of the Amur River. He stayed there for 10 days and then sailed to Khabarovsk to visit the village of Mariinskoye and collect information about the Ainus living in the Amur River region.

After a few days, Piłsudski reached Khabarovsk; on 14 July, he closed a report on the current situation among the indigenous population on Sakhalin, which he wrote for the chairman of the Russian Committee for the Study of Central and East Asia, V. Radlov.

In early August, Bronisław Piłsudski was already in Vladivostok, where he gave lectures (on 5 and 12 August) on the results of the research he carried out on Sakhalin as an associate member of the Amur Krai Research Society (OIAK) for the Academy of Sciences and under the auspices of the OIAK.

On 5 September, a peace treaty between Japan and Russia was signed in Portsmouth.

Under this treaty, southern Sakhalin came under Japanese administration, which meant that his family would formally be in the Japanese territory, as the fate of southern Sakhalin; i.e. the territory south of the 50˚parallel was sealed: it was to be under Japanese administration. Thus, Piłsudski probably visited the village of Ai for the last time in mid-September 1905 and met with his family, Chūsamma and Sukezō. Bafunke ultimately refused to let Piłsudski’s wife and their son go, so Bronisław separated from his family.

He set off to return to Europe shortly thereafter. He carried a lot of ethnographic materials with him, which he wanted to present to the scientific community.